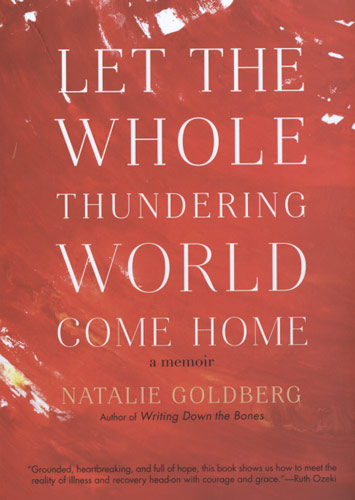

Let the Whole Thundering World Come Home

The C-word. Cancer. I’m sure if you interviewed ten people and asked them what their top three fears are, this one would make the list. And in a time in which we’re all necessarily exposed to the environmental risks posed by advances in the manufacturing industry, big agribusiness, and global warming, this fear is heightened.

The C-word. Cancer. I’m sure if you interviewed ten people and asked them what their top three fears are, this one would make the list. And in a time in which we’re all necessarily exposed to the environmental risks posed by advances in the manufacturing industry, big agribusiness, and global warming, this fear is heightened.

Before even begin this book, I felt the heartbreak, acutely aware of the irony with which a Zen Buddhist practitioner is faced: one who is astoundingly driven by the principles of peace has found herself in a situation that brings the opposite of peace. Any spiritual teacher or tradition would necessarily say that the challenges we each face in life inherently contain within them the seeds for personal growth.

It’s not surprising that Natalie Goldberg questions in the Preface of book Let the Whole Thundering World Come Home: “Could it open love? And reflection? Could I stand inside the storm, be drenched and endure, whether into life or into death?” So maybe, I thought while reading, this crisis is a point from which new learning should begin. And so I begin.

The first question we all ask is: Why? The first question we all would naturally ask, is: Why?

Twice a day I recited a loving-kindness chant and meditated on the pier [Sue] had built, jutting out into a pond full of ducks. The weather was sweater warm, the light low and still full. May I be attentive and gentle toward my own discomfort and suffering. . . . May I receive others with sympathy and understanding. . . .

When I left, I gave Sue a copy of the chant.

I tried to find the words to describe my emotions to two or three friends. Unless I talked, no one would have any idea what I was going through. The hard part was trusting that someone would understand, when I didn’t understand.

And so begins Goldberg’s quest to understand what it means to face mortality even after studying for decades in a spiritual practice that does that very same thing.

In a series of thoughtfully-crafted scenes that chronicles the journey from cancer diagnosis through treatment, readers get a glimpse of how life changes when faced with potentially terminal illness.

Cancer was teaching me how to carve out and live in a small space. I had to narrow my vision to stay on top of the drugs, the appointments, the weird changes in my body. The world shrunk to what was in front of me, to my immediate needs. Zen all along was trying to teach me to pay attention: this single sip from this cup of green tea—green tea was supposed to be a cancer preventative. This button on my shirt—unbutton it, it’s too hot. Even the screech of car brakes out the window—this, too. I’m still alive.

Then, after becoming laser focused on the small things, like signing a book with the date, stirring a cup of tea, or observing the cherries ripening on a garden tree, Goldberg learns that her partner has also been diagnosed with cancer.

So, how to cope with not just one but two illnesses?

Each section of the book begins with a different memory of visiting a gravesite. It’s an interesting cultural phenomena to pay homage to the deceased—especially the famous deceased—particularly those that are not of some relation. It’s almost like a pilgrimage. Goldberg recounts her journey: her Zen teacher Katagiri Roshi in Japan; Carson McCullers in Nyack, New York; Richard Hugo in Missoula, Montana, which she never actually found; Simone de Beauvoir in Paris; Rima Miller, a fellow cancer patient; then P.B. Shelley, John Keats, and Gregory Corso in Rome.

Just as Goldberg comes to find, so too the readers find that these graves are no different than any other graves. And for as much as people are so different, in the end, as Goldberg shows us, we are all the same. We all have our own behavioral quirks and idiosyncrasies, we all have our own worries, and we all have our own amazing talents. We even have the same fears—mostly of death and dying.

What readers learn from this memoir of the Zen practitioner and renowned writing teacher is that each and every person has their flaws, and yet, despite this, everyone on this planet matters. This understanding is the way to compassion:

I’d never used the word destiny before. What is it? A coagulation of your hunger to find a path, to find a place, to set one foot after another. To come inside out; to show your guts, everything you are made of.

If this was true about destiny, cancer was my ally on that course. It pushed me out beyond any boundary I had known. It threw me right into the pool of fear, stripped me down to animal survival. Could I face that polarity of life and death and find another place to stand?

After many treatments, both Goldberg and her partner eradicate the cancer in their bodies. The memoir ends with an indulgent stop at an ice cream shop—something the author well knows she should avoid. And while the cancer has died, the work lives on as a treatise proposing that the inertia of life, no matter how cryptic it may appear on the surface, has its own course. And that every moment is an opportunity for greater awakening, greater depth, and greater gusto.