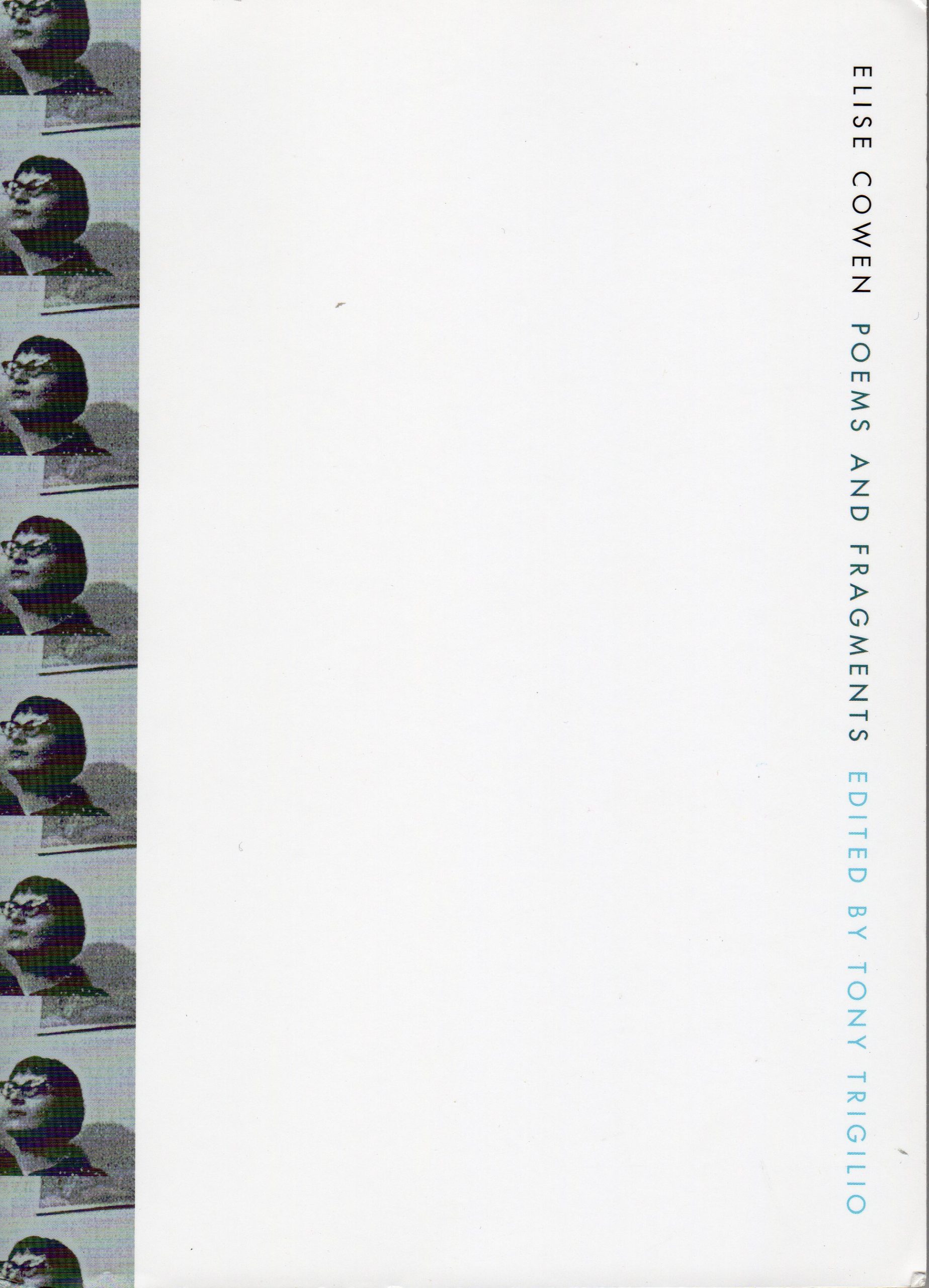

Elise Cowen

Elise Cowen is a name unlikely to ring a bell for any readers unfamiliar with the now rather legendary American literary phenomenon of the Beat Generation. Yet her writing will likely intrigue and warrant interest to a readership well beyond that demographic. Cowen’s brief life (1933-1962) proves rather remarkable for a young, unmarried woman of the era: she freely and openly explored her sexuality with multiple lovers of both sexes, including Allen Ginsberg, with whom she appears to have formed a deeper attachment, likely unreturned in kind; spent time living in both New York City and San Francisco, establishing relationships and friendships with artist communities in both cities; experimented habitually with drugs and alcohol; and dedicated herself to the pursuit of a poetic, intellectual life as much as possible all the while. Elise Cowen is a name unlikely to ring a bell for any readers unfamiliar with the now rather legendary American literary phenomenon of the Beat Generation. Yet her writing will likely intrigue and warrant interest to a readership well beyond that demographic. Cowen’s brief life (1933-1962) proves rather remarkable for a young, unmarried woman of the era: she freely and openly explored her sexuality with multiple lovers of both sexes, including Allen Ginsberg, with whom she appears to have formed a deeper attachment, likely unreturned in kind; spent time living in both New York City and San Francisco, establishing relationships and friendships with artist communities in both cities; experimented habitually with drugs and alcohol; and dedicated herself to the pursuit of a poetic, intellectual life as much as possible all the while. That her life was cut short by apparent suicide (she threw herself through a closed window at her parents’ home) speaks to the challenging personal pressures she faced having committed herself to such a life.

Samples of Cowen’s writing have previously appeared in some critical works and the anthologies Women of the Beat generation: the writers, artists, and muses at the heart of revolution (1996) compiled by Brenda Knight, A Different beat: writings by women of the Beat generation (1997) edited by Richard Peabody, and Girls who wore black: women writing the beat generation (2002) edited by Ronna C. Johnson and Nancy M. Grace. Yet the poems were always based upon Cowen’s close friend Leo Skir’s typescript of her only surviving notebook, which, as it turns out, often presents them incompletely or riddled with inaccuracies. To finally have an authoritative, complete edition of this single notebook is of indispensable service to all readers interested in the period.

The notebook contains writing in various stages. Editor Tony Trigilio notes how there are several pages with multiple poems, or fragments of poems, appearing together upon them. Some entries are crossed out and abandoned. In a few instances, unfinished letters to family and friends seem to possibly lead into the beginning of a poem instead. On occasion, Cowen has removed a page from the notebook, typed up a poem on it, and then tucked the page back in—these are clearly the strongest candidates for regarding as “finished” by Cowen. Trigilio has faithfully reproduced all of the writing, reinstating even crossed out and abandoned lines when possible, and presenting a reproduced facsimile of the odd page here and there. The few aborted letters are included in an appendix.

