A Turn Around the Mansion Grounds

A Turn Around the Mansion Grounds: Poems in Conversation & a Conversation is the third chapbook in a series that pairs two female poets, one well-known and the other a rising talent. Molly Peacock is widely anthologized and published in leading literary magazines in addition to her six volumes of poetry. She also helped create New York’s Poetry in Motion program. A decade ago, Peacock mentored Amy M. Clark. Meanwhile Clark’s poetry book won the 2009 Vassar Miller Prize in Poetry.

A Turn Around the Mansion Grounds: Poems in Conversation & a Conversation is the third chapbook in a series that pairs two female poets, one well-known and the other a rising talent. Molly Peacock is widely anthologized and published in leading literary magazines in addition to her six volumes of poetry. She also helped create New York’s Poetry in Motion program. A decade ago, Peacock mentored Amy M. Clark. Meanwhile Clark’s poetry book won the 2009 Vassar Miller Prize in Poetry.

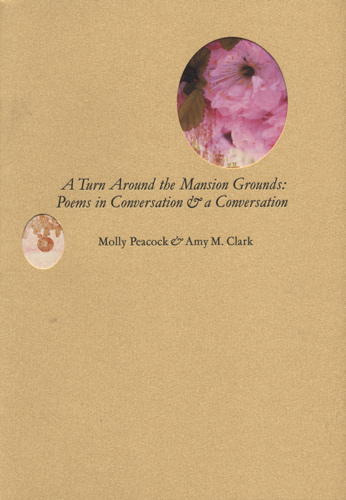

The limited edition chapbook is an entirely beautiful work, beginning with the glimmering gold cardstock cover designed by Kara Kosaka, who chose to feature pink blooms and a chandelier peeping through oval cutouts.

Once inside this fresh presentation, you’ll find a juxtaposition of eight poems by each poet. Peacock was initially invited to select a partner for this “call-and-response” collaborative. She chose Clark, who laid out the sequence of poems.

I wonder why Clark opened with her poem called “Arc.” I felt that poem to be less impressive than others. Her three sonnets, “My Bluest Lake,” and two from her book Stray Home, “vii” and “viii,” stand out. “My Bluest Lake” begins:

They said envision what you love. Cold lake,

blue room. It would be over soon. Undressed,

I swam although my chest began to ache,

then climbed a mica-glinting rock to rest

At first glance I thought I’d write a comparison of the women’s works, since each neighboring pair addresses a specific theme, but I discovered their contrasts to be more interesting.

Clark’s works unfold gently. In “Dumb” she writes:

But the babysitter said, “Lick

the porch railing.” We watched her flick

an ash onto the snow, air thick

with her mouth’s steam.

Peacock’s response to “Dumb” is “Good Girl,” in which, like most of Peacock’s poetry, everyday words undergo a transformation.

Hold up the universe, good girl. Hold up

the tent that is the sky of your world at which

you are the narrow center pole, good girl. Rup-

ture is the enemy. Keep all whole.

Clark’s “Do You Want to Hold the Baby?” answers the title question:

All of me wants to fall upon the brittle

invoked by childless women of a certain age:

“Oh, no, babies don’t like me. Usually,

I make them cry.”

Peacock teams this with “And You Were a Baby Girl”:

[ . . . ] I catch the tender

spark of the faint comet of your infant

smell, still, and am shocked and won’t surrender

and then do—

The conversation portion of the book is exactly that: two poets discussing how they work together and analyzing some of their poems. “Working together so intuitively makes me wonder how collaborations incubate,” writes Peacock. “A decade is a big leap in a literary partnership; here our leap is from student and mentor to two poets in a think-y gabfest [ . . . ]. And, “The term ‘verse’ (inside ‘conversation’) derives from ancient agriculture, the line of the plough that tills the ground; the turnabout with the plough makes the next line. [ . . . ] The sense of lines walking and turning in a poem echoes the idea of walking and talking together.”

I especially like Clark’s “Belongs To”:

She bequeaths to me a lidded white and black bowl.

Gustavsberg, she says. It’s worth something.Riding in the front seat, the dish is a small child

without a booster. My arm shoots out when I brake.

Peacock’s response: […] “I needed something of mine that would correspond, follow, and close the chapbook. That was a tall order.” She meets that tall order with “George Herbert’s Glasse of Blessings.” Her point of departure is “The Pulley,” by the 17th century devotional poet Herbert. His poem begins, “When God at first made man, / Having a glasse of blessings standing by;”. He repeats the word “rest” several times, as in “Perceiving that, alone of all His treasure, / Rest in the bottom lay.”

Peacock takes a decidedly more secular tone:

REST. George Herbert poured it last from the glasse.

People find it only at the bottom.

When I rolled down to the bottom

of the hotel bed, and the cell phone lit

with your number, I thought my torso has pressed it

I was curious about the title of the chapbook. Peacock offers an explanation: “The Mansion of our title resides in our imaginations, but its prototype is a nineteenth-century grand manor in Louisville, Kentucky.” That manor was later encased entirely inside a classroom building. And that was where that Peacock first met Clark.

A Turn Around the Mansion Grounds: Poems in Conversation & a Conversation is an uncommon and entertaining addition to any poetry lover’s collection.