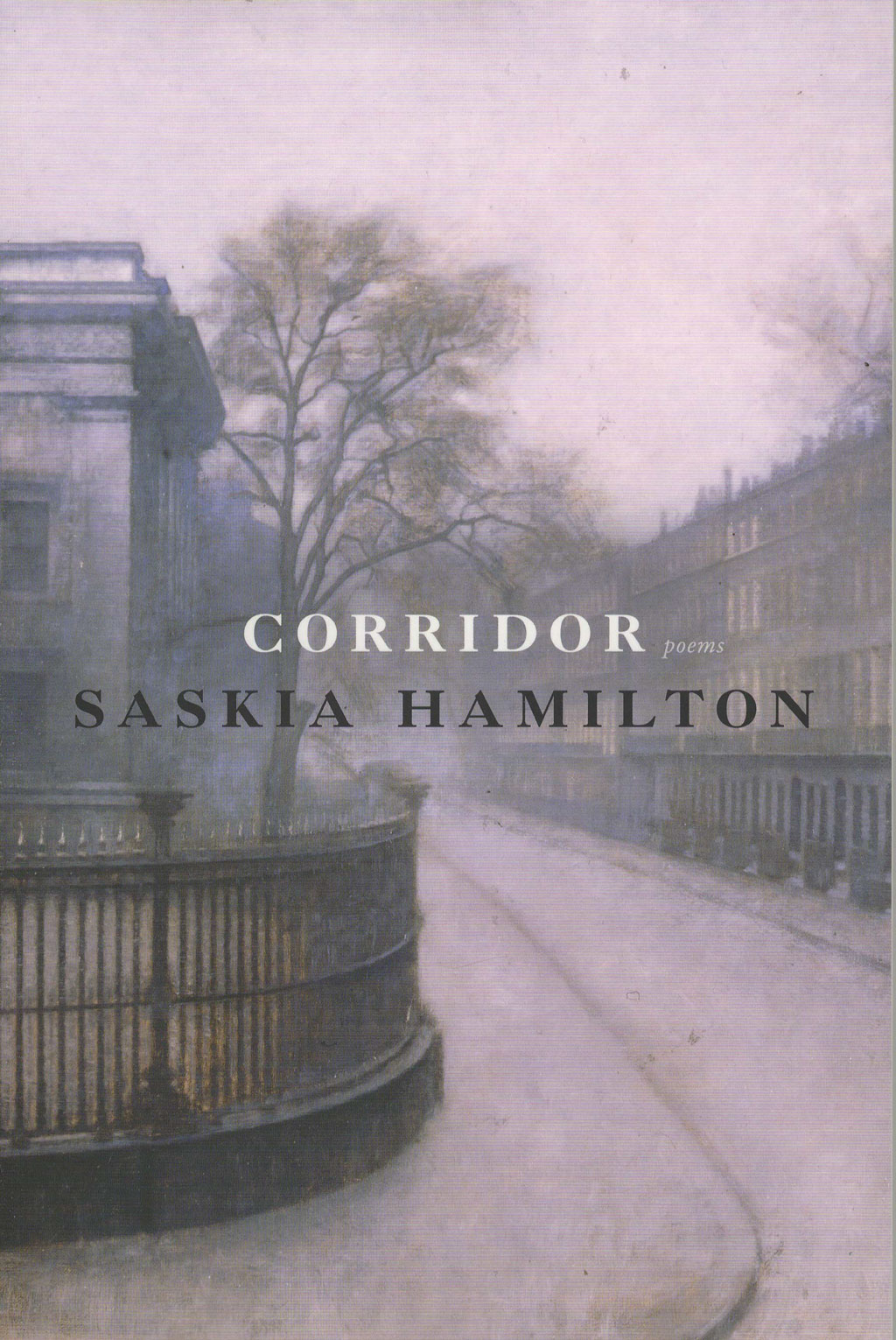

Corridor

One gets the feeling that she is always stuck in a hallway, or a “corridor.” But a corridor is not only a way of connecting rooms or railway cars; it also serves as link between two lands, and as a migratory path for birds. One gets the feeling that she is always stuck in a hallway, or a “corridor.” But a corridor is not only a way of connecting rooms or railway cars; it also serves as link between two lands, and as a migratory path for birds.

The paramount poetic force in Corridor, a book of poems by Saskia Hamilton, is foregrounded in the role of observer. In these intensely crafted poems, Hamilton explores themes of place and the delicate relationship of humans and nature. What these poems do, though, is cause the reader to slow down and absorb a row of pine trees, a house, a dog barking, at the deeply observant level of the narrator. With such detailed attention, these poems work as the corridor between speaker and recipient.

The collection opens with “Night-Jar” and Hamilton begins, “Hawking for moths at dusk: the night-jar / in the fen near the worn stone markers / of old bishopric: ceded / to sentries of the forest. . . .” The book begins in partial darkness, in the low-lying wetland of a now erased town, the office of the church closed. And since that time, the guardians of the forest now gone, the trees have begun to fall one by one. The forest, a recurring theme in Corridor, often represents an impenetrable boundary. Yet, humans have forests of their own kind, which Hamilton describes in “Spriral”: “Rows of pines, planted years ago—so many, / were you to count them on your fingers, you / would give up past a hundred span.” She goes on to say, “I’ll explain these things / some day.” This is perhaps the ethos of the book: a series of recurrent images, as if Hamilton were creating a map for readers, one with intense detail, in which she presents all of the information but refuses an analytical lens. Hamilton will not control the receipt of these poems or do any emotional work on behalf of the reader. Instead, she remains the observer, her poetic skills emanating concentration and control.

Several images recur throughout the book: a barking dog, a swarm of bees, a donkey’s ears, among many others. These repetitions connect the poems in the collection, but also complicate prior conceptions of them. The bees, for instance, are inherently living in corridors, the hive made up of small spaces through which the bees pass and fill with their honey. In “Spiral,” Hamilton briefly mentions the severe effect of moving bees only a few feet: a swarm will occur. Instead, the hives must be moved at least five miles. Later, in “An Essay on Total Colony Collapse,” we learn that the forest has become inhospitable to the bees, likely due to us humans, and now we as humans must be responsible for their care. At stake is a tenderness and severity of the human/animal condition that we so heavily rely on the dependence of each other. Without bees, we will not exist. For bees, without humans, they will not exist.

With an intense focus on image and place, when the “I” does appear, it is with great lyrical power. For example, in “En Face” Hamilton writes:

“As if it were a heuristic and yet cannot

be gainsaid,” he said. As continuous

as thought, I thought, as rain over the surface

of the earth. Facing him at the table, I caughtthe warm look of someone whose neck

I have kissed, whose ear. . .

In the first stanza, the immediate repetition of “said” and “thought,” both so close to each other, create a beat of rhythm. The pattern is then layered on by the sound similarity of “continuous” and “surface” as well as the vowel and consonant relationship between “cannot” and “caught.” Then Hamilton allows a rare moment of intimacy: “the warm look of someone whose neck / I have kissed” and we are immediately under a lyrical spell. These poems are the rare moments that allow us into a room, rather than remaining in the corridor.

The collection ends with the same title as the first poem, “Night Jar,” only this time, it is the early hour of morning. It appears that the moths have retreated to the woods “somewhere inside the edges.” How appropriate to conclude with silence and stillness, the eye of the observer still humbly present. These poems are beautifully resonant, and Corridor is the kind of collection to which I will constantly return, always finding a deeper observation—a more clear understanding.