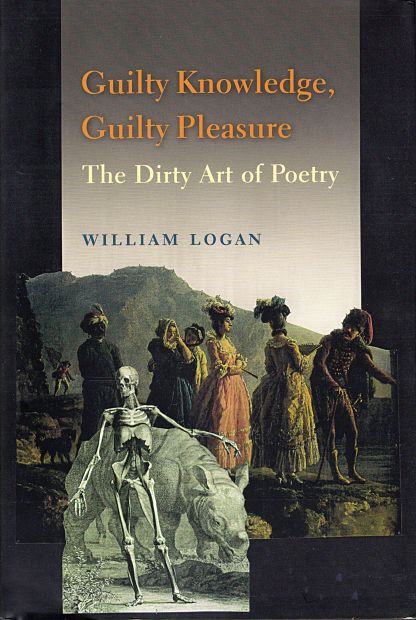

Guilty Knowledge, Guilty Pleasure

William Logan’s poetry reviews found in Guilty Knowledge, Guilty Pleasure don’t mince words. Never drab, his criticism will entertain and never bore. It doesn’t much matter whether readers agree or disagree with his judgments, as he generally delivers them with enough original panache to readily amuse all the same. He doesn’t quite reach far enough out from the borders of the poetry world to be of interest to those readers unfamiliar with poetry-at-large, but anyone with a decent background in the field, whether reading for a degree or for pleasure, will be quite well acquainted enough to follow along. William Logan’s poetry reviews found in Guilty Knowledge, Guilty Pleasure don’t mince words. Never drab, his criticism will entertain and never bore. It doesn’t much matter whether readers agree or disagree with his judgments, as he generally delivers them with enough original panache to readily amuse all the same. He doesn’t quite reach far enough out from the borders of the poetry world to be of interest to those readers unfamiliar with poetry-at-large, but anyone with a decent background in the field, whether reading for a degree or for pleasure, will be quite well acquainted enough to follow along. Or, to put it another way, even those who have read just enough to feel comfortable chatting about poetry over cocktails, yet are perhaps not quite avidly invested at a personal level, will enjoy themselves.

There is of course the question of whether or not such an audience as described above any longer even exists. These days isn’t everybody a poet and nobody a reader? As Logan writes: “Even though no one reads poetry any more, poets are still in demand.” If nothing else, the Poet-as-Personality continues to be hip and authoritative. Logan’s reviews play off just such fact. He’s courting the same level of attention, only it’s the Poet-Critic-as-Personality instead. Although to be fair, Logan’s personal “I” rarely intrudes into his criticism. And when it does, in pieces such as “A Critic’s Notebook,” he tilts in his personal comments in such a manner as achieves moments of real pop: “I have a small thing for Miriam Hopkins. It’s not the big thing I have for Barbara Stanwyck, but it’s a thing.” When Logan is intimate, it is without being intrusive. He offers just the right amount of information to earn confidence and trust.

Critics should always leave no doubt of where they stands while simultaneously providing sufficient evidence for why. The trust of readers must be earned not only by the entertaining wit of the judgment leveled, but also by example of its merit. Critical comments need the support of vested observation. Logan delivers this again and again. When at his most astute, he leaves readers assured that he’s taken more than a passing glance at the work under consideration: “Billy Collins’s method has been to borrow a dry nugget of fact or some mildly absurd observation and see how far he can go.” He identifies with what readers have found valuable in the work, offering his support for their own appreciation: “Collins’s gift was to make the poem a little odder than you expected.” He then commences with his criticism: “The problem with this new book is that the ideas are still there, but the poems have lost their sense of humor.” More often than not, the results are quite effective.

Logan’s reviews testify to the validity of his many declarations and knowledgeable one-liners, such as “truths of the bad reviewer are often more troubling than the emollient praise of critics without an axe to grind.” Here, Logan is referring to the historical reception given by reviewers of times past to now famous poets held in high regard. His point, in part, is how easy it is to go wrong as a critic when allowing one’s self to be swept up by the tide of popular opinion. Be assured that you won’t find Logan empty-handed at the grinding wheel in this collection. Whether the poet under consideration is a Nobel-winner or not, Logan says what he thinks of the work at hand. If the number of “Verse Chronicles” included (omnibus reviews wherein Logan dispatches several individual collections by numerous poets at once) feels a bit too high, he yet hits enough sharp-eyed points in the majority to prove their inclusion worthwhile. And if you missed his excellent essay full of original scholarship and insight “Elizabeth Bishop at Summer Camp” when it appeared in the Virginia Quarterly Review, Guilty Knowledge, Guilty Pleasure serves as a nice carrying case for it. Logan proves himself a prime critic of the present era.