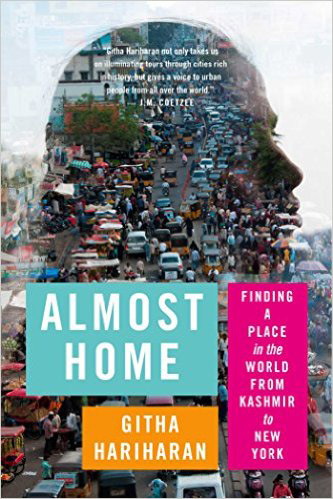

Almost Home

“Stories, like real life, can strip you of the prettier features of illusion.” This is exactly the kind of line that ensures us we are in capable hands with Githa Hariharan, who narrates her travelogue Almost Home: Finding a Place in the World from Kashmir to New York more as a travel guide, less as the star of her own world. To read this book is to venture on a rigorous journey around the globe and through pockets of time. As a fellow travel writer and having also lived a peripatetic life that crosses continents and hemispheres, this is the best travel book I have ever read. “Stories, like real life, can strip you of the prettier features of illusion.” This is exactly the kind of line that ensures us we are in capable hands with Githa Hariharan, who narrates her travelogue Almost Home: Finding a Place in the World from Kashmir to New York more as a travel guide, less as the star of her own world. To read this book is to venture on a rigorous journey around the globe and through pockets of time. As a fellow travel writer and having also lived a peripatetic life that crosses continents and hemispheres, this is the best travel book I have ever read.

Hariharan, who is Indian and currently resides in New Delhi, has lived in many places around the world. She forges the Indian and universal together in instances like this, when trying to explain why she’ll never truly have an answer to that question Where are you from?: “What do you do with a person who can’t decide on her native? What if she is a [ . . . ] person with too many cities in her life, a person burdened by and enriched with too many natives?” Indeed, it may be difficult for a person who asks “where are you from” to comprehend why everywhere is almost home yet nothing is because, having been raised in Manila, Japan, New York, and several cities within India, there is no one particular place she can point to. Periodic interjections of her own experiences form the scaffolding upon which she constructs this book and observations of “elsewhere.”

Almost Home bears no narrative arc. Yet Hariharan’s anthropological curiosity, the sign of a true traveler’s mind, illuminates the tales with a colorful confetti of elements from philosophy and art to literature and history. The results remind me of the best parts of Graham Greene’s oeuvre and Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities (which in fact she pulls her epigraph from).

Selecting just a few examples from this book is difficult because so much of it appeals. I’ll start, though, with a visit to a museum in Córdoba, Spain. Hariharan is wandering in the Jewish quarter, happily lost, when she discovers a fourteenth-century house, now the small museum known as Casa de Sefarad. Here her Calvino inspiration really shines and transports us to a mystical time and place with cinematic ease:

The museum’s interests I found refreshingly different; for once the past was not the same old series of mind-numbing acts of aggression or grandeur. Instead it was about music, poetry, ideas—and in particular as practiced by the women of Andalus.

She goes on to write about rows of women’s right palms in gold and silver and various sizes. Known both as the mano de Fatima and the hand of Miriam, these hands are good luck charms and agents to ward away evil spirits. Learning about these symbolic hands takes us to the days of the Prophet Mohammed, to the Exodus stories of Miriam who saved her brother Moses, and to the use of forward-facing palms as a symbols in multiple major world religions.

We move seamlessly into a captivating tale of Wallada the Umayyad. The daughter of Mohammed the Third, Wallada established a reputable literary salon which, as Hariharan describes, sounds a bit like Gloria Steinem meets the Moulin Rouge. Hariharan so exquisitely steps into Wallada’s ghostly shadow and draws such a vibrant sense of place that was Córdoba, I did not want the story to end.

People and places come alive in this book, not through dusty encyclopedic research, but by Hariharan’s deft incorporation of historical fiction into the essayistic and travelogue elements of her narrative. One prime example of this is in the section about 2012 Algiers, a place celebrating fifty years of independence from France. Here she turns place into character, familiarizing us with Algiers before colonization, during, and after the colonists’ departure. This compels readers to ponder the prevalence of colonization elsewhere in global history and wonder about the experiences of the natives then and even for centuries after.

World travelers and armchair travelers alike will find themselves happily lost and found in this book. It’s worth repeatedly returning to—if only to gather background information when determining where you’ll travel next.