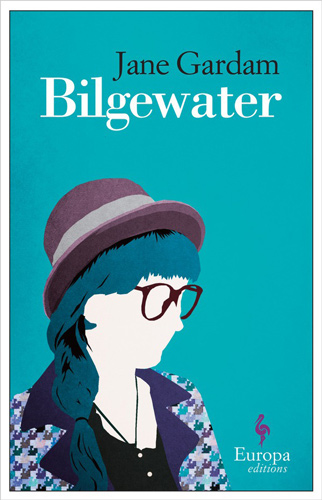

Bilgewater

For Jane Gardam fans, this new reprint of her novel Bilgewater will be a delight, almost as good as Old Filth. For those who don’t know Gardam, you’ll have a wonderful treat. There are some Gardam features which you need to be aware of: sometimes a lot of important information is given in one sentence so you need to be alert; Gardam is British, so sometimes you come across an unfamiliar expression; and this novel has a typical Gardam ending, which took this reviewer three rereads to figure out. But the discovery was fun.

For Jane Gardam fans, this new reprint of her novel Bilgewater will be a delight, almost as good as Old Filth. For those who don’t know Gardam, you’ll have a wonderful treat. There are some Gardam features which you need to be aware of: sometimes a lot of important information is given in one sentence so you need to be alert; Gardam is British, so sometimes you come across an unfamiliar expression; and this novel has a typical Gardam ending, which took this reviewer three rereads to figure out. But the discovery was fun.

Bilgewater is reminiscent of Old Filth in having an unforgettable title. Bilgewater is actually the nickname the narrator Marigold Green is given because of her appearance, which she imagines is unattractive from her lack of good conventional clothes and any care to her hair. Since most of this novel takes place while Marigold is sixteen, it is a coming-of-age story of finding a boyfriend unexpectedly and unsentimentally, in typical Gardam fashion. The novel’s epigram fits, a quote from Disraeli: “Youth is a blunder,” full of false prospects for “Filthy Bilgewater,” her nickname given by the boys.

Typically, in Gardam’s comic novels, the characters are eccentric. Marigold calls her father “vaguish.” She might as well be an orphan though her father is alive and she lives with him (her mother died in childbirth). Preoccupied by his job as housemaster and classics teacher in a boys’ school, he reacts to his daughter’s return from school by “Ah” and then goes back to his Aeschylus. The only female to attend to Bilgewater/Marigold is a young woman called Paula whose primary responsibility is to care for Marigold’s father. Paula is asked repeatedly, “Why do you stay here?” to which she answers in her peculiar way, “The dear only knows, my lover.” Despite some differences, Paula and Marigold are close with Paula giving Marigold practical and unsentimental advice like, “Beware of Self Pity.”

Marigold calls her father’s friends “quaint, barmy, odd . . . the old masters.” HB, “a Captain in some war” gassed and now 80 years old, “Puffy” Coleman, History teacher, “who always stands sideways in the School Photograph because his teeth drop out.”

And Old Price – “if he drank more than two sips he’d go up in a little wisp of smoke.”

While Paula and Marigold talk of “sin, death, love, harmony and particularly ethics,” on Learned Thursdays when the Old Masters meet, this is their chat:

‘I once saw the zeppelins,’ says Puffy Coleman.

‘I can remember the zeps. All the boys ran out along the cliff tops cheering. In their pajamas.’

‘Ah,’ says Puffy Coleman, lowering his teeth.

‘Ah,” says Uncle Pen HB. Then, ‘It wasn’t that war.’

‘Yes it was. What d’you think it was? The Napolenoic War?’

‘Scarborough was bombarded in the Napoleonic War,’ whispers Old Price.

‘Now then Price, you weren’t in the Napoleonic War,’ says Pen.

Father gazes at the uplifted wine.

‘D’you think Price was in the Napoleonic War, William?’

‘Ha, ha, ha, ha,’ says father, bewildered looking round sweetly, kindly, at one and all, not at all sure, for he is a good bit younger than the others, what might or might not be so.

They reflect.

Oh, it’s wild stuff.

Surprises abound like that Bilgewater is brilliant, eligible for Cambridge and also attractive as some boys admit. Even the ugly Terrapin boy, who called her “Filthy Bilgewater,” changes for the better. Still, there is a degree of cruelty and inconstancy associated with their age, and surprises in whom the main characters each settle down with.

Another treat Gardam offers is her British insights into experiences:

A saucer story is descended from something years ago when we were very happy—the reason has gone, and that is interesting, too. [ . . . ] These events were all usual. Other people all around us were doing the same things. Yet the memory of them doesn’t come up with a name for what went on. It was just a series of things that were important and beautiful and namelessly good, an experience proof against nostalgia, proof against the distortions of time. An experience one is the better for having had even when the brain grows soft and slow and can’t remember whether it has just locked the door or was just about to do so. Or if not why not, or if so why. Like Old Price and the zeppelins.

This is no ordinary bildungsroman. It is charming, funny and well worth the wait for it to be reissued.