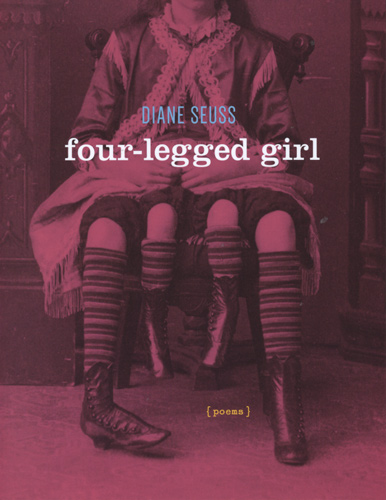

Four-Legged Girl

In Four-Legged Girl, Diane Seuss’s latest book of poems, we move from the rural country of Wolf Lake and into the city, where the speaker shows us her younger self lounging on red velvet sofas, parading in pink leopard print pants, and generally swapping naivety—this is, after all, a book that opens with a jump rope song—for misdeeds, true love or, in a pinch, ecstatic moments. And in the interstices, there is wisdom to be found here as well, the kind of wisdom that one misfit passes along to another. In Four-Legged Girl, Diane Seuss’s latest book of poems, we move from the rural country of Wolf Lake and into the city, where the speaker shows us her younger self lounging on red velvet sofas, parading in pink leopard print pants, and generally swapping naivety—this is, after all, a book that opens with a jump rope song—for misdeeds, true love or, in a pinch, ecstatic moments. And in the interstices, there is wisdom to be found here as well, the kind of wisdom that one misfit passes along to another. “It wasn’t the drunk boys who wanted me,” the speaker admits:

It was the girls. It wasn’t my body they were drawn to,

but my life, the weird underworld I had going for me

This is a speaker with stories of junkies and serial killers and haunted houses, the kinds of stories we’re all secretly dying to hear.

To say I have been eagerly awaiting this book is an understatement. I’ve been looking forward to it since I stumbled across one of Seuss’s poems, “Either everything is sexual or nothing is. Take this flock of poppies,” in Blackbird three years ago. I ordered a copy of Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open—Seuss’s previous Juniper Prize winning title—and happily devoured it the moment it arrived, even though the poem that led me to buy the book wasn’t even in it.

But let’s return for a moment to that jump rope song, the one that opens Four-Legged Girl. It’s a lovely poem, and it makes an apt opening gambit for the book. Because in this world, even the most innocent gestures are opportunities for lurid surprises, and a jump rope song, in Seuss’s hands, is:

Born like milk and dies like butter, like batter after you add the eggs,

those orbs with a beating heart inside, yellow foam

on the lake by the bowling alley, blank pins gone gold,

and the trophy mother won, and her rayon sweater soaked in beer.

Using repetition that doubles back on itself but never grows tiring because the repeated expressions are so short—“dies like butter” is one of them—this first poem is saturated with the same rich imagery and sonic sensibilities that made Wolf Lake such a show-stopper. But as the book progresses, Four-Legged Girl capitalizes on those same strengths to different effect.

Wolf Lake began with the pressurized assertion that “Jesus wept and so did Rowena Lee / and one of the Haven girls but not the other” and keeps building force from there, its long-lined free-verse poems and run-along sentences enacting the explosive fertility and catharsis and catastrophe that both the human body and the living world are capable of. By comparison, Four-Legged Girl is built around gestures, rich rhymes and repetitions and ornate language. It engages with formal constraints purposefully which, rather than imposing order or formality, has the effect of focusing our attention, offering small counterpoints to the effusiveness, the expressiveness of the poems.

It’s also worth noting that from a thematic standpoint, expressiveness sometimes operates as a stand-in for beauty, and at several points in the book, flamboyant articles of clothing become occasions for moving poems. The book treats faked finery and elaborate costuming with seriousness, exploring how costumes can be modes of play, the means for self-discovery, or a strategy for self-defense. Or all of the above—as many misfits already know, a good enough disguise allows the wearer to hide in plain sight.

Also up for discussion is the way urbanity, style, and sexual knowledge conflate and/or clash with love and truthfulness. The speaker admits in this passage from “Warhol’s Shadows” that she is (was):

soft, stupid, not yet muffled by useless wisdom and silly ambitions

which are stand-ins for exhilaration and what is called love, sweet

until it was bitter, and when it was bitter I spat it out

onto the street, which glittered, in winter, with road salt,

fish scales, sequins and spare change.

There is a productive world-weariness here that takes issue with the notion of social class, particularly where it can be misused to excuse away the absence of love, care, or depth.

And then there’s the related question of whether anything is as all-or-nothing as it first seems. How much does what one does relate to who one is? Is life ever truly a yes/no, either/or endeavor? This is a question Seuss raises again and again, through poems constructed around self-contradicting ultimatums and impossible choices. “Either everything is sexual or nothing is,” Seuss insists. “Take this flock of poppies / smoke-green stems brandishing buds the size of green plums, swathed / in a testicular fur.” I love this poem in particular, so so much, because of how it expands through reduction, how it builds a convincing poetic truth out of a preposterous claim. The poem—like much of Seuss’s work—so lavishly captures the contradictions of arousal and sexual propriety.

The speaker in Four-Legged Girl simultaneously has nothing and everything to lose. But a tone shift comes along, too, as the speaker trades innocence and exhilaration for experience and the seemingly requisite heartbreak that comes after. By the book’s fifth sequence the speaker admits “I’m full of sadness”:

As full as a refrigerator on pay day.

My nights are packed with dreams.

Jam-packed as a husband-leaving suitcase.

Although the voice remains as incisive as ever, the language becomes progressively quieter in the fourth and fifth sequences, until we land at the very end in the realm of circus sideshows and aftermaths. We return to a more operatic register, but sadder than before. Now, we see, “Beauty is over”:

Beauty was four movies ago, the one in which Vaseline was smeared

on the lens to fog the stars beautiful. Now the rabbits’ nests are empty,

the dog looking self-satisfied. Feasting on the younger versions of ourselves,

that’s what we do.

If Four-Legged Girl is an extravagant book, it is also a generous, deeply honest one. The speaker treats herself—and by extension, us—with sympathy and judgment in equal measure. Here, love’s effect is almost always disarray, if not complete breakdown. As Seuss tells us, “The only way to know tenderness is to dismantle it.”

If Wolf Lake is a tornado, then Four-Legged Girl is the run-down mansion that has outlasted a tornado or two. We’re left to peer into every closet, run our fingernails along the peeling wallpaper, and the whole thing resonates with the ghosts of needy souls who blew into the foyer before us. None of it feels quite safe. But isn’t that what we came for, what we’ve been wanting all along?