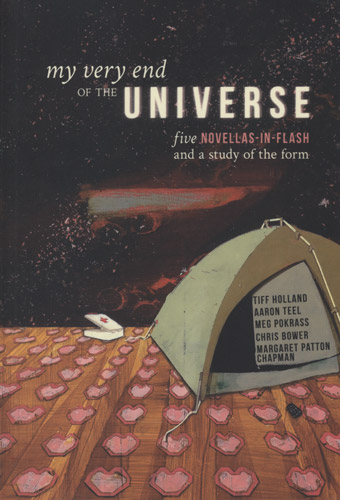

My Very End of the Universe

Five Novellas-in-Flash and a Study of the Form

Tiff Holland, Aaron Teel, Meg Pokrass, Chris Bower, Margaret Patton Chapman

November 2014

Rhonda Browning White

Editors Abigail Beckel and Kathleen Rooney have assembled, edited, and published this brilliant collection of specialized coming-of-age novellas—each one special because it is composed entirely of cohesive, yet stand-alone works of flash fiction—defined in the introduction as stories of 1,000 words or less. Helpful, informative essays by each of the five authors whose stories appear in this collection expound upon their creative process in birthing these works. Part craft-of-writing book and part novellas-in-flash collection, this unique text is both educational and entertaining: an excellent textbook or self-instructional manual on the form. Editors Abigail Beckel and Kathleen Rooney have assembled, edited, and published this brilliant collection of specialized coming-of-age novellas—each one special because it is composed entirely of cohesive, yet stand-alone works of flash fiction—defined in the introduction as stories of 1,000 words or less. Helpful, informative essays by each of the five authors whose stories appear in this collection expound upon their creative process in birthing these works. Part craft-of-writing book and part novellas-in-flash collection, this unique text is both educational and entertaining: an excellent textbook or self-instructional manual on the form.

Tiff Holland’s essay “Written in Stone: How Subject Dictates Narrative Form” discusses how flash fiction, like poetry, requires “the spark, the quick uptick, the unblurred moment.” Holland’s novella-in-flash, “Betty Superman,” is comprised of ten of these “unblurred moments,” each ending with a satisfying, sometimes surprising, ending.

Main character Betty Superman is the mother of the novella’s female narrator. The first flash, “Dragon Lady,” describes Betty in telling detail, from her physical attributes and attire to her preferences, actions, and attitudes:

What she wears: sweaters, tight over missile-silo brassieres. Pink. Yellow. Two pairs of support hose and open-toed shoes, even in winter. Estee Lauder perfume. Frills. Too much hairspray on her cotton candy hair. . . . What she says: you look like a boy. Chest out! You read too much. Just a minute, can’t you see I’m on the phone? All girls who play sports are lesbians . . . . What she calls my friends: losers, lesbians, perverts. . . . What she does: with switches, Hot Wheels tracks, hairbrushes, shoes—once with a coffee cup.

These brief, intimate, descriptions offer much more than a character sketch; Holland portrays this woman in ways we can practically see, smell, hear, and touch. It’s upon this lifelike portrait-in-words that Holland builds the stories, told by Betty’s daughter, that make up this poignant novella.

“Breaking the Pattern to Make the Pattern: Conjuring a Whole Narrative from Scraps” is Meg Pokrass’s craft essay in which she likens creating a novella-in-flash to piecing together a crazy quilt: “Working in both art forms demands an improvisational spirit regarding the creation of both content and structure . . . . Both art forms involve delving into the most unlikely places and finding pieces which, when put together, create an untraditional whole.”

Pokrass’s novella-in-flash takes its title “Here, Where We Live” from the first of twenty-two flash fiction stories about teenage Abby and her mother, who live together following her father’s death and her mother’s remarriage to a “fat, old man.” Abby’s journey from daddy’s little girl into young womanhood, while painful for any teen girl, is complicated by her father’s absence and the abusive relationship she has with her stepfather. In “Singing,” Abby dreams of her deceased father, who is critical of her rebellious attire from the grave: “He says the holes in my shoes and the inky scribbling on them ruin my looks. He says they are not cool looking, just broken. Then he says that the holes will somehow get smaller.” As readers, we recognize this as Abby’s sad, subconscious metaphor for her life, and it is this kind of imagery at which Pokrass excels throughout her novella-in-flash.

Aaron Teel tells us in his essay “A Brief Crack of Light: Mimicking Memory in the Novella-In-Flash” that “the flashes that stick are real stories that surprise with language and sharply rendered imagery, revealing some hidden or unarticulated experience in an unexpected flash of light.”

Certainly, the nineteen stories in his novella-in-flash “Shampoo Horns” are made up of this concise, sharply rendered imagery, as Teel takes us into the Seaview, Texas trailer-park poverty that is home to young Matthew:

“(I was called Cherry Tree, then, or Cherry, or Tree, or CT, but never Matthew or Matty or Matt—not even by my mother—because I was tall for my age and thin as a rail, she said, and my hair was a mess of bright red curls, only tangentially a part of my head, that refused to be corralled or put into place.)”

Cherry must become scrappy in order to survive, especially after his delinquent brother returns home to make Cherry’s life—and that of his best friend Tater Tot—a living hell. The pre-teen boys roll with the punches, literally and figuratively, juxtaposing heart-wrenching scenes with laugh-out-loud foibles in this entertaining bildungsroman.

In her craft essay “Writing the Novella-In-Flash: Maps, Secrets, and Spaces In-Between,” Margaret Patton Chapman breaks down explanation of her creative process into three parts: “Treasured Maps,” “The Space of Empty Space,” and “Silence and Danger,” describing how her novella-in-flash “Bell and Bargain” came into being.

“Bell and Bargain,” though set in the late 1890s, is nonetheless filled with modern-day problems. It relates the story of Bell, a “wished-for daughter, the youngest, the magical child,” told from Bell’s and her family members’ points of view. Bell is undeniably magical: she came out of the womb and immediately spoke her name, then began talking to—even foretelling the future of—visitors to her home. Despite, or perhaps because of, her miraculous gift, Bell feels unmoored and vulnerable, and this feeling follows her into young adulthood, where she yearns for, of all things, a corset. But “No one corseted Bell. She imagined the sharp boning, the tightness, her floating ribs bending down around her viscera, the metal and canvas enclosing her. [. . .] Most of all, she wanted armor she might fold herself into, something to protect her soft insides.”

Chris Bower tells us in his essay “A Truth Deeper than the Truth: Creating a Full Narrative from Fragments” that “Everything starts as a poem for me.” Bower includes a poem—itself a flash—as an example of inspiration for these stories. Part magical realism, part devastating truth, Bower’s “The Family Dogs: A Novella-in-Flash in Two Parts” offers eighteen flashes in young Al’s point of view, followed by one flash from his brother Matt’s viewpoint. “The Family Dogs” is perhaps the most humorous of the five novellas-in-flash, but it is nonetheless peppered with poignant and unexpected insights that make for a most satisfying end to the collection.

Take for example, the flash-fiction story “Grandma”: “Grandma used to work but not for money. She used to help draw people’s blood over at the Catholic Hospital. She came over to our house one day after work, her white blouse splattered red, and from her I learned that even volunteers can be fired.”

“We envisioned a book that was both a gripping, gratifying read and a tool for teaching and learning,” write editors Abigail Beckel and Kathleen Rooney in the introduction to My Very End of the Universe. Congratulations, ladies; your vision is now reality.