Despite Trigilio lodging substantial faults against Skir’s typescript, his own editorial work performed here is not without its quirks. Proclaiming he seeks to offer readers “a narrative shape,” he orders the poems in the book into four sections which he gives no reasoning for aside from this idea of instilling some idea of narrative—which he claims, “a reader might expect from any full-length collection of contemporary poetry.” Given the vast range of poetic styles and themes to be found across the landscape of contemporary poetry, Trigilio’s nod towards this opaque idea of “a narrative” is utterly arbitrary at best and at worst a significant hindrance to any reader seeking a clear understanding of the actual notebook’s contents as left by Cowen.

Especially taxing is the unfathomable absence of an index. Throughout Trigilio’s substantial notes for individual poems, he always references which other poem(s) appears upon the same notebook page, yet without an index of titles/first lines the reader is forced to pore over the Table of Contents in order to locate the other poem(s). This quickly becomes a tiresome affair. It’s ironic that Skir’s alphabetically ordered typescript would come in much handier than Trigilio’s own text when attempting to utilize Trigilio’s notes. And for all his thoroughness on a handful of specific poems, there are others where the supplied information is quite slim. For instance, the toddler “Tosh” mentioned in “Blowing Pantomime Bubbles” is quite possibly Tosh Berman, son of Wallace Berman publisher/editor of the infamous Semina and highly regarded companion of many poets and artists throughout the San Francisco Bay and Los Angeles scenes of the period. Having the possibility that the poem directly ties Cowen to Berman go overlooked is rather regrettable.

Nonetheless, only now is it possible to begin a complete and legitimate acknowledgement of Cowen’s literary potential, limited as that may be by circumstance. All of her other notebooks and papers were destroyed upon her death by neighbors as an apparent favor to her parents who seemingly looked askance towards their daughter’s lifestyle. This single notebook was luckily in the hands of Skir. Problematic as his custodianship may have proved over the years (Trigilio notes the many idiosyncratic ways in which Skir both harbored and in some circumstances walled in Cowen material from interested scholars), it’s only due to Skir’s care that we have these few complete poems and assorted fragments of Cowen’s work. Without Skir, Trigilio along with future scholars/editors and regular readers would have nothing of Cowen’s work available at all. Poems and Fragments is a testament to that love and friendship as much as it is to Trigilio’s passionate reading as both poet and scholar.