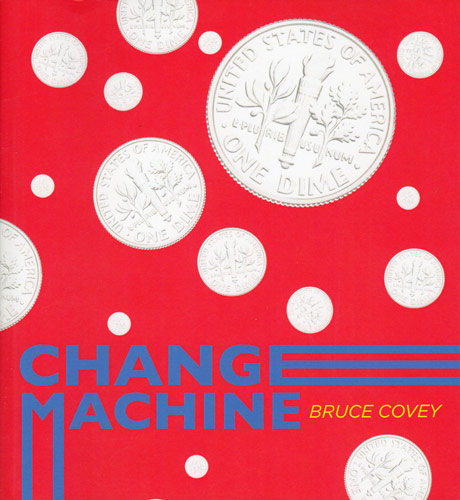

Change Machine

Bruce Covey’s Change Machine is a lively book that takes a humorous approach to formal experimentation. Among other ideas, Covey examines how the man-made world intersects with the natural one. Here, “man-made” includes human inventions both critical—mathematics, industry, philosophy—as well as trivial—puns, pop singers, imitations. The speaker’s voice is conversational but emotionally cool, and its consistency holds together a varied array of poetic forms including sonnets, near-sonnets, and imitations of iconic poems by Frank O’Hara, Alice Notley, and Ted Berrigan. Bruce Covey’s Change Machine is a lively book that takes a humorous approach to formal experimentation. Among other ideas, Covey examines how the man-made world intersects with the natural one. Here, “man-made” includes human inventions both critical—mathematics, industry, philosophy—as well as trivial—puns, pop singers, imitations. The speaker’s voice is conversational but emotionally cool, and its consistency holds together a varied array of poetic forms including sonnets, near-sonnets, and imitations of iconic poems by Frank O’Hara, Alice Notley, and Ted Berrigan.

Change Machine opens with fact—the book’s first line is “Currency is nickels & dimes & quarters / Each of which conduct electricity.” Often, they mimic the setup-punch line format of joke structure—setting an expectation that is then met in an unexpected way. The titles of Covey’s list poems operate as setups and the poems themselves become lists of possible punch lines. Covey’s puns are sometimes brilliant (Putting in “Xerox” for “Zero” in “From Xerox to Infinity,” for example), while others are quite cheap. (“Mensa: Thinks it’s smarter than it really is.”) But the poems aren’t always so certain. Taken as a whole, the multitude of puns suggest a speaker who mishears, but takes mishearing as an opportunity for double and multiple meanings, rather than inaccuracy.

One of the Change Machine’s most interesting features is the way in which it places repeating ideas in shifting contexts. For example, the line “Half of two is four, of which half is eight” suggests mechanical reproduction in “From Xerox to Infinity.” Halving returns at the end of “From Red to Ruler” as “How much it means to me to split in half, and halves again,” only here it takes on connotations of a split self, of cells dividing, and evolution of the self.

The world’s vastness is represented by the variety of things pulled in from different frames of reference and diction sets: the poems include gold and silver and salt and air, robots, Ke$ha, New York School poets, Delta airlines, Jerry Springer, John Cage, Barthes, mathematics and fruit and catapults and tulips, all of it jumbled together and spit back out again in poems that almost impose order—almost, but not quite—through couplets, through sonnet and pantoum forms. But sincere questions generally receive indirect answers, and while the list form is a consistent feature of the book, the logic governing the lists is itself variable.

It’s no mistake that the poems frequently refer to codes and symbols, without ever fully cracking any of them. As the book’s final poem “Arctangent” posits:

Sometimes repetition works and sometimes form, but sometimes too it seems that the

sounds are infinite and can travel uninterrupted, without entropy. During those moments I

feel like I need to put myself through a shredder. The world is full of many sentences.

Change Machine is structured as a dichotomy, its two sections titled “Tails” and “Heads,” but here, too, the book resists conclusion. “Tails,” the book’s first section, finishes with a satisfying ending gesture, concluding with the aptly titled “Whole.” But the book continues, and ends less certainly than it began. “Arctangent,” operates by hedging a series of declarative statements with “sometimes” and then finally ends “What was I talking about?” The speaker ultimately loses the thread of the argument, ending on a note that feels right for the book, even as it fails to resolve anything.