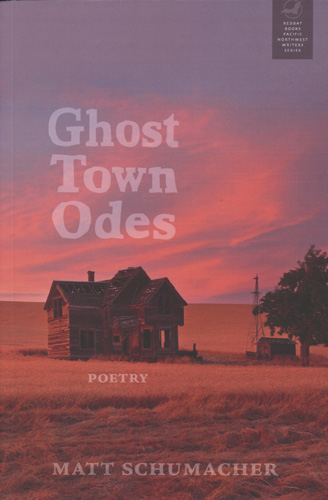

Ghost Town Odes

If you at times find yourself (as I often do) feeling a bit bummed out by the overproduction of postmodern, fragmentary poems that deliberately eschew narrative elements of storytelling, a self or subject, and/or any sense of purpose and closure, then do yourself a favor and pick up Matt Schumacher’s Ghost Town Odes. This is an ambitious book of poetry seeking to narrate tales of tribulation and triumph in the Old West, particularly in Oregon, the state the author currently calls home.

If you at times find yourself (as I often do) feeling a bit bummed out by the overproduction of postmodern, fragmentary poems that deliberately eschew narrative elements of storytelling, a self or subject, and/or any sense of purpose and closure, then do yourself a favor and pick up Matt Schumacher’s Ghost Town Odes. This is an ambitious book of poetry seeking to narrate tales of tribulation and triumph in the Old West, particularly in Oregon, the state the author currently calls home.

Schumacher’s latest book is divided into four sections: Oregon Idylls; Ghost Town Odes; Lost Letters from the West; and Pastoral with Bestiary. This expansive and inclusive collection is haunted by “Gazebos of supposed ghosts”: hard-drinking miners, gamblers, radical labor activists like Big Bill Haywood, assorted odd birds (both fowl and human) and Native Americans like Chief Joseph, who declares in one poem: “Our nations could not be bounded, banned, or trapped, / were never made for white men’s maps.” However, as a white man himself, Matt Schumacher turns out to be a very capable poetic cartographer tracing an entire region’s storied past and present.

The first section of the book (which is focused on the present time rather than the distant past) is the most successful. It starts with a lovely, lyrical poem, “Autumn Idyll,” which begins:

This October morning, my wife admired

a crimson maple on Albina,

scattering the genius of its foliage.

I’d love to have a dress that color,

but that’s impossible, she replied,

as if the tree had asked her

if she’d like to try on every leaf.

But suppose we became so acquainted

with the sun and shade today that they emblazoned

tones too bold for any wardrobe,

imbued fabric with pure revery,

unveiled sleeves that exceed the zeal

of shooting stars, stitches that dart

and dive, as alive as sparrows?

What if, just this once, autumn meant

nothing ever had to die again

The speaker’s wife shows up a few more times in other poems as well, including the sweet and humorous poem “Eden” where he wonders: “Why do these dudes who work as grocery produce clerks / often develop crushes on my wife?” He then proceeds to answer his own question by admitting that “She’s fine enough to ruffle every head of romaine lettuce.” In another poem, “Please Don’t Pick Up the Papayas,” the speaker and his wife are trying to figure out what happened to the papaya they had placed in their grocery cart, but which had vanished once they were in the checkout line. A variety of possible scenarios (all quite amusing) explaining the mysterious disappearance of the papaya are imagined, but whatever the truth might be, we learn that: “that fugitive fruit left us so surprised / we almost questioned our vegetables.”

Schumacher’s delightful and affectionate observations of contemporary life in Oregon are completely charming and authentic. In “Keeping It Weird,” he speaks of seeing a “bearded landscaper” carrying his tools in an absurdly small “child-sized red wagon— / as if William Carlos Williams’ wheelbarrow / had been hijacked by Walt Whitman.”

In the book’s second section, we discover the story behind the town of Greenhorn, OR “population 0 in 2010.” The town is named for the inexperienced greenhorns who came there from the East and struck it rich as miners, which proves “how fast the West, for all its lawless flaws” can reward some folks with luck “and turn scorn to good fortune.” Other characters in this collection aren’t as lucky, like Henry Deadmond, who is hung for the Wasco County robbery and murder of George Meek and Crawford Isabell.

Meticulously researched, Ghost Town Odes has a helpful Notes section at the back of the book providing context and historical background to some of the poems. As James Grabill writes in his blurb for the book, the author has created a “mythohistorical motherlode.” I couldn’t agree more. The scope of these poems is vast in terms of both its time period and geography, but Schumacher is incredibly skilled in making this vastness matter on an intimately human scale. In terms of form and diction, the poems in this book are all written in an unpretentious free verse style with a winning, conversational tone and an artful sprinkling of rhyme here and there.

The entire third section of the book—Lost Letters from the West—are epistolary poems mostly chronicling the violence and tragedy of life in the mid to late 1800’s. And yet, I sense a deep and abiding tenderness to Schumacher’s voice that is a bit rare today in contemporary poetry. It isn’t sentimentality, but a real and unfeigned appreciation for people and places and stories, not unlike, perhaps, some of Ted Kooser’s work. I find this quality in his poetry to be both immensely refreshing and attractive. And I bet you will too.