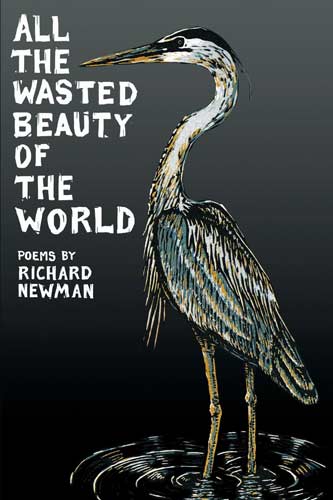

All the Wasted Beauty of the World

The cover image of Richard Newman’s All the Wasted Beauty of the World is “Great Blue Heron of Southern Indiana” by Nick Nihira and the thirty-nine poems are divided into four sections: 1. Summer Spells; 2. Autumn Contrails; 3. Winter’s Bloom; 4. Spring Necromancies. I assumed the poems would be about nature by the cover and title, and the poems would be in a metrical style since the publisher is Able Muse. That is the delightful surprise about poetry and reviewing—as neither was entirely the case. The cover image of Richard Newman’s All the Wasted Beauty of the World is “Great Blue Heron of Southern Indiana” by Nick Nihira and the thirty-nine poems are divided into four sections: 1. Summer Spells; 2. Autumn Contrails; 3. Winter’s Bloom; 4. Spring Necromancies. I assumed the poems would be about nature by the cover and title, and the poems would be in a metrical style since the publisher is Able Muse. That is the delightful surprise about poetry and reviewing—as neither was entirely the case.

The images are strong, such as in the first poem, an ode, one of four in the collection. “Ode to the Urban Mulberry” is described as a “Junk tree. Weed grown thick as an old man’s wrist.” Again, a poem called a lullaby about the plight of homeless people, ends with: “and though your day’s too wide to cross / night always takes you back.”

As a writer of triolets, I was thrilled to see “Three Triolets on Lines from Public Places” unexpectedly incorporating an airport, Busch Stadium and Craigslist as topics. They brought a wide smile because this type of poetry of eight lines requires a tight rhyme pattern with careful word choice. It was followed by a sonnet of fourteen lines, another form that calls for close attention.

The second group of poems, “Autumn Contrails,” begins with a piece about the heron on the cover: “This gangly king, somber comedian / stretches his S-trap neck and Tinkertoy legs” as it looks for food. Readers who have trouble sleeping will especially appreciate the poem “4a.m.”—the sounds and activities that abound in the early hours when one cannot sleep. In fact it is the time I began this review and certainly agree with his line: “Would James Bond lie awake like this?” And relate to the “. . . blue beginning at last to creep through curtains . . . .”

The villanelle form is used in such poems as “The Ugliest Woman Sitting at the Bar”; the 19-line format is a delight to write but difficult not to make “sing-song” because of the required rhyme scheme. Newman selects the words with an enviable ability to fit what he has to say and satisfy the form. The reader gets a clear picture of the woman at the bar. The form is used again in “Please Be Advised,” the repetition of the villanelle reinforcing the topic of the poem. In “Advice to the Youth of America” the form flows so well with the narrative that the reader forgets it is a villanelle.

It is in common places that Newman gives the reader some of the most pleasing pauses: “Technology enables our worst instincts / religion sanctions them.” Newman also likes to list things as in a recipe in poems: cloth, oil, candles, feathers, shells, and directions on how to use them to achieve a desired effect such as getting rid of a winter gloom.

One of the themes in All the Wasted Beauty of the World is loss, the universal need of looking back into the past; another is the existence of the mixture of good and bad, such as “There poison in the peace lily” reads Newman’s longest poem, “Bellefontaine Cemetery.”

Richard Newman’s range is wide: pictures from space of The Pillars of Creation to the seeds of cottonwood trees. Newman includes a form beginning in medieval France, the aubade, associated with the arrival of early morning. Due respect is given to cockroaches in “Ode to the Brown-Banded Cockroach”: “You know the art of waiting since you evolved / 300 million years before we did.” The passage of time and looming death (echoed in the use of black in the cover and selected inside pages) is prevalent, time that renders “tombstones weathered wafer thin” in his last poem “Bones.”

The use of sly humor, formal poetry, and close observation of people and nature makes this an enjoyable collection inviting close reading and rereading, the four parts dividing the poems with consistency. The craftsmanship of these smoothly flowing poems is to be admired. It was a pleasure to witness Newman writing with such familiarity about places across America and expertly using formal styles including ballads often frowned upon in editorial guidelines.