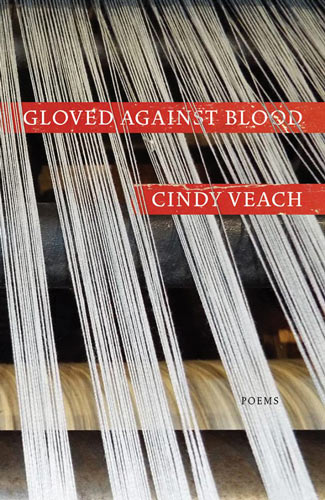

Gloved Against Blood

Gloved Against Blood by Cindy Veach is about the textile industry in the 19th century, and the people whose lives it directed, including the lives of Veach’s ancestors. Her poems bring to light the oppressing conditions the women who worked at the mills endured. She uses found poems from news and slave narratives to add a level of expose to her work. The poems also weave a history of Veach’s family, and she hints at the fact that this history, like many hardships endured, is never completely shaken but inherited, like a thimble passed down might hold a stain of blood.

Gloved Against Blood by Cindy Veach is about the textile industry in the 19th century, and the people whose lives it directed, including the lives of Veach’s ancestors. Her poems bring to light the oppressing conditions the women who worked at the mills endured. She uses found poems from news and slave narratives to add a level of expose to her work. The poems also weave a history of Veach’s family, and she hints at the fact that this history, like many hardships endured, is never completely shaken but inherited, like a thimble passed down might hold a stain of blood.

The title Gloved Against Blood brings to mind how the messy parts of our nation’s history are covered up—we don’t want the blood to soil our nice linens—but the gloves are a layer of protection for the wearer too. This title focuses on a separation, a sanitation, that is evident with so much of our country’s past.

In “How a Community of Women,” she uses the repeated syntax of “How . . . ” to form a list poem, relentless as the work was, listing her lineage involved in the work of the looms—her “French Canadian great-grandmother and great-great-aunts / toiled thirteen hours a day in the textile mills.” The verbs in this poem are violent—the “screaming starlings,” “mobbed” them, the looms “howled,” the darkness was even “ear-ringing.” This work is “close work, women’s work” passed down from woman to woman: “My mother / taught me, her mother taught her, her mother taught her.” The poem’s repetition mimics the looms, the repetitive and endless work, and the generational entrapment in the work.

One of the most riveting parts of this book were the “Lowell Cloth Narratives,” where Veach uses quotes from the “Ex-Slave Narratives” that were conducted by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in the 1930s. In this series of three poems, she uses the repeated form of “State: Arkansas Interviewee” followed by the speaker’s name. Then she uses actual quotes from the original narratives interwoven with her own poetry, lines that remain consistent among the poems. This produces an interesting effect of repetition (again, we are thinking of those looms) and heredity (the generational enslavement). The first two lines in each poem, compared side by side, starting with the first section:

I was born in slavery time—a world away

we wove we wove away. I was born in the field

under a tree. Thirteen hours a day we toiled

The second section:

“I wasn’t allowed to sat at the table—a world away

we wove we wove away. I et on the edge

of the porch with the dogs with my fingers—

And the third:

“We slaves live in de quarters—a world away

we wove we wove away. Beds made

out of wood with shuck and moss

While each story is distinct, the use of repetition with Veach’s own writing creates the feeling of a spiritual, a song sung along with the work. We see the repeated theme of separation here; they were not allowed at the table, they were born in the field, they slept on moss. Veach’s fine eye for detail allows the reader to empathize with these narratives, to feel the heat of the field, feel the coarse cloth on the skin.

Within this larger, historical narrative is a narrative of Veach’s own past, of men betraying women, leaving them to work alone. In “My Mother Tells Me Stories,” we learn of her grandfather:

who commuted

between a mistress in Montrealand the wife he got pregnant

thirteen times—once for each tripback home to Lowell.

The past cannot and should not be forgotten; this is the moral here, whether the narrative is countrywide or a family secret. In “Predators,” Veach asks:

Is it two

or three generations toforgotten—

still, the way a daughter walks, a grandson shrugs—

pure plagiarism, memory muscleturning backward forward/ not ours not theirs.

“Not ours not theirs.” And that is how Veach feels about the stories—they do not only belong to the past, yet they are not entirely ours. What they do need is to be told. Whether through the barrier of a Grandmother’s French native tongue translating to English, or the clatter of the looms, or the silencing of slavery, these narratives of abandonment, of being treated as less-than, of endless work with no voice, need to be spoken of, and Veach does that in the pages of Gloved Against Blood.