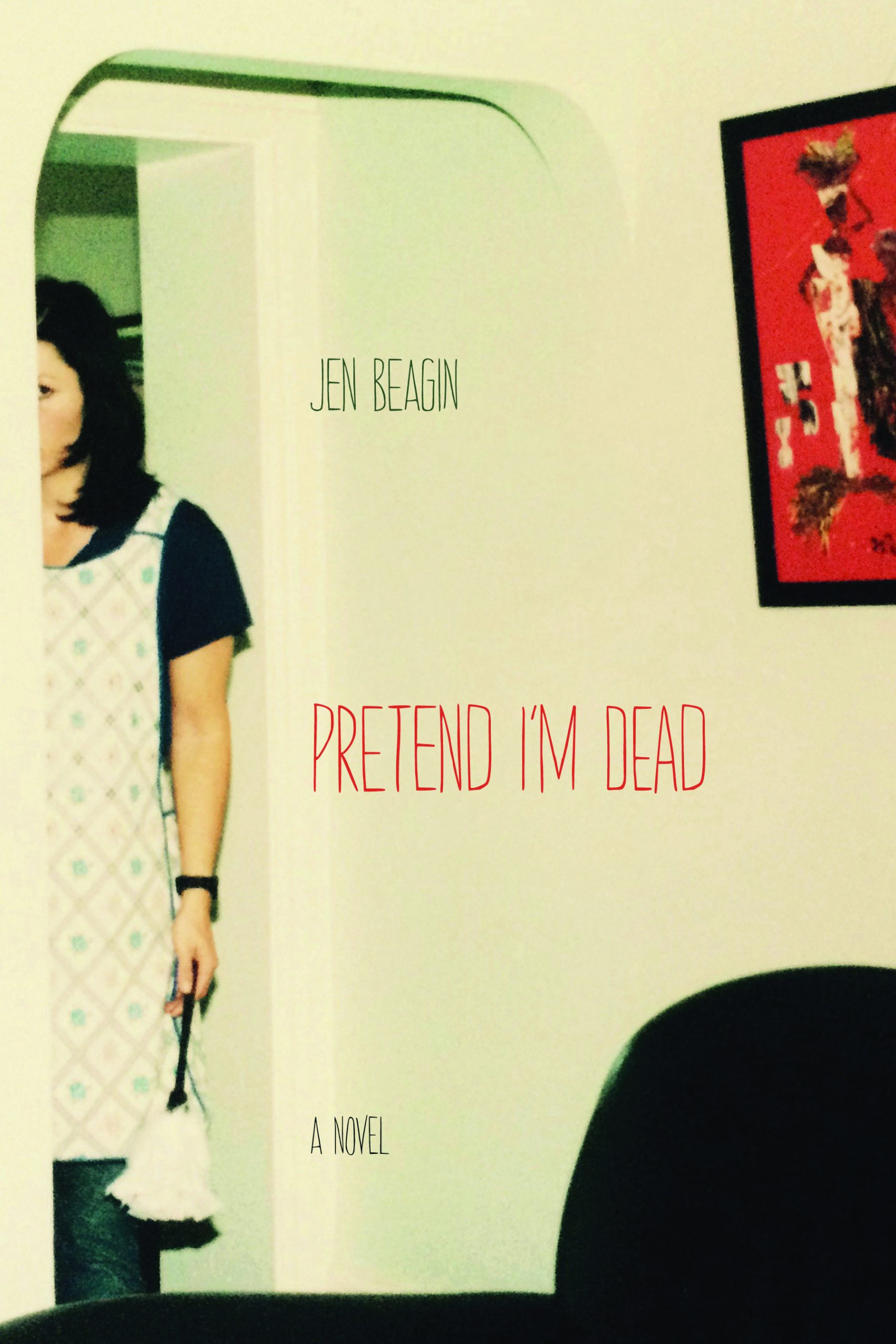

Pretend I’m Dead

Loneliness: it’s the one thing, above all things, that twenty-three-year-old Mona knows all about. That, and the proper way to clean house. In the first chapter of Jen Beagin’s Pretend I’m Dead, “Hole,” Mona is hard at work in Lowell, Massachusetts, splitting her lonesome hours between work as a self-employed housekeeper and a volunteer who provides clean needles to drug addicts. She’s particularly fond of one junkie, whom she dubs “Mr. Disgusting,” eventually falling headlong for his hopelessly fatalistic charm. Loneliness: it’s the one thing, above all things, that twenty-three-year-old Mona knows all about. That, and the proper way to clean house. In the first chapter of Jen Beagin’s Pretend I’m Dead, “Hole,” Mona is hard at work in Lowell, Massachusetts, splitting her lonesome hours between work as a self-employed housekeeper and a volunteer who provides clean needles to drug addicts. She’s particularly fond of one junkie, whom she dubs “Mr. Disgusting,” eventually falling headlong for his hopelessly fatalistic charm. “It was like dating a recent immigrant from a developing nation, or someone who’d just gotten out of jail.” When she shopped for his groceries, “He showed his thanks by silently climbing the fire escape at dawn, after his flower deliveries, and decorating her apartment with stolen hydrangeas while she slept. Easily the most romantic thing anyone had ever done for her.” It’s safe to say that Mona’s standards aren’t very high, which makes her even more endearing—in a codependent sort of way.

Her Mr. Disgusting is poetic and prolific, often scribbling in his journal or on the wall between highs. After he shoots up Mona the first time, she’s retching over the toilet—which she decides needs a good scrubbing—when she sees his handwriting scrawled next to the light switch:

If we had beans,

we could make beans and rice,

if we had rice.

Mona discovers by snooping in Mr. Disgusting’s diary that she isn’t “his favorite island,” and she realizes the relationship is doomed. Weeks pass with no word from him, and then on her twenty-fourth birthday, she receives a box from him with no return address. In it is everything she’d ever given him, along with a letter of suicidal thoughts: “My pain is ancient and I’m tired of carrying it around.” He suggests that she move to Taos, New Mexico, a town where he’d always dreamed of living, to start over.

So she does. The next chapter, “Yoko and Yoko,” finds Mona renting the smaller half of an adobo house from a New Age couple whose caring attentiveness both flatters and unnerves Mona. It also causes a bit of homesickness, and Mona finally breaks down and calls her estranged father, whom she hasn’t spoken to in ages. “His mouth was a coffin she’d spent years wanting to nail shut.” Despite the passage of time, Mona’s father hasn’t changed much: “. . . he pretended as if nothing had happened. He’d always been good at that.”

