Literal – Spring 2013

Literal sets out to “provide a medium for the critique and diffusion of the Latin American literature and art,” and, at least in this issue, it is heavy on critique. Unlike the majority of literary magazines I am familiar with, most of Literal consists of short critical articles, with subjects ranging from a Picasso exhibit, to Philip Roth’s retirement, to social movements in Spain and Mexico. Its pointed reader is probably bilingual: while many pieces are presented with side-by-side Spanish and English versions, some are not, though the magazine offers English and Spanish translations of the others upon request.

Literal sets out to “provide a medium for the critique and diffusion of the Latin American literature and art,” and, at least in this issue, it is heavy on critique. Unlike the majority of literary magazines I am familiar with, most of Literal consists of short critical articles, with subjects ranging from a Picasso exhibit, to Philip Roth’s retirement, to social movements in Spain and Mexico. Its pointed reader is probably bilingual: while many pieces are presented with side-by-side Spanish and English versions, some are not, though the magazine offers English and Spanish translations of the others upon request.

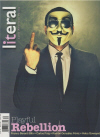

A look at the cover—a photograph of a man in a suit, wearing a mask and sticking up his middle finger at the camera and the reader—may lead one to believe that Literal takes an overtly leftist, and maybe subversive, stance in its pages. Plenty of space is in fact devoted to reportage of movements questioning the status quo. However, the writers in Literal do not hesitate to criticize the questioners themselves. For example, Carlos Puig’s commentary on the YoSoy132 (“I Am 132”) movement in Mexico takes issue with its vision. YoSoy132 began in May 2012 at the Ibero-American University in opposition to the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) presidential candidate Enrique Peña Nieto and the alleged favoritism by Mexico’s two nationwide TV networks of the candidate. Puig points to the non-partisan platform of YoSoy132 as part of the reason that the movement has lost steam: “How is it that a movement that was born vigorous, as a confrontation to one candidate, call itself non-partisan and neutral among the candidates?” (Note: The piece is written in Spanish; this quote was translated by the reviewer.)

Similarly, “15M and a (More or Less) Revolutionary Tradition” by Ramón González Férriz does not refrain from pointing out what the Spanish 15-M movement, and their predecessors, are and are not:

It mattered little whether their ideas were any good, or even possible: the protesters tended to argue from their campsite that they did not intend to create a coherent political program, but rather were expressing their unrest and conveying it to a public opinion that was enormously receptive to any expression of dissent with the status quo.

15-M refers to the protests in Spain during 2011 and 2012 that had their origins in the European debt crisis and the ensuing austerity measures taken by the Spanish government. The first of the protests occurred on May 15, 2011 (hence 15-M). González Férriz neither gives such popular movements undue credit nor dismisses them out of hand; rather, he appraises them with a dispassionate eye:

At certain moments, the selfsame act of rebelling may seem like a good idea, even though the possibilities of attaining victory are remote . . . But beyond all of that, and beyond how they see themselves, these movements act for all of society as a sample of the possibility of rebellion, of confronting power no matter what the final result may be.

John Plueker poses the question to the reader—or, rather, the viewer of the images that are the subject of his essay—“What do you really want to see of war?” The images are from an exhibition at Fotofest in Houston called Crónicas: Seven Contemporary Mexican Artists Confront the Drug War. For Plueker, the exhibition questions the ability of photographs and videos to show what is really going on. More than other media, photographs and videos promise to render reality as it is, especially on a subject like the Mexican drug war that has been reported and even sensationalized ad nauseum. However, the images reprinted in Literal challenge any assumption that the viewers may have that they “know what is happening, that they are in touch with the ‘real.’” Two boys kneel on a dirt floor, holding up packages that look like bricks or packages of marijuana in a video still from Edgardo Aragón’s Efectos de Familia: even if you have read all that has been written about the drug war, what can you know about these boys?

I love Sven Birkerts’s writing for its meditative quality, and his reflection on Philip Roth’s retirement announcement and the writing process does not disappoint. The honesty is typical: “And I do wonder: why do I care so much? What do I gaining [sic] by daily setting myself the writing task and then—I sound like Roth—so often failing to make good?” The answer that Birkerts reaches for is personal. For him, writing is a “way of inhabiting the earth,” as Natalia Ginzburg once wrote. The answer is neither grandiose nor hollow. I trust it.

Literal is a challenging but rewarding read. It also reminds the Anglophone American reader how close Latin America is: in their midst, even, as English and Spanish are spoken in the same room and side by side on the same page.

[www.literalmagazine.com]