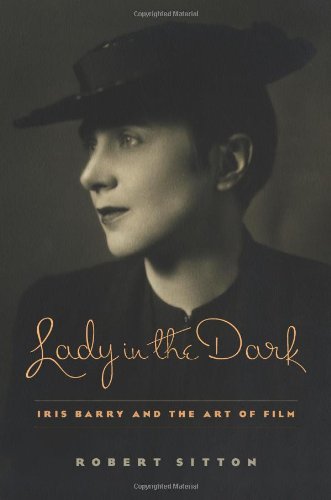

Lady in the Dark

The “moment” in Robert Sitton’s Lady in the Dark: Iris Barry and the Art of Film does not involve Ms. Barry. Over a series of formal meetings and parties, several millionaires (Nelson Rockefeller and Jock Whitney) and their talented, educated friends (architect Philip Johnson and the wealthy painter Gerald Murphy) decided to create The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). That they accomplished this during the Great Depression is miraculous. They knew society—not the types in nightclubs or their equivalent to the red carpet—could not survive without culture.

The “moment” in Robert Sitton’s Lady in the Dark: Iris Barry and the Art of Film does not involve Ms. Barry. Over a series of formal meetings and parties, several millionaires (Nelson Rockefeller and Jock Whitney) and their talented, educated friends (architect Philip Johnson and the wealthy painter Gerald Murphy) decided to create The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). That they accomplished this during the Great Depression is miraculous. They knew society—not the types in nightclubs or their equivalent to the red carpet—could not survive without culture.

Perhaps better known for the Movado watch, the Bell-47D1 Helicopter, and Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World on permanent display, MoMA regarded film as art from the beginning. Established in 1935 as The Film Library, The Museum of Modern Art’s Department of Film is regarded as the most inclusive international film collection in the United States. In 1937, the Film Library received an Honorary Oscar. Now totaling over 22,000 titles and 4 million film stills, the collection spans the entire history of film. Unlike the Library’s early days when flammable nitrate film stock was kept (and occasionally caught fire before restoring cellulose nitrate base film became a possible yet painstaking process) on museum grounds, the collection is stored offsite in Hamlin, Pennsylvania. MoMA screens approximately 700 films a year. An October 2014 retrospective honored Iris Barry.

Reading about this turbulent yet creative time is fascinating, as is the woman who played a part in it and insured part of its legacy. Iris Barry (1895–1969) was among MoMA’s first staff members, serving as film programmer, curator, librarian and department director. A published poet mentored by Ezra Pound, the movie buff found her writing niche as a film critic and a co-founder of The London Film Society. A knowledgeable movie buff and poet is uniquely qualified to provide a firsthand account of seeing Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush when released in 1925:

It was, as the programme reminds us, the children who first discovered Charlie, and while he has their clear music wherever he goes—ours too, and all of it laughter of the most celestial kind, pure laughter of joy—his supremacy is unchallenged.

Charlie Chaplin became an enthusiastic supporter of The Film Library. D.W. Griffith should have been, but did nothing but complain. His films were among the first in the Film Library. Additionally, Iris Barry’s D.W. Griffith: An American Film Master is one of the first and best studies of his filmmaking. Walt Disney was initially skeptical when Barry met him in Hollywood looking for support for The Film Library, but The Three Little Pigs was on the first program Iris scheduled for the Wadsworth Athenaeum, the museum model for MoMA.

Chaplin, the Tramp who never loses his dignity, and Disney, the studio boss remaking the world in his own chauvinistic, racist cartoon image, are opposites. Barry specialized in that type of polar programming. She also screened controversial films. Griffith was polarizing then and now. In post-World War I London, she received criticism for showing Soviet films (e.g., The Battleship Potemkin). In pre-World War II, the same thing happened when she added German films (e.g., Triumph of the Will) to the Film Library.

These accomplishments in film and museum worlds were unique and unrecognized at the time. Some of this is due to the time she lived in, but Sitton makes it clear that Barry’s life resembled a shredded screenplay. There is her misogynistic relationship with writer/artist Wyndham Lewis, the father of her two children. She left the children behind in England when she came to America with her first husband, Alan Porter. An unapologetic social climber, she left Porter for John Abbott, scion of a well-to-do family who left the stock market to join Barry at the Film Library. Abbott not only took full credit for his wife’s work, he also became MoMA’s director following the ugly firing of founding director Alfred Barr. Iris stayed on at the museum after their divorce but left in 1950 following cancer treatments. She died in France in 1969.

What else her biographer does is re-introduce this talented woman to filmgoers who read up on the industry dealings via the Internet/social media, attend festivals, and stream or own many of the films mentioned in Lady in the Dark. Who knows what Iris Barry would have thought of watching movies on a computer or phone, but she did know that MoMA’s mission would encompass “our enthusiasm for the film as a great living art yesterday, today and tomorrow has now in consequence of this progressed beyond its original bounds, far beyond.”