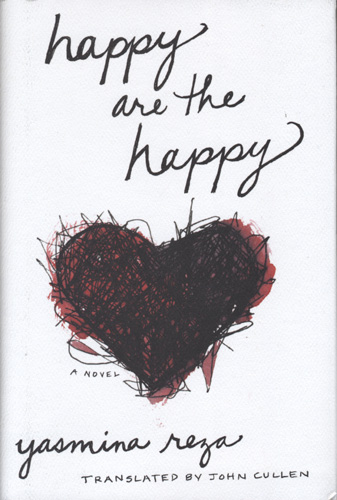

Happy Are the Happy

Theatergoers will be reminded of Yasmina Reza’s well-known plays Art and God of Carnage in this short story collection Happy Are the Happy. In spite of no paragraphing in each of the short stories, they flow with perfect dialogue, brief but definitive settings, and situations involving both humorous and sad bad behavior and embarrassment. Fiction allows Reza to exhibit her lovely style, vivid succinct descriptions, and ironic truisms and insights. Theatergoers will be reminded of Yasmina Reza’s well-known plays Art and God of Carnage in this short story collection Happy Are the Happy. In spite of no paragraphing in each of the short stories, they flow with perfect dialogue, brief but definitive settings, and situations involving both humorous and sad bad behavior and embarrassment. Fiction allows Reza to exhibit her lovely style, vivid succinct descriptions, and ironic truisms and insights.

The title’s fuller quote from Jorge Luis Borges shows better what’s inside this volume:

Happy are those who are beloved

and those who love

and those who can do without love.

Happy are the happy.

In this novel, love affairs (for which the French are known) are counterweighted by couples. For the lover:

When you meet someone, you’re not interested in his marital status. Or his sentimental condition. Sentiments are mutable and mortal. Like every earthly thing. Animals die. So do plants. Watercourses aren’t the same from one year to the next. Nothing lasts. People want to believe the opposite. They spend their lives gluing pieces back together and they call that marriage or fidelity [ . . . ] Couples disgust me. Their hypocrisy. Their smugness. [ . . . ] Their reciprocal wizening, their dusty connivance. I don’t like anything about that ambulant structure, or about the way it cruises through time taunting those who are alone.

And the couple: “The couple is the most impenetrable thing there is, even if you are part of it.” In this book, only one couple is known to be happy, calling each other “my own.” And their young son is the only happy child, in spite of how he’s embarrassing his parents:

I think he believes he’s Celine Dion, the singer. He’s always got a scarf wrapped around his neck. He doesn’t look straight at people. It’s as though he’s addressing a distant fleet, as though he’s praying on top of a rock, hoping to attract the ships he spies far out at sea, like someone in a mythic tale.

Among friends, there’s a shared ambivalence towards happiness:

Women have swiped the martyr’s role for themselves. They’ve theorized about it out loud. They groan and make people feel sorry for them. Whereas in reality, the real martyr is the man.

An advantage of fiction over playwriting is shifting perspectives. Each of the stories has the name of one character whose first person perspective dominates. Not only are the stories linked by the repetition of names, but also the intricate interrelationships of all these people. It would have been nice to have a glossary of characters and their relationships to each other at the beginning of the book, but their interweaving matches a dance like Arthur Schnitzler’s La Ronde in their coming forward and stepping back in the chapters:

We live in the illusion of repetition, like the rising and setting sun. We go to bed, we get up, we think we’re repeating the same action, but that’s not true.

Progression and a slight chronology emerge, the book starting and ending with the same characters.

Often the reader is reminded of Art (Reza’s play about three male friends arguing, and sometimes overreacting to one of them buying an expensive canvas painted white) and God of Carnage (a play about parents coming together to resolve their children’s playground fight and ending up behaving much like those children).

The two funniest stories in Happy are the Happy go over some of the same territory as the plays, the opening story from Robert Toscano’s perspective and a later one from Vincent Zawada’s. In the first story, Robert argues with his wife Odile in the food market, first over her buying unhealthy food for the children and then standing in a long line to get cheese that he doesn’t like. Robert creates a scene, escalating the situation. It’s hilarious and could have ended harmoniously, had he not spotted a woman in line laughing at him. In the later story, Vincent accompanies his mother at her oncologist’s waiting room, while she loudly proclaims who has wigs, who won’t live long, and then how she’s the doctor’s and the medical secretary’s favorite patient. Even when a gentleman sitting next to her is called first to the doctor’s office, she sees his gallantry as his being attracted to her.

Reza humorously captures in small details the realities of married life, like husbands overreacting about his wife reading when he wants to sleep after her long preparation for bed, or a place—a baby “living the first hours of her life, swaddled in her waxen room”—or a character, from his bad clothes and food, which will end in his stroke, but before that, a pigeon shitting on him. For all of its sometimes irreverent humor, this collection of Reva’s stories shows her mastery in being able to balance the funny with the insightful.