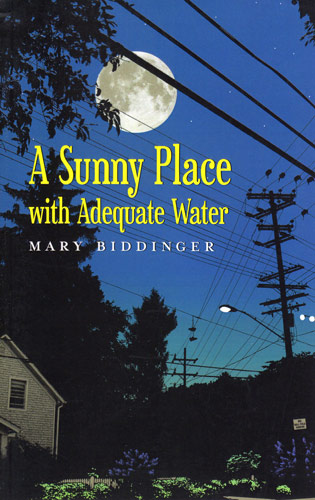

A Sunny Place with Adequate Water

Mary Biddinger’s fourth poetry collection, A Sunny Place with Adequate Water, grapples with social mores, loneliness, and isolation through serial non-sequitors and questions that seem sincerely non-rhetorical, yet go unanswered. Tonally, A Sunny Place with Adequate Water is reminiscent of the poetry of Mary Ruefle, or of Steven Millhauser’s prose poem novella, Enchanted Night. Mary Biddinger’s fourth poetry collection, A Sunny Place with Adequate Water, grapples with social mores, loneliness, and isolation through serial non-sequitors and questions that seem sincerely non-rhetorical, yet go unanswered.

Tonally, A Sunny Place with Adequate Water is reminiscent of the poetry of Mary Ruefle, or of Steven Millhauser’s prose poem novella, Enchanted Night. The book is very much grounded in the real—there is no explicit magic or supernatural activity taking place here—but the personification and if/then constructions Biddinger uses tend to make emotional, rather than logical sense, giving the poems an ethereal quality nonetheless. “It was the year the trees decided / to kill each other, and then us / and then each other again,” opens “A Coin-Operated Arboretum,” before ending ultimately with the speaker defying her mother.

Preoccupied with an unrequited longing to have one’s humble needs met and to achieve a baseline “okayness,” many of the poems undercut their innocent beginnings with moments of petty violence, or with images that otherwise create sinister undertones. Biddinger’s images are often innocuous at first, but as they accumulate in a poem, they begin to take darker turns. In “A Tiny Poison Eye,” for example, images of childhood play—hoops, rocks, trophies—shift midway through the poem. “I was among an inhospitable element. Like anyone would fall for the trick of what’s in my pocket,” the speaker says, and then admits, “we were both altar boys, until we cut hands / on the same pricker bushes,” and finally focuses on the speaker’s grandfather taking his eye out, mingling the innocent with the grotesque and implicating the reader for daring to read into what has been offered.

As the book jumps from one idea to the next, it’s held together by the repeating “coin-operated” conceit, as well as by consistencies of form. The poems are structured as one-line stanzas, couplets, tercets, and prose poem blocks, giving the progression a balanced orderliness on the page; formal tension created by the tidy couplets and tercets is periodically released through the freeing prose block form.

“There was nothing I wouldn’t do to restore order,” the speaker states in “Occupation: Hazard,” and as a whole, the book is preoccupied with order and fitting in—with how individuals become part of a neighborhood, with social pressure, and, in “A Coin-Operated Apple Pie,” with American pride and the met and unmet expectations that pride imposes. How do we cope with social pressure, and what do we compromise by settling into the sunny place of our own neighborhood? Biddinger allows readers to arrive at their own answers to these questions.

The perspective is often given from the first person “I,” and that speaker often addresses a “they” or an “it” rather than a “you.” This is a book engaged with ideas about the individual and society instead of intrapersonal relationships. The speaker’s relationship with community—most commonly expressed here as the neighborhood in which the speaker lives—is a fraught one, one that places undue expectations and tends to stifle. This is reinforced by the nostalgia inherent in the “coin-operated” conceit of many of the poems, which evokes automats, tin toys, and video arcades.

Poems like “A Coin Operated Arboretum” or “A Coin-Operated Apple Pie” may be dark, but the collection maintains a sense of hopefulness and levity nonetheless, seeming to posit that not-belonging can itself be a way of belonging, and feeling at odds is just another way of homemaking. After all, as “Inside Every Vending Machine It’s 1979” concludes, “Everything / is looking for a way out, or a way back in.”