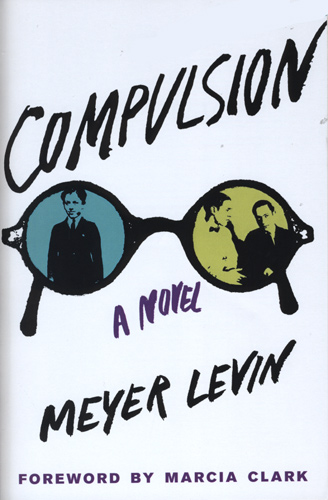

Compulsion

Meyer Levin (1905-1981) wrote novels, plays, and the Israel Haggadah for Passover still in use and in print for over 40 years. Fig Tree Books, a publisher specializing in titles relating to the American Jewish experience, recently re-issued Levin’s Compulsion, his 1956 bestseller fictionalizing the names (including his own as a reporter for The Chicago Daily News) but not the facts of the Leopold and Loeb murder trial. Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1959) and Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song (1979) followed the same author-in-the-nonfiction/novelization crime formula, producing some of their best writing. After subsequent “Crimes of the Century” involving celebrities and troubled young men both rich and poor that the media treats like celebrities, Compulsion is a reflective experience. Meyer Levin (1905-1981) wrote novels, plays, and the Israel Haggadah for Passover still in use and in print for over 40 years. Fig Tree Books, a publisher specializing in titles relating to the American Jewish experience, recently re-issued Levin’s Compulsion, his 1956 bestseller fictionalizing the names (including his own as a reporter for The Chicago Daily News) but not the facts of the Leopold and Loeb murder trial. Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1959) and Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song (1979) followed the same author-in-the-nonfiction/novelization crime formula, producing some of their best writing. After subsequent “Crimes of the Century” involving celebrities and troubled young men both rich and poor that the media treats like celebrities, Compulsion is a reflective experience.

Nathan Leopold (whom Levin renames Judd Steiner), and Richard Loeb (given the name Artie Straus) were rich, academically prodigious lovers. In 1924, they murdered 14-year-old Bobby Franks (now Paulie Kessler) testing Nietzsche’s “Superman” theory that they were superior enough get away with it. What the two Chicago collegians never anticipate is that the sophisticated wording in their ransom note and evidence left at the crime scene would give them away. Their millionaire parents hired the legendary Clarence Darrow (Jonathan Wilk), who helped them avoid the death penalty by presenting a thorough examination of Leopold/Steiner and Loeb/Kessler’s personalities—the first psych profiles ever entered as evidence. The two received life sentences. An inmate stabbed Loeb/Kessler to death in 1936. Leopold/Steiner served his sentence until 1958 when released for good behavior. He died in 1971.

This particular story of wealth and murder been told many times. Compulsion was made into a 1959 courtroom drama directed by the versatile Richard Fleischer featuring great performances by Orson Welles as Wilk and Dean Stockwell as Steiner. Nine years earlier, Alfred Hitchcock adapted Patrick Hamilton’s 1929 play Rope, a variation on the essentials of the Leopold and Loeb case. The film is not famous for its plot but for its series of long shots. Tom Kalin’s Swoon (1992) concentrated on the two’s sexual relationship. The black-and-white film is a stylish fantasy—except for the brutal scene of the death of Bobby Franks.

Compulsion opens with reporter Sid Silver (Meyer Levin) receiving news of Steiner’s release. The first section, “The Crime of Our Century,” is Silver’s account of how his two college acquaintances (the wealthy pair did not socialize with the working-class writer) plotted, carried out, and were arrested for the younger boy’s death. Despite knowing what will happen, the narrative is tense. Readers will recognize a familiar behavior pattern of vandalism, fascination with fascism, animal abuse, and possibility of being victims of sexual abuse that the two share with young men responsible for similar murder cases and their tragic modern-day equivalent, the mass shooting.

While never condoning what Kessler and Steiner did, Levin and his fictional counterpart are surprisingly sympathetic toward the two’s relationship.

Their adventure would be a continuation of their separation from the world [ . . . ] in going through it together, they would be even more as they were now, united in space and time, enclosed in an action that no one else might know of, no one else might ever share.

The book’s second half, “The Trial of the Century,” isn’t as exciting a read as its first. There is great care explaining the preparation and presentation of the case but not as interesting as the “joint personality” protagonists. However, Silver and the press’s interactions with the two is now considered a conflict of interest. Then there is the primate psychological testing used during the trial. The Jazz Age was no more tolerant of homosexuality than the 1950s America where Levin published his book. The American Psychological Society did not remove homosexuality from its list of disorders until 1975. Yet as Silver and his real-life counterpart stated, the case “served to focus the world’s attention on the inadequacy of our laws in the face of our new knowledge of the human personality and mind.”

Compulsion is a unique, first-hand account of a crime and the reverberations that continue both legally and culturally.