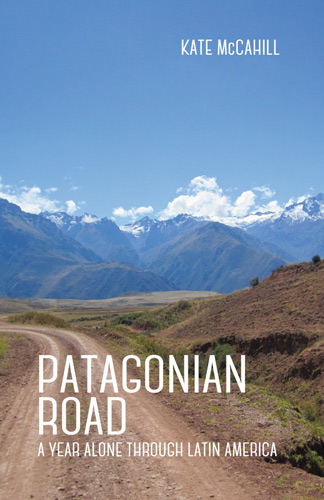

Patagonian Road

The writing of a travel memoir is, from my perspective, very much akin to the unfolding of the journey described. In spite of copious amounts of preparation, forethought, and heartfelt intent, it is all too easy to stumble along the path, or even find oneself completely lost somewhere along the way. After all, how does one successfully navigate the terrain of readers’ expectations? Are they looking for landscapes captured through lush, photographic language or a dredging of the traveler’s inner landscape? How much anthropology, history, reflection or poetic license is enough? Perhaps too much? All the while remaining true to one’s own experience.

The writing of a travel memoir is, from my perspective, very much akin to the unfolding of the journey described. In spite of copious amounts of preparation, forethought, and heartfelt intent, it is all too easy to stumble along the path, or even find oneself completely lost somewhere along the way. After all, how does one successfully navigate the terrain of readers’ expectations? Are they looking for landscapes captured through lush, photographic language or a dredging of the traveler’s inner landscape? How much anthropology, history, reflection or poetic license is enough? Perhaps too much? All the while remaining true to one’s own experience.

Within Patagonian Road, Kate McCahill approaches what just may be the ideal balance between objective and subjective elements as she recounts her year spent traveling through Latin America, guided by the route Paul Theroux described in The Old Patagonian Express. From the beginning, she frames her experience with imaginings of her grandmother’s journey to a new land, her own sense of what home means, and a longing for the partner who remains miles upon miles away. At the same time, she offers insight into the history of the places she visits and the conditions within which the people she meets live. Though the juggling of these aspects comes across a bit clumsily at the outset, by the narrative’s end, McCahill’s voice eases into a conversational tone wherein the various aspects of her experience weave together to create a tapestry of understanding and self-awareness that verges on the transcendent.

Initially, McCahill spends a great deal of time reflecting on her relationship with E—, which I found distracting in spite of its nebulous gravity. Ironically enough, what would have smoothed the edges in transitioning between her present moment experience and her ruminations on E— would have been greater insight into the relationship’s dynamics. It wasn’t necessarily that she spent too much time thinking of E—; rather, what lay behind the fretful focus in the midst of such a precious opportunity was unclear and left a number of questions as to what McCahill might be holding back. As the reader, I wanted her to trust me with the very rawness of her heart. After all, I was giving her my undivided attention and making her story a priority within my own life.

With a few exceptions, the people McCahill encounters on the road were given very little space to reveal their essence within the book. Especially when it came to those with whom she felt a romantic spark or a sense of kinship or intrigue, I craved to know more about who they were and why they mattered to her. Certainly, the encounters may have been fleeting, but it’s the idiosyncrasies, the depth of connection created by dreams and heartbreaks shared over a bottle of wine that allow for one’s humanness to be accessed, is it not? Again, I felt as though there was something important happening to which I was not privy.

As much as she keeps the reader at arm’s distance from the most significant aspects of her interactions, McCahill’s articulation of the take-aways from her journey are nothing if not poetic and serve as a catalyst for commitment on the reader’s part to her own life-altering journey. McCahill’s insight into the typical American’s lack of global perspective and the atrocities our country has facilitated throughout history piqued my interest in exploring the lessons most of us were never taught in school. Yet, it was the evolution in her understanding of time and what one truly needs that touched me most deeply, especially as her year abroad was winding up:

I wonder: How long will it take to sink back into easy laundry, to fresh clothes daily, to clean razors in a hot shower, to towels not permanently soggy? Will I get used to five or six pairs of jeans to choose from, five pairs of shoes, four handbags, two choices of perfume? Will I get used to the way perfume smells, even? Will it stop catching me on the street and making me sneeze? [ . . . ] How fast, I wonder, will I start wanting things again, things beside lunch and a room and a ticket? How long before I start to know the days, the dates, the month, the time down to the minute? How long before I’m rushing, checking buying, wishing, wanting, saving, fretting?

I’ll admit, throughout the reading of Patagonian Road, I wanted McCahill to give me so much more of herself. At the same time, I acknowledge and respect that where the road ends, it is up to the individual to share what it is she will. Be that as it may, I feel as though I owe her a debt of gratitude for inspiring me to step back from life as I know it, complete with deadlines, bottom lines, and intertwining timelines, and determine for myself whether there might be another way to navigate the second half of my life, one in which “Nothing matters more than this moment . . . and right now you have everything you need.”