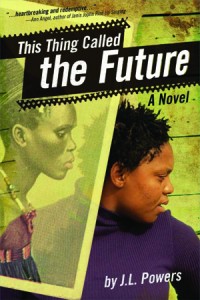

What I’m Reading: This Thing Called the Future

This Thing Called the Future (Cinco Puntos Press, May 2011) is the second young adult novel by J.L. Powers, better known around NewPages as Jessica. Jessica has been connected with NewPages for nearly a decade, writing reviews, feature columns and interviews. She is also editor of The Fertile Source, a literary ezine devoted to fertility-related topics, and publisher of a number of collections with her press, Catalyst Book Press.

This Thing Called the Future (Cinco Puntos Press, May 2011) is the second young adult novel by J.L. Powers, better known around NewPages as Jessica. Jessica has been connected with NewPages for nearly a decade, writing reviews, feature columns and interviews. She is also editor of The Fertile Source, a literary ezine devoted to fertility-related topics, and publisher of a number of collections with her press, Catalyst Book Press.

Her first young adult novel, The Confessional (Random House/Laurel-Leaf, 2009), endeared her fiction writing to me, especially after it was banned from (and her speaking engagement cancelled with) the Jesuit high school that influenced the setting for the story. I taught the book in my college developmental writing class, and while it was challenging – dealing with issues of drugs, alcohol, homosexuality, immigration, racism, and all starting off with a murder – it was very well received by the students because of its honesty in discussing real-life issues. This Thing Called the Future might be the book to take its place. No less controversial, and no less honest in dealing with difficult subject matter, This Thing Called the Future is the story of 14-year-old Khosi set in HIV-ravaged South Africa.

The story begins –

A drumbeat wakes me. Ba-Boom. Ba Boom. It is beating a funeral dirge.

When I was my little sister Zi’s age, we rarely heard those drums. Now they wake me so many Saturdays. It seems somebody is dying all the time. These drums are calling our next-door neighbor, Umnumzana Dudu, to leave this place and join the ancestors where they live, in the earth, the land of the shadows.

– and follows Khosi through several weeks of her life, living with and caring for her aging grandmother and little sister while their mother works away in the city to help (just barely) support them. The story deals very openly and matter-of-factly about the threat of HIV for young girls in Africa, but does so through the strength of Khosi’s character – providing a clear and level-headed role model for any young adult responding to such challenging life issues. Khosi watches her careless friend Thandi involve herself with older men (who prefer younger girls less likely to have been exposed, and virgins most especially). Khosi cautions Thandi against her reckless behavior, warning her time and again of the dangers of HIV. Thandi’s response is unfortunately typical of so many young people who believe they are infallible. Any young reader will have no trouble identifying with Khosi’s rational and sexually conservative stance of self-preservation.

In addition to this clear front message of the book, Powers includes a great deal of South African Zulu culture as it straddles the generations and struggles to survive. Powers’s own background includes a master’s degree in African History from State University of New York-Albany and Stanford University, a Fulbright-Hayes to study Zulu in South Africa, and serving as a visiting scholar in Stanford’s African Studies Department in 2008 and 2009. Her acknowledgements for the book give credit to a number of people with whom she worked in Africa to gain education and insight into the culture, as well as to live it day in, day out. This becomes fully integrated into the writing with the use of Zulu language throughout the text, and a full glossary of the terminology in the back of the book. This is the best kind of cultural exposure and immersion for young (and old) adults. Because there is repetition of key terms and concepts early on in the writing, readers come to learn this language by the end of the book.

Khosi’s character and her relationship with the women in her family and the women in her community provide the symbol of the struggle for Zulu cultural survival. Khosi’s grandmother believes in the traditional medicine and healing rituals of the Sangoma (female healer) and engages Khosi in a ritual cleansing with her. Khosi’s mother has abandoned these ‘ancient ways,’ but also is either not accepting of contemporary, Western medicine, or is in denial of needing it. Khosi often finds herself conflicted, growing up in this divide of adults and their beliefs. Through the scope of the novel, she comes to make her own decision about what she will choose to follow – traditional medicine to help heal her AIDS-ravaged community, or the way of the sangoma to maintain the strong connection with her ancestral roots.

While Khosi’s character provides a strong model of coming to “right behavior” in a variety of situations, understanding how scary and difficult it can be to make the right choices is only evident because Powers writes this fearlessly into the novel. Without knowing the truth of what exists and what young people face – in South Africa, in the United States, in ANY country – we cannot have the real and truthful conversations about what is right behavior, what it means to self-preserve, and what it means to honor both the past and the future. This Thing Called the Future does it all through the voice of a South African teen, tiny in stature, but large enough to shadow all we see looming.

Many YA titles deal with controversial subject matter, and I can only imagine many of them do not make it onto school reading lists. I am hopeful, though, that the young adults themselves are still finding access to these books – in libraries, bookstores, or on their personal e-readers. Controversial subject matter is the most difficult to discuss with young people, and all the more why it needs venues – such as books of fiction – that make it accessible for them to find.

The first five chapters of This Thing Called the Future are available on Powers’s website, as well as AIDS & South Africa: A Teacher’s Guide to This Thing Called the Future.