A Moveable Famine

John Skoyles, poetry editor of Ploughshares and professor at Emerson College, unveils in this memoir his journey as the son of a working class family in Queens whose mother introduces him to poetry, to student at a Jesuit all-male college, to the Iowa Writers Workshop, Provincetown, Yaddo, and a long, successful career as professor and published writer. He takes the reader along through his interactions with intimidating professors, competitive classmates, indifferent women, and flawed mentors. He skillfully weaves the diverse elements John Skoyles, poetry editor of Ploughshares and professor at Emerson College, unveils in this memoir his journey as the son of a working class family in Queens whose mother introduces him to poetry, to student at a Jesuit all-male college, to the Iowa Writers Workshop, Provincetown, Yaddo, and a long, successful career as professor and published writer. He takes the reader along through his interactions with intimidating professors, competitive classmates, indifferent women, and flawed mentors. He skillfully weaves the diverse elements of his story in a way that reveals how nothing was wasted, how every pleasant or painful encounter contributed toward creating his life as a poet.

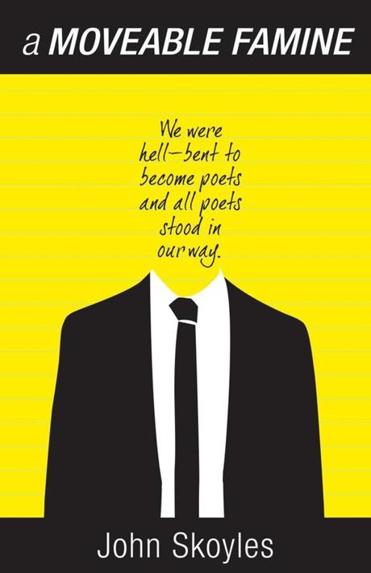

Printed on the cover, almost like a subtitle, is the book’s recurring theme, “We were hell-bent to become poets and all poets stood in our way.” This sentence begins the “Preface,” after which Skoyles explains, “We had been outcasts in high school, stars in college and had graduated from finishing school in the art of verse.” Skoyles describes how he and his peers learned to see the world through the lens of poetry and how they explored depths of emotion inaccessible to others, which explains his conclusion, “We forged friendships with poets who loved our poetry. Poets with whom we would tap, knock, bang, and finally demolish the doors of poetry’s academies, societies and foundations.”

The phrase appears again in the third chapter, which begins, “We were hell-bent to become poets, but we were students. Those who taught us were hell-bent to become poets, but they were teachers.” In this chapter, Skoyles uses visual details to introduce the reader to the faculty at the Iowa Writers Workshop, including the director, a former navy lieutenant, whose “sharp gray suit matched his silver hair and silver tie tack in the shape of a martini glass”; Mitchell Lawson, “the elder statesman of the poetry faculty” whose “bowl-shaped haircut and the bangs across his forehead made him look like an actor in a movie about the Holy Roman Empire”; and Harvey Clay, the other permanent member of the poetry faculty, a stocky man who wore turtlenecks and a goatee; heavy-drinking and cigarette-smoking John Cheever, who traveled exclusively by taxi; and Raymond Carver, whose car windshield was scarred with a bullet hole. Skoyles also describes some of his classmates, including Denis Johnson, roaming the halls barefoot, and friends McPeak, Ridge, and Pryor, and the bar called The Deadwood, where they gathered to talk poetry and drink beer and whiskey.

Although Skoyles intersperses passages of poetry throughout the book, the prose describing mundane situations often contains the elements of poetry. He portrays a girl at The Deadwood as, “the girl whose eyes seemed to melt like snowflakes.” When Professor Lawson reluctantly takes the stage to read to a crowd, Skoyles writes, “Lawson moved like a scarecrow dragged by a farmer to its post in the field.” And, “If before he seemed a man awaiting the firing squad, now he looked as if a few bullets had grazed him at the knees.” Referring to a classmate about whom he fantasizes romantically, “Glimpsing her was like writing a few decent lines that trail away as the muse deserts the page.”

Skoyles repeatedly portrays poetry, more than art or craft, as a lifestyle for him, his peers, and teachers. Two of his professors, Lawson and Neil Clarke, play a game they call Stevens, the rule of which is that upon meeting, their first words to each other must be a situationally appropriate quote from Wallace Stevens, emphasizing their vast knowledge of poetry and the ubiquitous competition of the Iowa Writers Workshop. For example, Clarke approaches Lawson, who is walking Uncle, his neighbors’ homely dog with bloodshot eyes and protruding teeth, which Lawson adores and sometimes borrows, and says, “There are not enough leaves to cover the face it wears. . .” to which Lawson replies, “The creator is too blind.”

Among the most tender passages of the book are those that portray Lawson’s affection for Uncle. Skoyles, Lawson’s recently appointed research assistant, helps trim Uncle’s claws, watches Lawson treat the dog’s infected eye with ointment, hears him lament the dog’s suffering under the neighbors’ neglect. Skoyles describes the scent Uncle leaves behind, “like a rainy day in autumn—decay, wet leaves and mud.” Skoyles recounts finding the stoic Lawson sitting alone in the dark in his office late one night, “It looked like he’d been crying. Cabaret music played from the small cassette recorder.” The neighbors having told Lawson they’d sent the dog to live on a cousin’s farm, Lawson grieves, convinced they’d euthanized him, “This voice. . . It’s like him talking from beyond the grave.”

Less competitive and more laid back than Iowa, Provincetown provides the backdrop for more social and romantic forays, where drinking becomes more endurance sport than sociable activity and actions have enduring consequences. A Moveable Famine reveals the joys and sorrows that help a young student mature into a poet and teacher. Hell-bent on becoming poets, Skoyles and his peers seem to exemplify the words of their Provincetown mentor, Stanely Kunitz, “The heart breaks and breaks and lives by breaking.”