Soon Mona acquires a few new clients, and she loses herself voyeuristically, imagining what their lives must be like as she probes their secret drawers, scours beneath their beds, and discovers their private secrets. In “Henry and Zoe,” Mona fears her housekeeping client Henry might be a pedophile who’s having illicit relations with his daughter Zoe. She prowls his personal belongings for clues, finally discovering that he does indeed have a secret, but it’s far from what she’d imagined.

In the final chapter, “Betty,” Mona is hired by the title character, a practicing psychic who may actually be psychic—or perhaps psycho—to clean house. Beagin paints a vivid description of Betty McKenzie, bringing her to life so well that one might expect her to step off the page and into the room. She wore a:

low-cut green angora sweater, leopard-printed velour leggings, white, leather high-tops. The woman’s cleavage was sun damaged and livid red. Her hair was a similar red, but brighter, obviously enhanced with a rinse. Like most redheads, she probably thought she looked best in green [ . . . ] she removed her enormous sunglasses and looked Mona in the eye. [ . . . ] There was something unnatural about the woman’s eyes that Mona couldn’t put her finger on.

It isn’t merely Betty’s appearance that is eclectic, however. The woman drives a midnight-blue 1960 Cadillac convertible and lives with “several cats” in a casino-pink doublewide, the inside of which “reminded Mona of a flea market after a storm.” After several months of cleaning for Betty, the woman begins confiding in Mona, and the two develop and odd and tenuous friendship, despite the woman’s uncomfortable habit of prying into Mona’s life—past, present, and future. When Mona finds a poem Betty has penned under the woman’s nightstand, she realizes the woman may be crazier than she thought, even dangerously so.

Betty has a machete

She keeps it in her closet.

Don’t ever scorn her

Or she’ll hunt you down

And hack you

To pieces.

A brief search of Betty’s bedroom indeed uncovers the lethal tool, but Mona soon discovers that Betty’s psychic ability may be the most dangerous weapon the woman could ever wield.

Beagin’s Pretend I’m Dead, while at times heartbreakingly sad and oftentimes chuckle-aloud funny, is a brilliant study of the mental, physical, and emotional journey of a young woman who must come to terms with her abusive past before she can truly live in the present and plan for her future.