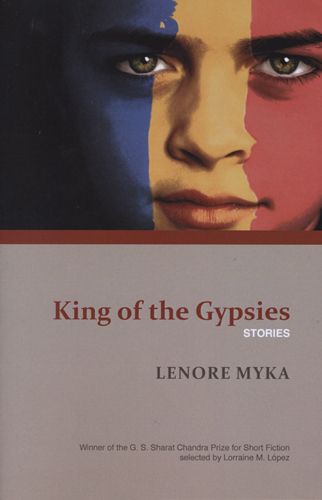

King of the Gypsies

There are linked wounded wonderers wallowing in the unsympathetic world inside the pages of this illustrious collection of short stories. In King of the Gypsies, Lenore Myka writes each story with passion and an abundance of knowledge for the Romanian culture. Her haunting tales depict the realities of abandonment and the continuous search for something better. There are linked wounded wonderers wallowing in the unsympathetic world inside the pages of this illustrious collection of short stories. In King of the Gypsies, Lenore Myka writes each story with passion and an abundance of knowledge for the Romanian culture. Her haunting tales depict the realities of abandonment and the continuous search for something better.

She does not shy her readers from the allure of false hope or the entanglements brought to those forced to live within a cruel world of sexual deviance and relentless degradation. In “Palace Girls,” for example, she lavishly illustrates an unforgiving scene in which a group of young prostitutes hang themselves, and in “National Cherry Blossom Day,” an alienated married Romanian woman embarrasses her American husband by drinking too much vodka and doing the Macarena at an important business party thrown by one of his colleagues.

In “King of the Gypsies,” the main character, Dragos, travels through life fighting bullies and searching for his mother. Myka retains this character in the story “Song of Sleep,” so readers can meet him again many years later as a young man married to an American girl.

One story that shifts from the psychological exploration of familiar banality or the uncompromising brutalities of violence (in some instances humiliation from a particular sexual perversion), and takes an almost gothic turn of Romanian folklore is “Wood Houses.” In this tale, an adopted boy in his teens becomes suspiciously aggressive and starts to show signs of a hirsute transformation.

Throughout each of these eleven stories, Myka showcases the Romanian culture by sprinkling ethnic references throughout (like sheep cheese, polinka, stuffed cabbage, salami, and numerous Romanian words). When she is not alluding to Romanian-specific tendencies, she is writing beautiful imagery, like: “The moon is out now, a fingernail clipping littering the black rug of sky.”

I found this book to be colorful and evocative. There is a common theme of emotional perseverance through an increasingly malevolent world layered within each tale. Each complex character is original and depicted with such clarity, it’s as if Myka revealed them to us through her own experiences. When I learned this was her first book, I dropped it in shock and it landed on my toe. It might have hurt if not for the empathy I felt for the suicidal prostitutes, the helpless housewife, or the lonely boy pretending to be king. This was a fascinating read, good for anyone who enjoys provocative storytelling from a gifted writer.