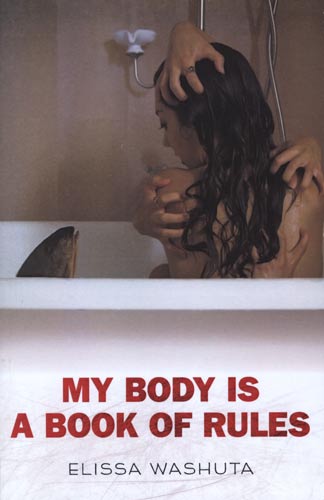

My Body is a Book of Rules

I listed My Body is a Book of Rules by Elissa Washuta as one of the books that I was currently reading online and saw that a friend of mine listed it as one of her “to-read” books. That has happened a few times but I’ve never been as happy to see it as I was for this book. It’s very possible that I feel so attached to it because I’m a 20-something girl (who still finds it weird to call herself a “woman” since that seems to imply some level of adulthood) just out of a grad school trying to figure out what to do from here. The experiences that Washuta describes aren’t all ones that I can relate to. She discusses mental illness, being raped, and being a minority in such a way that, while a reader may not be able to relate, it’s easy to empathize with her. I listed My Body is a Book of Rules by Elissa Washuta as one of the books that I was currently reading online and saw that a friend of mine listed it as one of her “to-read” books. That has happened a few times but I’ve never been as happy to see it as I was for this book. It’s very possible that I feel so attached to it because I’m a 20-something girl (who still finds it weird to call herself a “woman” since that seems to imply some level of adulthood) just out of a grad school trying to figure out what to do from here. The experiences that Washuta describes aren’t all ones that I can relate to. She discusses mental illness, being raped, and being a minority in such a way that, while a reader may not be able to relate, it’s easy to empathize with her.

Washuta’s use of humor is her biggest ally in making friends out of her readers. She discusses being raped by talking about binge watching crime shows on Netflix and comparing imagined dialogue between herself and the fictional police on television shows. This chapter didn’t make me laugh, as many of the others did, though some phrases in the beginning seemed to prompt me. What it so smartly did was make the topic of rape accessible to any reader. It’s safe to say that most people have seen a cop show at some point; it seems like they are showing on a handful of channels 24/7, so by talking about rape in this context, it gives the reader a clear, safe frame of reference. Then, in a few short sentences, Washuta upends the comfort we feel from the predictability of a typical scene between police and a victim. It becomes an interrogation with chilling comments from the “villain.” At this point in the book, the camaraderie with Washuta has been solidified, owing largely to her vibrant narration and honesty, making it impossible to not feel protective of her and angry at the entire situation. I commend her for speaking so openly and thoughtfully about things that no one could blame her for wanting to keep private. In the end, isn’t honesty the most important thing one could ask for from a memoir?

Keeping the tone balanced is never a problem. One of my favorite sections was a chapter early in the book called “Please Him” that contrasted the “commandments I picked up along the way” in Catholic school with “questions from Cosmo that started to seem important when I was twelve, eight years before I lost my virginity.” Washuta doesn’t belittle religion by putting it side-by-side with questions about sex. The section reads like a genuine muddle of enforced values and questions that might be taboo to a pre-teen were it not for the readily available pages of Cosmo. I don’t think I know a girl who hasn’t, at one point, read the quizzes or tips in an issue of Cosmo and I also don’t think I know anyone who hasn’t struggled with religion, imposed upon them by Catholic school or not.

Following the list, Washuta transitions to a discussion of virgin martyrs and saints and at one point she beautifully weaves together three of the main themes of the memoir; racial identity, sex, and religion:

When the nuns found out I was Cowlitz Indian, they offered me Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha, the Lily of the Mohawks, as a spiritual guide. I knew nothing more than that she was holy and that I was to ask her to speak to the Lord on my behalf. On prayer cards, she was rendered with deep honey skin and delicate, anglicized features. Behind her twin braids shone the circular halo that adorned the heads of all saints. She was Indian and I was Indian, so the nuns thought I would respond to her. They never told me about the smallpox scars that disfigured and half blinded her, Mohawk accusations of sorcery and promiscuity in response to her conversion, or her self-mortification practices that included whips, hair shirts, iron girdles, and beds of thorns [. . .] While Kateri’s bloodletting had once taken traditional Mohawk forms, Jesuit priests supplied all the instruments of self-ravage that a good Catholic girl might need to purify her dark Native heart.

In 1680, at the age of twenty-four, Catherine died a virgin. The old Kateri was long gone, and miraculously, so were the scars that had once marked her face, now perfectly pale.

Washuta goes on to say that she could not pray to Kateri partly because “she seemed more like one of my Native American Barbies than a saint.”

The end of My Body is a Book of Rules is so fantastic and, while it wouldn’t spoil anything, I have to stop myself from including the last paragraph or two here. It speaks so well to Elissa Washuta’s ability to combine ordinary circumstances with larger themes of life and the unknown. I finished the book rooting for her as if she was a friend. I only wish, selfishly, that the memoir had been a little longer.