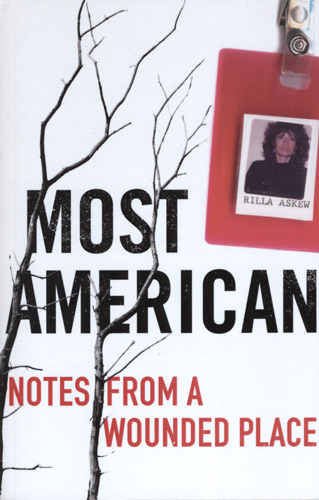

Most American

“One thing we ought not forget in this America is how our impulse to forget is so strong.” Rilla Askew, Most American

From where I sit right in Shawnee, Oklahoma, I am 41 miles from Rilla Askew, a professor at the University of Oklahoma and author of Most American: Notes From a Wounded Place, a collection of essays on race, violence, history, and Oklahoma. Six months ago, I would not have expected this proximity and would have read this novel from a distance out of curiosity, but disconnected from the Oklahoma Askew memorializes in these pages and connects to the larger American drama.

“One thing we ought not forget in this America is how our impulse to forget is so strong.” Rilla Askew, Most American

From where I sit right in Shawnee, Oklahoma, I am 41 miles from Rilla Askew, a professor at the University of Oklahoma and author of Most American: Notes From a Wounded Place, a collection of essays on race, violence, history, and Oklahoma. Six months ago, I would not have expected this proximity and would have read this novel from a distance out of curiosity, but disconnected from the Oklahoma Askew memorializes in these pages and connects to the larger American drama. Less than six months ago, however, I became Oklahoman, part of the landscape of this book and, reading as an Oklahoman, I realize how much truth-telling Askew has done, how much I am also part of what Rilla calls “a wounded place,” a state “birthed . . . in such profound hope and greed, violence and promise,” a stamp in America’s center that has come to represent “the best of what’s worse and best in us.” A memoirist, historian, and anthropologist, Askew has suspended time and distilled Americanism, everything that we think we are and ought to be, and as an American this self-awareness both grates and inspires me, horrifies, and renews my hope. I have never read a book so profound and prophetic in nature, so accurate and forgiving, forthright and kind.

Askew begins by writing of the people of Oklahoma:

Oklahomans reflect the whole of the American paradox: our selflessness and keen self-absorption, our conservatism and revolutionary impulses, our modernity and deep ingrainedness in the past. We are a generous people, compassionate, hard-working, self-sacrificing, capable of great heroism, decent. Violent. Filled with prejudice. Profoundly and pridefully independent. Sentimental.

It’s true. This is us. In 160 pages of memoir mixed with historical nonfiction, Askew reveals these qualities through our American stories of racial prejudice from the Trail of Tears to the Tulsa Race Riots; our national heroes such as Jim Foley; our great tragedies, such as the destruction of the Twin Towers and the Oklahoma City bombing; our Judeo-Christian sentiments producing misguided harm and demanding redemption; and through Askew’s own awakening from a childhood in Bartlesville, OK to young adulthood in Tulsa to an exodus and then years as an author in New York until now as a daughter returned to her Oklahoma homeland.

I am amazed by the scope of Askew’s life and vision as well as the depth she travels in her work. A skilled fictionist, Askew has managed to create narrative arch in her nonfiction. Every line and essay echoes another. The book reads like a baptism. Predominately concerned with racial issues in our nation, Askew reminds Americans how completely awash we are in these sins. She writes:

When I think of why the wounds of race won’t heal in this country, I think of the fact that for decades blacks and whites lived and worked in close proximity to one another, with most black people knowing what happened in Tulsa in 1921 and most white people entirely ignorant of it. That’s the nature of the chasm between us. That’s the legacy we’re living out, not only in Oklahoma but all over the nation, just as we’re living out our birthrights of slavery and genocide and our homegrown brand of terrorism: massacres and lynchings. We’re still living Wounded Knee and Jim Crow, still suffering the long hurt of the boarding schools, the theft of Indian children through forced adoptions. As a nation we’re all living it, but it’s only the dominant culture, the so-called normative culture, that doesn’t recognize this.

