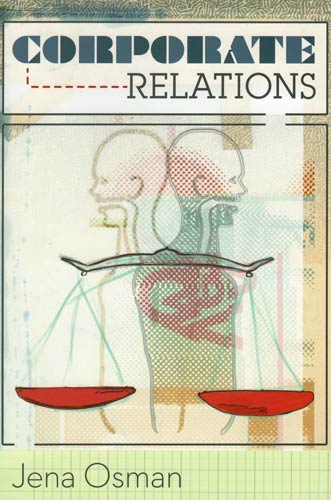

Corporate Relations

Corporate Relations opens with a series of broken analogies that illustrate the ridiculousness of the idea of corporate personhood. Even from the first section, “The Beautiful Life of Persona Ficta,” Jena Osman makes this ridiculousness plain: “it is a nightmare that Congress endorsed. mega-corporation as human group, the realm of hypothesis.” Corporate Relations opens with a series of broken analogies that illustrate the ridiculousness of the idea of corporate personhood. Even from the first section, “The Beautiful Life of Persona Ficta,” Jena Osman makes this ridiculousness plain: “it is a nightmare that Congress endorsed. mega-corporation as human group, the realm of hypothesis.”

From here, the book examines the history of corporate personhood through sections organized by their corresponding constitutional rights, rather than chronologically by legal case. Most of the poems, then, are a mix of snippets of quotes from legal proceedings, commentary, and pithy judgments (“Money is speech, and speech is protected,” for example), along with short, clear summaries of each case and its bearing on the legal development of the idea of corporate personhood in the United States.

What’s wonderful about this fragmentary presentation of information is that it leaves space for readers to interpret and reassemble the pieces more freely than a more traditional argument model would allow. Between the sections devoted to individual legal cases, additional pieces introduce other non-person entities and ideas-as-persons. Osman contemplates ventriloquist dummies, Manchurian candidates, animals, mechanical “people,” and so on, inviting broader interpretations of how “personhood” might be distinguished.

While “Mechanized Eccentric,” makes a tenuous connection between humans and machines, and never quite makes the metaphor truly resonate, the stellar “Scientific Management” makes the same comparison, but with more finesse, drawing on the body’s reliance as a whole on its individual parts, and concluding with a poignant quote from Man With A Movie Camera filmmaker Dziga Vertov: “The ‘psychological’ prevents man from being as precise as a stopwatch; it interferes with his desire for kinship with the machine.” The later “Industrial Palace” continues to build on these ideas, opening, “the body is a factory / in the workshop of the head.”

Particularly moving among the legal cases cited in the book is the “Pennsylvania Coal Company vs. Mahon” case, in which it was ruled that the coal company be allowed to continue to exercise their below-ground mining rights on land where people lived, even after the excessive mining practices in use had been shown to cause cave-ins. The book shows the Supreme Court justices grappling with how and when to treat corporations as people, and with how to make distinctions between the rights of people and the “legal fiction” of personhood as a metaphor.

This is a timely book: corporate “personhood” as a legal subject has both concrete consequences for human lives as well as abstract philosophical ones for justice in the United States. Corporate Relations treats the ideas at the heart of each legal case thoughtfully and thoroughly, without resorting to the explicit judgments that are best drawn by readers themselves. Osman’s demonstration of the far reach of ideas of “personhood” and how far back through our country’s legal history they extend shows how elastic our perceptions of justice are, and raises serious concerns about how logic can be at odds with common sense.