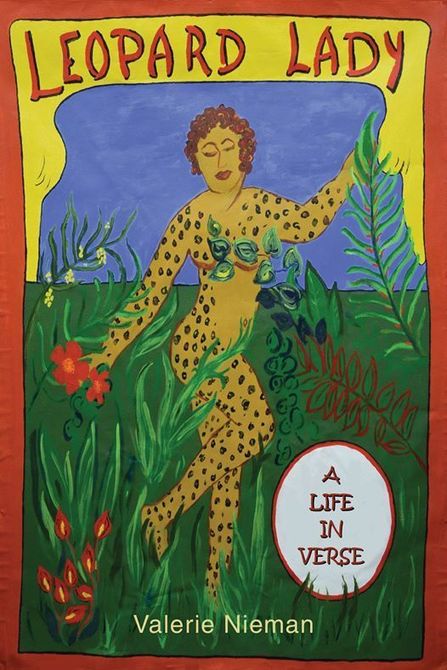

‘Leopard Lady: A Life in Verse’ by Valerie Nieman

Valerie Nieman’s Leopard Lady: A Life in Verse sweeps aside everything you might think about sideshow and carnival performers of the mid-20th century. Her poems open up the private life of a mixed-race woman, Dinah, the titular Leopard Lady.

Valerie Nieman’s Leopard Lady: A Life in Verse sweeps aside everything you might think about sideshow and carnival performers of the mid-20th century. Her poems open up the private life of a mixed-race woman, Dinah, the titular Leopard Lady.

Valerie Nieman’s Leopard Lady: A Life in Verse sweeps aside everything you might think about sideshow and carnival performers of the mid-20th century. Her poems open up the private life of a mixed-race woman, Dinah, the titular Leopard Lady.

Valerie Nieman’s Leopard Lady: A Life in Verse sweeps aside everything you might think about sideshow and carnival performers of the mid-20th century. Her poems open up the private life of a mixed-race woman, Dinah, the titular Leopard Lady.

Early on, Dinah addresses her biracial status:

I am half one thing half another

they say, but I am only one creature

in this world. My father’s skin set me

out as a Negro, so called, but only half

of me harks to my father

Her Irish mother died in childbirth, and Dad apparently hit the road. She is therefore sent to an older, childless couple, the Gastons, to be raised. It’s not an ideal situation, and as a teen, she “lit out for the woods / to be shed of old missus Gaston and her switches.”

Many of Nieman’s poems are written in Appalachian vernacular, bringing rise to the English teacher in me when I’d come across lines like, “are them spots just painted on” and “Don’t you got no people?” But I stopped wincing, got into the story, and thereafter couldn’t put it down.

Once Dinah is on her own, she encounters a fortune teller—the automated kind—in an arcade. It is the prelude to meeting a live fortune teller at a carnival where Dinah explains to her that “she can see” things. She joins the traveling show, and her life takes a turn in “How I Was a Jig” when she’s told:

We got a kootch show, and I got two

colored, plus you, as you’re willing,

to make a jig show for the crackers.

As things go, she marries a “new ride jock, / name of Shelby. [ . . . ] Now you ask how it is that I / couldn’t foretell his leaving.”

Leave, he did. And here her life takes another turn when she’s afflicted with vitiligo, which Dinah describes in “The Gypsy”:

First my hands spotted, as though someone

spattered bleach across em.

Then my elbows, knees,

like a map of some other world [ . . . ]If my mother takes me all

at last, til there’s no shade of my father,

then what will I be?

She continues in “Given Name”: “When the spots showed on me, / I changed my name like my skin, / The Leopard Lady.” She becomes a key attraction, due in no small part to the shouts of the carnival barker:

[ . . . ] touch her

spots your very self, meet this strange mortal

suspended between the human and the animal.[ . . . ] And for the menfolk, a very special offer inside,

see what that silky scarlet kimono hides!

Fortunately, Dinah’s luck with men changes when the “new inside man” arrives, a man who tenderly takes her hand, treating everyone like equals. Jonathan, aka The Professor, has his own affliction, which we learn in “The Professor: Abracadabra”:

They come visiting the ward in skewed

skirts and outdated suits. Our Pinhead sports

a slouch hat, failing to pass as rube. Fat Girl

and Alligator Man and King of the dwarves—[ . . . ] (Gawkers slow their steps and rudely stare

as my friends gather to hear my one true tale.)

Born blue, I explain, and my arteries

rerouted, but my heart will kick and dance,

the blood trying to find that old wrong road

around my heart.

Neiman brings fact into her verse with mention of the real-life conjoined Hilton twins, Daisy and Violet, creating a deeper, realer connection between her text and the reader. As Jonathan tells it:

I [ . . . ] saw

a boy leap back from where he’d tried to peek

beneath their skirts.

[ . . . ] They all do it, Daisy said, they try

to see how tis the two of us are joined together.

The twins finally settled in Charlotte, NC, working at the Park ‘n Shop. Neiman illustrates their show-biz retirement with these words:

Shoulder to shoulder, half turned away from one

another, the famous twins swung and swayed

as Daisy weighed the produce and Violet

put it deftly in the sack.

Leopard Lady is a truly amazing book that succeeds in several areas. It illuminates how carnival artists are united by the very diversity that sets them apart from commonly perceived norms. It reveals the life of one woman who, it turns out, is more like every woman than may be imagined. And for those not inclined to read poetry, Nieman’s writing is so skilled, so smooth, that her poetry unfolds like a piece of fascinating prose.

Review by Valerie Wieland