Askew connects each of these histories to her own life as she speaks of her “nebulous heritage” as part Native American and part white; her eye-opening experience as a godmother to an African American boy growing up in Brooklyn and witnessing the penalties leveled against him and his family simply exacted for the color of their skin; her pain after the televised execution of James Foley in Afghanistan, a young man who had once been her creative writing pupil at the University of Massachusetts and who represented the best in all of us; and her close proximity to domestic terror when the Murrah Building was bombed and, afterward, she wandered through the rubble, or the foreign terror of 9/11, her godson’s mother nearly suffocated by its dust. Askew herself has been personally immersed in America’s deepest tragedies, darkest secrets, and brutal awakenings.

Indeed, Askew is no stranger to immersion. Having grown up Southern Baptist, she is as familiar with the art of baptizing with words as she is with water. “I grew up on the King James Bible,” she claims, “I grew up listening to stories.” Those stories blend and collide with the Native American and African American narratives she also grew to know, creating tension—stories and narratives that informed her novels, such as The Mercy Seat, and stories that resonate with the way religion, ritual, and ceremony can be both redemptive and destructive. This immersive storytelling is perhaps why her collection of essays in Most American are so interconnected and bear the marks of religion and ritual. As I read the book (and could barely put it down), I felt caught in its stream of memory, woundedness, and redemptive cry. Askew is deeply aware of how these things flow in our blood and coincidentally reveal themselves in a variety of ways to remind us of who we really are and how we really interact with other stories.

While visiting the small Oklahoma town Medicine Creek, Askew contemplates the way that Native history emerges with white Christianity and her own Baptist upbringing as she walks through a life size nativity:

An uneasiness nicked at me. Every faux setting here, every cornily labeled pile of rocks, had a matching story in my memory, etched there by the colored drawings in my Youth Bible, confirmed in the poetic syntax of King James. The discomfort I felt then was no more than a vague apprehension, an uncomfortable sense that to make jokes about this little mini-Holy Land was also, in some inherent way, to blaspheme.

And despite the weighty nature of these essays that deal with racism, terror, religion, and historical tragedy, Askew’s prose is so pure and regenerative that, as a reader, I feel hope not despair. Most American doesn’t condemn our national sins as much as it explores our propensity to turn away from them, to be men and women of conscience who review our histories and forge a new path. In the wake of current events—racism, assault, and phobias on the rise—Askew’s book could not be more timely. This is a good time to learn about ourselves and seriously ponder whether or not we want to continue going this way.

“I’m always looking for the connectedness in things,” admits Askew in the final essay, “cohesion, some kind of invisible orchestration.” In a conversation with her friend Connie she explains, “Charles Dickens said it, . . . [w]hen people criticized all the coincidences in his novels, he said we are all so much more connected than we could ever believe.” Askew has proved this as her narratives and characters blend and borrow from one another’s wounds and histories. But she says, “modern readers won’t stand” for coincidence in a novel, in fiction, “even when it’s based on events that really happened.” “We may believe in chaos theory,” she continues, “that the flutter of a butterfly’s wings halfway around the world can change a tornado’s path in Oklahoma, but we don’t believe in coincidence.” Well, after reading this book a mere 41 miles from Askew in Oklahoma—a place I never expected to be merely six months ago—after having requested from my editor a book to review that considered the topic of racism while sending out over 200 applications to jobs all over the United States, I do believe.

Last week I walked the halls at the University of Oklahoma to speak to someone about a graduate degree, Askew’s office nearby, she already having left for Christmas break. And though I may never attend OU, our lives have touched in a strange act of coincidence. Given this connectedness and that each individual really does bear such a strong responsibility for the whole of human history and separate communities, I highly recommend—I mean highly recommend—Askew’s book. It is now one of my top favorite nonfiction works. I’m heartened by her willingness to tackle these tough topics, but with grace and full disclosure of her own complicity. Most American is beautifully written, both confronting and forgiving. Don’t start this new year without it.