At a time when I hear people lament there are “too many books” in our culture, concerning the topic of this particular book, there are far too few.

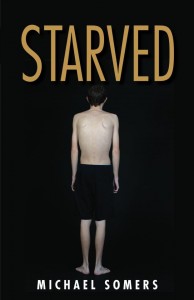

Starved (

Rundy Hill Press), written by my teaching colleague Michael Somers, is a young adult novel about male eating disorders. Often overlooked or discounted as “serious,” 10 – 15% of people with anorexia are male, and these men are less likely to seek treatment for the disorder because of the perception that anorexia is a “woman’s disease.”

This is all the more reason why books like

Starved are so critical to have in publication and in the hands of young adults. So often, books go where adults cannot to open up connections and conversations with young adults.

Starved is a way in, a bridge builder, and a wake-up call for some.

Nathan, the young male protagonist of the story, is entering his senior year of high school after a grueling junior year where he spent much of his time in school and studying. His heavy school load led to stress, which led to eating: “I could polish off a bag of Doritos in one night, which caused Mom stress of her own. ‘That’s not healthy, Nathan,’ she said, wrinkling her nose. ‘Why don’t you eat some fruit and cheese instead? You’re going to get fat.’ Thanks, Mom.” Nathan vows to improve his physique and spends the months before senior year exercising. Excessively. Not only does Nathan have his own social image and fitting in to worry about, inherent in all high school situations, but he has the pressure from his parents to do well, to achieve.

Mom and Dad, Astrid and George, belong to the social upper crust. Dad is “Mr. Super-Busy Lawyer Man” who prefers to hide behind his Wall Street Journal at the dinner table, issuing snarky remarks, and Mom is “Mr. Super-Busy Lawyer Man’s Overextended Stay-at-Home Wife” whose glass continually clinks with ice and vodka. To them, Nathan is their external showpiece, but inside the house, he is largely ignored, talked around and over, but rarely talked to except to berate with cutting remarks. “My parents brought their issues home to roost on my shoulders more and more over the summer, like a couple of screeching parrots. Something was changing. Dad stepped up criticizing Mom and me, and Mom stepped up trying to make everything, including me, a trophy.” There’s no wondering what exacerbates Nathan’s need to exert control over his world in some way, the common response factor that leads young adults into eating disorders.

Somers’s portrayal of Nathan reflects the world of the characters and their relationships to one another. Written from points of view that alternate, some chapters focus on Astrid in third person, some from the counselor’s and doctor’s notes, but most in the first person from Nathan himself. Nathan’s role of victim within his family does not discredit his validity as narrator. Somers has Nathan provide accounts of his interactions in brief detail, then spends more time inside Nathan’s head, providing the running monologue of how Nathan chooses to respond while at the same time trying to figure out who he is and where he wants to go with his life. Unfortunately for Nathan, there is not a lot he can consider other than his own body and how he can control it through eating, throwing up, and not eating. Instead of thinking about a future for himself, Nathan is continually stuck in his present, stuck in his body, and at the same time, trying desperately to get out.

It is at times a very uncomfortable read. As much as the reader wants Nathan to snap out of his behavior, out of his mindset, it is all too clear he has nothing to snap out to. There is a kind of cold chill that runs throughout the book as Nathan’s disorder progresses. It’s the same cold chill that runs through Nathan’s family life. There are no warm fuzzies in this reading, and no easy rescues. Somers will not save either the reader nor his own character and takes us on a slow, disconcerting descent into the darkness of this disorder.

Nathan sets up rules for himself. He can buy junk food, but can’t eat it, storing it in a “trophy box” under his bed. He has to do jumping jacks – hundreds of them each day. He can’t eat fats before noon. When he does eat, he makes himself purge to the point where he can vomit without sticking his finger down his throat. The times Nathan is “tempted,” Somers takes the reader through Nathan’s every torturous thought that must be suppressed and controlled. At one point, Nathan gives a friend a ride, stopping off to get some snacks. After he drops her off:

At the stop sign at the end of her subdivision, I noticed her candy bar wrapper on the floor. I leaned over, picked it up, and saw a smear of chocolate on the shiny surface. I lifted it to my nose and took a deep breath. My head popped from the smell, and I felt intoxicated. Before I knew it, my tongue licked the chocolate clean from the wrapper, but I couldn’t stop. I kept licking the way a dog licks a plate long after it’s been clean of leftovers. A horn honked behind me, and I threw the wrapper down and floored it through the intersection, not looking to see if there were any cars coming.

