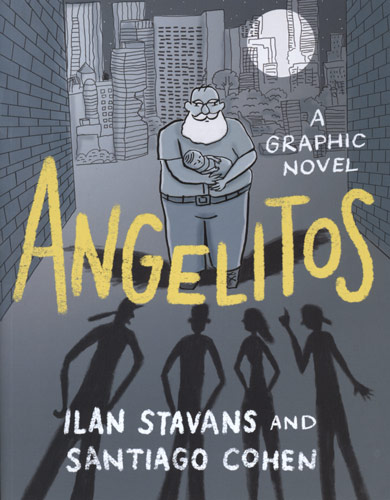

Angelitos

Reading graphic novels sort of makes me feel like I’m ten years old, but when they include issues like poverty, molestation, and the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, I realize that a ten-year-old me wouldn’t know what to think. I still don’t, for that matter. Angelitos by Ilan Stavans and Santiago Cohen throws you straight into the lion’s den of Mexico, where homeless children run amok, and the only one that seems to care is a Catholic priest by the name of Father Chinchachoma.

Reading graphic novels sort of makes me feel like I’m ten years old, but when they include issues like poverty, molestation, and the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, I realize that a ten-year-old me wouldn’t know what to think. I still don’t, for that matter. Angelitos by Ilan Stavans and Santiago Cohen throws you straight into the lion’s den of Mexico, where homeless children run amok, and the only one that seems to care is a Catholic priest by the name of Father Chinchachoma.

The story follows an aspiring writer who’s looking for a story, but stumbles into chaos instead. He forms a friendship with Father Chinchachoma and some of the children, and before long, his middleclass, rose-colored glasses shatter. At least a good story comes from it, though. That’s the main lesson of this book, actually: no matter how much madness one comes across, it all serves a purpose.

Regarding aphorisms, Father Chinchachoma, or “Padre Chincha,” is full of them. Throughout the book, his wisdom shines in sentences like, “Death is unimportant. Life is what matters.” Or, “It is imperative to be an optimist. There is no other option.” He is portrayed as a stout man with a long, white beard, almost Godlike. But in reality, Padre Chincha is no more divine than the common soul, just a person that’s willing to dedicate his life to the betterment of the community. This thought puts a smile on my face, knowing there’s no need to beg the skies for help—unless you want to, no harm in that—because a brighter world can come from us.

It’s impossible to discuss a graphic novel without mentioning the illustrations. Santiago Cohen does an excellent job maintaining a sense of dread with his black and white, somewhat scratchy drawings. Distant buildings look like cages, trapping the poor inside, or keeping them out. During the 1985 Mexico City earthquake scene, Cohen’s images become scribbles, lining up faultlessly with the pandemonium, of which I cannot even attempt to describe. Real people experienced this and dealt with the paralyzing effects of what Mother Earth can do. I, on the other hand, can only watch clips and read books, but the depiction that Cohen and Stavans have created is so palpable that I, too, can feel the pain of Mexico circa 1985, if only an infinitesimal sliver of it.

One of the most disturbing things about the book is that these children are mere products of their environment. They rob and kill because this has been done unto them. How can someone, especially a kid, be blamed for mirroring their surroundings? This is a survival tactic, one of self-sufficiency, which, in a world where the police, hospitals, and pedestrians could care less whether you’re dead or alive, is paramount.

There is a scene where one of the children, Jaimito, has been assaulted by the police, and Padre Chincha takes him to the hospital. They wait two hours for a doctor, and it probably would have taken longer if Padre Chincha hadn’t went into a tirade about the mistreatment of those without money, and how “Everyone thinks street kids are not worth one peso.”

If those that are supposed to protect and heal decide that you’re useless, what other options are there than to protect yourself, and find cures to the pain in a bag of glue? The worst part about it is that this seems to be an everlasting cycle, because the children that see eventually grow into the adults that do, unless, of course, they die young.

Forgive me, there is another alternative: jail. In Angelitos, an eight-year-old boy named Lengüita is sent to the penitentiary for begging near a metro station. According to the Human Rights Watch, more than one million children are behind bars around the world. It’s universally known that kids are, generally, quite ignorant, so where are the programs that teach them and lead them down the correct path rather than corrupt them even further?

Padre Chincha says, “If Jesus were among us, he would spend his time with the downtrodden, not with the rich.” It’s hard to imagine the beggar on the street or the woman talking to herself on the train as a savior, but what if they were? We would probably blow right past them, absorbed in our own menial problems, just as the upper and middle classes in Mexico (and all over the planet) blow past the children in need. What could we do, though? Hand money to each of them? No, but I believe that Padre Chincha should serve as an example that a little bit of effort, one day, one life at a time, can make a difference. One just needs to care, even if no else does.