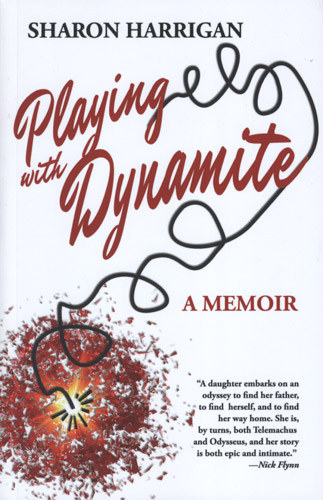

Playing with Dynamite

Parents can be strange and dichotomous creatures, and delving into their lives doesn’t always give us answers we expect. Sharon Harrigan, who teaches memoir writing at WriterHouse in Charlottesville, Virginia, discovered this when she set out to learn more about her father, Jerry. She compiled the results in her first book Playing with Dynamite: A Memoir.

Parents can be strange and dichotomous creatures, and delving into their lives doesn’t always give us answers we expect. Sharon Harrigan, who teaches memoir writing at WriterHouse in Charlottesville, Virginia, discovered this when she set out to learn more about her father, Jerry. She compiled the results in her first book Playing with Dynamite: A Memoir.

When Harrigan was seven, Jerry died when his Jeep went off the road. We also learn that as a teenager, he was helping his brother Barry and a boy named Dave use dynamite to clear a forest of tree stumps to plant new trees. As Harrigan’s Uncle Barry tells it to Harrigan:

“I made this statement: ‘If this damn thing goes off prematurely it’s going to get all three of us.’ Jerry said, real calm, ‘That’s right.’ Then he held it tighter in his hand. We got it lit and me and Dave turned our backs on it. We each took one step away, and it went off.”

Jerry didn’t step away, resulting in losing his right hand and forearm. Those events are pertinent to Harrigan’s book, Jerry’s death starting the journey she takes in trying to learn more about him.

Just as we’ve all heard stories about bad parents, Harrigan’s father fits the pattern—to an extent.

She has memories of:

Shielding my eyes as he punished our puppy by throwing him in the street. Swallowing the spoonfuls of whiskey that burned our throats because he thought it would toughen us up. Hearing him tell everyone he would take our little sister hunting instead of my older brother, because she was more of a man than Louis would ever be.

The children weren’t his only target. Jerry was so insistent that his wife Midge not gain weight, he would make her weigh herself before he gave her grocery money. Of course, there’s always another side to the story. Midge defends Jerry to their daughter saying that in those days “The way men thought of women” was different. “You can’t judge people now for doing what was normal for back then. [ . . . ] People today would call your dad a male chauvinist. But that wouldn’t be fair. Because he wasn’t. [ . . . ] He was a man of his time.”

Midge frequently said that Jerry was “the smartest man she ever met,” writes Harrigan, who also considers the positives: “He had ambitious plans. He was a man of action. He never let obstacles, like a missing hand, get in his way.” She remembers, “I was lucky to have a father who loved me beyond measure. If he didn’t, he wouldn’t have labored so hard to provide a home, safe and comfortable, for me and my family.”

Much of the book is based on conversations and interviews with relatives. In addition, it’s heavy with imagined conversations. Though she always identifies imagined passages as such, each instance made me pause and think, okay, Harrigan is imagining this next part. It had the effect of briefly interrupting the flow of narration.

Nevertheless, the overall impact of her memoir is one of liberation from her self-imposed fears, like being afraid to ask questions about her dad and believing that if she asked about him, she herself would die. She was also stuck with ideas about the lives of both parents that she later learned were untrue. Harrigan gives much thought to the concept of selective memories and the way people who remember an incident will each recall a different version of what happened. What’s more, “We live in our stories, sometimes, because it’s more comfortable than living in real life.”

Throughout the memoir, Harrigan parallels her journey to understand her father with Homer’s tale of Odysseus’s journey home in The Odyssey, a book she heard tales from as a child. Toward the end of Playing with Dynamite, she writes, “Odysseus took decades to return to Ithaca from Troy. He was sidetracked and detoured, sirened and lured, tempted and tricked. Yet he never gave up hope. He finally made it home. So have I.”

She sums up her work, saying that she and her father “have more in common than I ever knew. He crashed cars and hit his wife, but he bore within himself scars that I can only guess at, scars like the ones on the knoblike stump where his right hand used to be.” She continues, “I finally realized what playing with dynamite meant. Digging up the past, exposing family secrets to the world. Writing this book.”

With renewed media interest these days in the concept of truth, now is the perfect time to read Playing with Dynamite. Though not always pleasant reading, it shows the reality of uncovering family truths.