There are more haunting images of Nathan, like when his mother finds him passed out on the living room floor, causing her to dial 9-1-1: “She couldn’t help but see, with Nathan on the floor like a dead body, just how razor thin he had become. His fingers were nothing but bone. The visible side of his face was like a tautly covered skull. She could see his eye sockets and the hinge of his jaw right there, just under the skin.” Somers turns over several chapters to the mom, Astrid, as she struggles to deal with her son’s illness during his in-patient treatment while maintaining the family image in society. Forget the dad; George will have none of it, and so much as tells Nathan this during a family therapy session. When Nathan is well enough to leave, he will not be invited back home.

The larger portion of the book is spent with Nathan in a treatment center for young adults with eating disorders – where he is the only male patient. The story continues Nathan’s sense of confinement, as he is not allowed to leave the facility, yet for the reader, there is some relief in hoping that Nathan might now receive some help and began to heal from his disorder. Nathan is resistant at first, doing jumping jacks on the sly, taking the liquid Ensure over eating meals (which he learns is actually more loaded with calories, so he accepts the real food). It is a long, complex process for him, and Somers does well to convey this to the reader, providing the running monologue of the struggles Nathan still faces in choosing to eat or be force fed, in having to deal mentally and emotionally with each pound he gains:

My first magic number was 122 pounds. That’s when I could do yoga and Creative Movement and volleyball. My second magic number was 130 pounds. That’s when I could go off the unit but stay in the hospital. My big granddaddy get-me-discharged magic number was 145 pounds. When I first got here, I weighed 112 pounds, so those numbers seemed pretty big to me at first. It may as well have been 200 pounds to gain. From where I sat, there wasn’t much difference. But as I got to 120 and 121 pounds, believe me, I noticed the difference. Freedom, or something sort of like it, was within reach now.

Nathan’s ongoing work with his counselors also helps him to confront his parents during family therapy for their part in his life choices, and eventually, understand his father is at the root of his greatest fear:

“I was afraid of being like him, God. I was afraid too much had been leveled by the cyclone that passed from George to me. I was afraid if I ever got married and had kids, I’d do to my family what George did to Astrid and me. I was afraid that I was no good and couldn’t be fixed.”

Nathan has many small moments of struggle, with the counselors, doctors, and other inpatients, that he continues to work through. The therapy moments are much what you would expect from teens – non-compliance, non-participation and sarcasm. But one session in particular provides a turning point for Nathan: when the residents are asked to lie down on long pieces of paper and have their body outlines drawn for them to see:

What I saw made me think of the cop shows and the chalk outlines of dead bodies. There I was, down on that paper, drawn out in black marker, like a dead person. I didn’t take up much space at all. The outline looked so thin. I felt huge though! There I was, on the floor, not huge at all. It was like Steve had taken someone from a concentration camp and drawn his body. That couldn’t be me; it couldn’t I couldn’t figure out what I was seeing . . . Who was this skinny boy on the paper? And what happened to him? Where were his parents? Why did they let this happen to him?

The best way for eating disorders to succeed is to not talk about them, to not even acknowledge their existence. Somers’s treatment of this malady in our society is one that confronts but does not dramatize, which would be easy to do and turn the subject matter into a kind of bad, after-school special. The way Somers presents the story, through Nathan’s logic, makes it so the reader, while not agreeing with what Nathan is doing, can completely understand why he is doing it. Somers creates a character through which a mental health disorder can be understood, which is what lifts this book above teen angst narrative. Through Nathan’s thoughts, we can clearly see his triggers, his reactions, and his resistances, his cries for help, and manipulation to avoid help. Whereas some people read stories set in foreign countries to learn about those places, this book can be read to better understand the mindset of the individual with an eating disorder.

Does Starved have a happy ending? It’s hard to say. Nathan lives, that much I think I can safely give away. But, as is the course with such mental and emotional disorders in our society, eating disorders are for life. Nathan’s gaining enough weight to earn a day pass is only the beginning of what he will need to continue achieving on his road to recovery if he hopes to truly live again. I think Somers would like to have us believe that Nathan has been helped and that there is hope, but the reality this young adult novel delivers is that happily ever afters are for fairy tales. Nathan, just like the rest of us, has a long road ahead of him, but at least he has a road, and that’s way better than not having one at all.