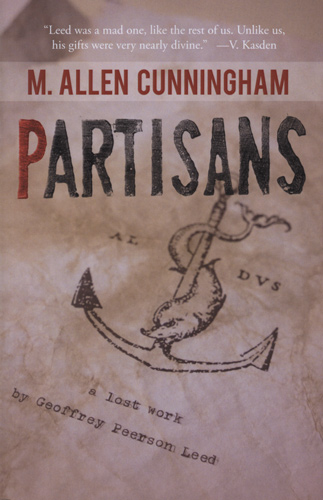

Partisans

Author Geoffrey Peerson Leed is a voice from the future. Other than a webpage issued by The Market Optimization Bureau labeling him “subversive,” there is his “lost work” Partisans. Leed too is a “ghostly neighbor” whose fate is unknown. M. Allen Cunningham is responsible for the book’s publication, presented in accordance with the author’s wishes “as indicated in manuscripts discovered after his disappearance.” Readers who favor either the political dystopias of Orwell or the zombie-apocalypse works of Max Brooks will be interested in what Leed has to say. Author Geoffrey Peerson Leed is a voice from the future. Other than a webpage issued by The Market Optimization Bureau labeling him “subversive,” there is his “lost work” Partisans. Leed too is a “ghostly neighbor” whose fate is unknown. M. Allen Cunningham is responsible for the book’s publication, presented in accordance with the author’s wishes “as indicated in manuscripts discovered after his disappearance.” Readers who favor either the political dystopias of Orwell or the zombie-apocalypse works of Max Brooks will be interested in what Leed has to say.

Partisans: A Lost Work by Geoffrey Peerson Leed is part of Atelier26’s Samizdat Series. The term “Samizdat” gives the book a sense of dangerous urgency. During the Communist era, dissidents clandestinely printed, published, and distributed censored publications (or Samizdat) throughout The Soviet Union, its satellite nations, and abroad. Vladimir Putin can choose to ignore Samizdat existed, but its importance is undeniable—and Leed’s book points to a renewal of the practice.

Partisans is an alternating triple narrative. The first is the novella “Partisans,” which follows the solider Jude as he wanders through unidentified, dangerous territory. Jude is a deserter whose role in the narrative is as observer rather than participant. While descriptions of widespread destruction are provided, details about what happened, when and why are not. Leed’s prose is out of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries:

A pilgrim now, he thought of the other pilgrims these roads had carried. They were old, old roads and those pilgrims were shadows upon the road, moving in darkness though it was day. They were uniformed and steadily walking—but not in column, not in pace.

Leed incorporates a second narrative within Partisans. Modeled on Edgar Lee Masters’s Spoon River Anthology, the dead or near-dead speak. They provide their biographies in italicized monologues immediately after Jude encounters them in their shell-shocked, skeletal, or spiritual forms. An Old Ghost tells him, “You almost look like one of us.” A Man-Woman he encounters is not surgically altered: only a father who tried in vain to save his newborn daughter by dressing like his murdered wife. “Death has no names. It is itself only,” he explains.

The soldier seeking peace and voices from the past wanting to be heard are familiar tales that Leed tells sensitively. However, the “Private Papers of G.P. Leed” gives Partisans both its true spirit and soul; it is also where M. Allen Cunningham’s presence is most felt. The third narrative is a Samizdat—a series of unconnected paragraphs, drawings, journal passages, and quotes from Leed revealing a future dependent on the Internet. Technology is the government. “We have become a people for whom ‘field’ means a white space on a screen,” laments Leed.

Leed is a fugitive on the run with a low MVR: Market Viability Rating. Because “Today everything is future,” the topics he writes about—history, the arts, printed books/libraries, individual freedom—aren’t sanctioned by the Market Optimization Bureau:

A thing is not really what we call it. Spoken language is a representation of the thing, momentarily captured in voice. Writing is, in turn, a representation of speech, durably captured in print.

Because print and analog media are deemed “irrelevant,” many artists and writers are genuinely lost. Among those who survive in name only is Joseph Brodsky, the banished Nobel laureate whose poetry first appeared in Samizdat.

Part fable, and an all-out a plea the love of good stories and the talent to tell them, Partisans: A Lost Work by Geoffrey Peerson Leed is thoughtful and, unfortunately, relevant.