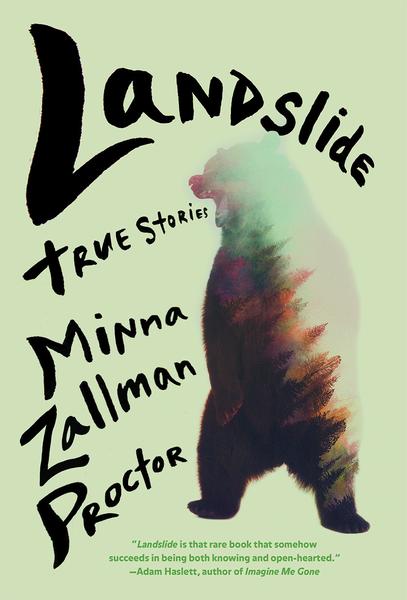

Landslide

Minna Zallman Proctor’s Landslide is a collection of “true stories” (essays, really) that focus on matters of family, familiar dysfunction, and/or love gone awry. The essays cover a wide swatch of time, with stories from Proctor’s childhood, her young adult years, and her present, and though each essay can be read separately, together they ask a question that comes up several times: Is Proctor fated to repeat her mother’s life?

Minna Zallman Proctor’s Landslide is a collection of “true stories” (essays, really) that focus on matters of family, familiar dysfunction, and/or love gone awry. The essays cover a wide swatch of time, with stories from Proctor’s childhood, her young adult years, and her present, and though each essay can be read separately, together they ask a question that comes up several times: Is Proctor fated to repeat her mother’s life? The question is asked literally as well as literarily as her therapist assuages her fears: “Doctor Wilk always argued the point, ‘You are not destined to live your mother’s life. If you’re so scared of it, just decide not to.’” However, Proctor’s astrologist, has different suggestions: “I commend you on how you’ve resolved things about yourself that you can’t change.” Both these quotes are from the title essay, which is the one that most directly tackles the idea of fate, of her mother’s slow death, of Proctor’s own insecurities with her own path—past and future—ending with her mother’s deathbed pronouncement: “Minna will never be satisfied.”

In many ways, Proctor’s lack of satisfaction is the best part of the whole book. Though living life without satisfaction can be, well, unsatisfying, in essays, a general disdain for satisfaction is quite satisfying for the readers. As a writer rethinks, reexamines, and retells their life, stories, and memories, they come to new and surprising conclusions, which the readers benefit from too. Proctor does this exceptionally well, especially in “A Mystic at Heart,” which again focuses on astrological readings, but also on her (tenuous) relationship to Judaism and her father’s regained faith in Christianity. She had previously written a book on this very subject, but found that there was more to say because her own view of faith and faithfulness had changed in the writing of that book, in the course of getting married, and then cheating on her husband, who had converted to Judaism, though she had not asked him to.

Another thing I love about Proctor’s essays is the surprising way that they move from subject to subject. In the “Mystic” essay, the subjects are braided: starting with the astrologer’s reading, then moving back and forth between that and the writing of her book, her own relationship with Judaism, her mother’s faith, etc. Since the motifs are braided, we expect each to come back and to begin to speak to each other, which they do wonderfully. However, in other essays, the thoughts and ideas move without pattern, allowing tangential associations to move us from one subject to the next, looping back on itself only when it must to bring the idea to a resolute conclusion.

Perhaps my favorite example of this is her essay “The Fool,” which starts as an analysis of her second-grade class picture, then moves to various scenes from her second-grade class, then specifically to one boy—also a Jew of Soviet descent—who made her his rival. This then, is followed with Proctor in the present, dropping her own children off at school, discussing the idea of karma, followed by analysis of children’s stories and how her own children learn that all of their stories, though there is a mighty villain, will have happy endings. But that is counterpointed with a story from Italy, where a friendly neighborhood cat is poisoned and dies miserably while other cats (and Proctor) mourn, and then Proctor’s mother gets cancer and slowly and willfully does not die, until she does. Then, it comes back to second grade, and a prank pulled on her by her rival ends up benefiting her instead of him because the teacher carefully constructs some karmic retribution. Even as I type it out, the large leaps of story and the way it comes back to itself in such sudden turns is enough to take your breath away, but Proctor is the master of such quick turns and delightfully distant juxtapositions.

In all the best essay collections, you feel like you’ve gained a new friend, but when you close the book, you remember they don’t actually know who you are and the conversation has been all in your head and in their head, but separately. That’s the sort of bittersweet emotion I had as I finished the last page, which just proves that it is the sort of book to read and reread.