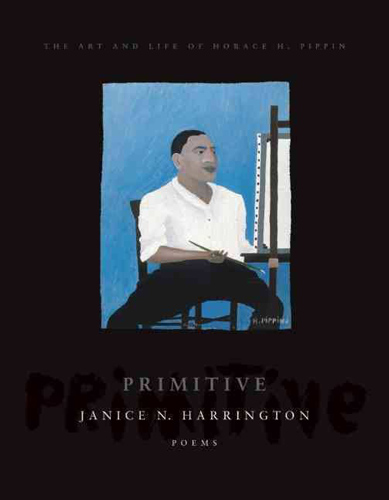

Primitive

With great erudition and a fine eye for the lyric, Janice N. Harrington’s Primitive: The Art and Life of Horace H. Pippin is an essential biographical reflection which traces the life of one of America’s most underrated painters. Horace H. Pippin, born in Pennsylvania in 1888, fought in WWI in France. After being injured by a German sniper, he returned to The United States to paint.

With great erudition and a fine eye for the lyric, Janice N. Harrington’s Primitive: The Art and Life of Horace H. Pippin is an essential biographical reflection which traces the life of one of America’s most underrated painters. Horace H. Pippin, born in Pennsylvania in 1888, fought in WWI in France. After being injured by a German sniper, he returned to The United States to paint. The critics called him “primitive,” which Harrington addresses in “A Primitive Portrait”:

He triangulates body, chair, and easel,

a confident equation: I am, he says, I am,

as if any Negro alters the canvas. Skin

as canvas stretched taut over its frame

What do we paint on it now? What did he?

In 1993, Cornel West in “Horace Pippin’s Challenge to Art Criticism” wrote: “Is a black artist like Pippin caught in a dilemma in which he may be excluded because he is black (and therefore ‘inferior’) or may be included because he is black (and therefore ‘primitive’)? This question gets at the heart of what it is to be a black artist in America.” Harrington’s poems not only engage directly with the question, but go much deeper: her poems paint a full picture of an artist’s struggle. By using verse, rather than a longform essay, Harrington illuminates Pippin’s psyche. Using Pippin’s notebooks, letters, autobiography and plenty of scholarship, Harrington takes us through the horrors of war like in “Shrapnel”:

Serrated / steel,

ballistic / trajectoriesdeath //

as small as / a splinter.Pieces /

too small / to cull,

cut free, or count.Half / men // half / metal,

perfect twentieth-century / machines.

When Pippin returns from the horrors of war, he must paint. In this section of the collection, Harrington goes deep into Pippin’s images, deciphering color and speculating on the motivations behind each work of art, as in “The Subtlety of Blue”:

whatever you wish. Maybe he wanted the viewer uncertain or

wanted to make his viewer ponder: sky. A black man altersa white canvas. He paints vapor trails, clouds, vastness.

And this is the point: he uses any damn color he chooses.

Domino players, lilies, a Victorian interior, spring flowers, a man on bench, a trapper returning home—these become the subjects of Pippin’s paintings and Harrington’s poems. The feeling that self-taught Pippin is challenging the art world, deep in debate of subject with his contemporary artists, is related in each of Harrington’s stanzas. Also, her ability to assume persona and imagine Pippin’s innermost thoughts adds a speculative and magical layer, as if the deepest kind of method acting is at work for a very important production. Harrington crawls into Pippin’s skin and gives the reader intimate access.

In March 1946, Pippin committed his wife Jennie to the Norristown State Mental Hospital. He died in July. She died two weeks after, written about in “Commitment”:

Try to imagine the two of them, a man

and a woman, a husband driving his wife

to the state hospital for the mentally ill.

He is going to commit her. Imagine the hum

of the car’s engine, the tire beating against

the road, or, if he has the window cracked

just a little for the air, imagine the wind.

The beauty and power of Harrington’s imaginings are in the details. The window is “cracked,” not open. Later in this poem, she imagines their car hitting a deer and going off the road, but “this never happened.” A better ending perhaps: husband and wife dying together in split-second accident rather than a slow painful decline. These hypothetical images add layer after insightful layer to Pippin’s life and work. They revise the standard factual biography. Poetry can go where history cannot.

Harrington’s collage of research and imagined images revisions and wraps Pippin’s life and work in a brand new light beyond the art critics, who at the time could only see race, and serves as a springboard into how poetry can enlighten history. Let’s hope Harrington continues to use her lyrical talents to explore more artists who have been smothered and wronged by America’s original sin.

“Can the reception of the work of a black artist transcend mere documentary, social pleading or exotic appeal?” —Cornel West