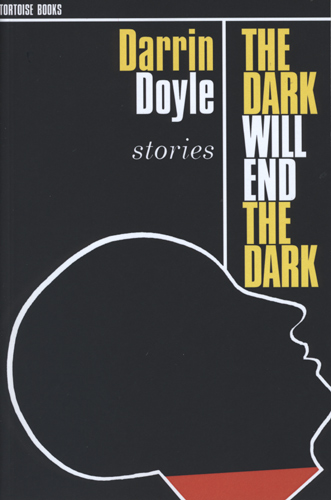

The Dark Will End the Dark

Phobia is defined, by my handy dictionary app, as “an extreme or irrational fear or aversion to something.” It’s debatable whether or not Darrin Doyle, intends to further encourage and perhaps even expand the catalog of possible phobias one might adopt in a lifetime, or whether he hopes that by delving into the darkest regions of psychic subconscious, his stories might locate the irrationality of a reader’s particular fear and give it permission to come into the light. In either case, his collection of short stories and flash fictions entitled The Dark Will End the Dark promises to satisfy the most twisted reader and the busily-untwisting reader alike.

Phobia is defined, by my handy dictionary app, as “an extreme or irrational fear or aversion to something.” It’s debatable whether or not Darrin Doyle, intends to further encourage and perhaps even expand the catalog of possible phobias one might adopt in a lifetime, or whether he hopes that by delving into the darkest regions of psychic subconscious, his stories might locate the irrationality of a reader’s particular fear and give it permission to come into the light. In either case, his collection of short stories and flash fictions entitled The Dark Will End the Dark promises to satisfy the most twisted reader and the busily-untwisting reader alike.

Doyle’s tales of severed heads, enlarged hands, uncontrolled sexual urges, cannibalistic infants, hidden rashes, drug addictions, irrepressible hiccups, and unattractive teenage girls that swallow young boys whole, is not merely gratuitously violent or repulsive. Rather, Doyle uses these physical and behavioral maladjustments to demonstrate how the body manifests its inner demons—irritating insecurities, grief, desires, fears—and the ways in which we desperately attempt to conceal what any of these manifestations might suggest about our personhood.

Why, for instance, would a woman agree to have her husband’s “dead head” sawed off then continue living with his remaining appendages, fully intact and functional, while openly enjoying romantic attention from the doctor that performed the husband’s amputation? Or, why would nearly an entire tugboat-ful of passengers throw themselves into the icy cold waters of Lake Michigan with all the drama and emotion of an apocalyptic fantasy in search of one small boy swept overboard in the fog? Did they all really take this plunge in search of the boy or were they simply caught up in a religious sort of frenzy? And what about Jim, covered from head to foot in numb sores after his divorce, for which doctors have no diagnosis, counselors no psychosomatic explanation, and dermatologists no cure?

In fact, “Sores,” Jim’s own anti-climactic tale of woe, is perhaps my favorite—not because it offers any hope-laden revelations—but precisely because it reveals, instead, our obsession with personal darkness. Jim, a man whose wife, Kathy, has left him for a woman, is slowly infested with sores. They appear one by one until finally consuming his entire body. At first, Jim endeavors to cure himself. With considerable difficulty, he stops smoking then drinking while visiting doctors, counselors, and finally a priest hoping for an explanation or a cure. Despite his efforts, the sores continue to multiply. In the meantime, the fish tank—once belonging to Kathy—is invaded with fungi, its collection of fish, like Jim, bearing a number of strange lesions, tumors, and deformities as well. In the end, the source of Jim’s ailment is never realized and he is never cured but its increased manifestation does lead him to indulge incredibly self-destructive behaviors, isolation, and a strong desire to smash the fish tank “and watch the doomed fish burst free in a rush of water, experiencing for a brief moment the wonderful horror of oxygen.”

I’m not entirely sure why, but this line—the last in the whole book—seems to sum up the mysterious nature of human weakness, desperation, and desire; the way in which we long to escape the confines of our bodies that bear witness to our hauntings begging for “oxygen,” needing to be “touched” by “another human being who (is)n’t poking or prodding” like the priest in “Sores” who shakes Jim’s diseased hand without flitching. In stories that are not too wordy nor too concise, Doyle willingly “touches” these sore spots without judging them. He simply asks his readers to consider the value of relationships, origins of faith-seeking, and behavioral motivations.

And, though fantastic, supernatural, and magical, these are not mere fairy stories or horror for horrors sake. These are human stories. While the horror-fanatic might enjoy them on a superficial level, Doyle’s stories are equally suited to individuals interested in psychology, religion, maybe even medicine. . . anyone curious about the human condition and what ails it, I suppose. It’s for the humorist—those who can laugh in the face of freaks, foot conditions, falling faces, and phobias. It’s for the lover of twisted tales, the Tim Burton-movie enthusiast, those who delight in the works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Flannery O’Connor, or Edgar Allen Poe. It’s for those willing to bring dark things into light, examine all their sides, and appreciate complexities enough to leave questions unanswered—even let them go.