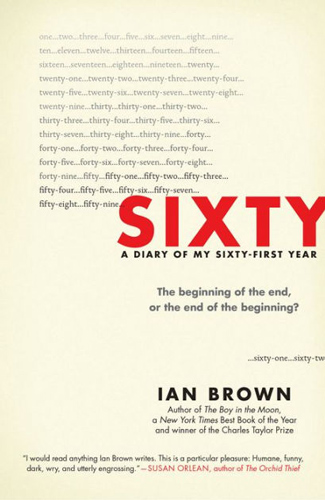

Sixty

If you’re lucky, you’ll get to experience your 60th birthday. Ian Brown did in 2014 and decided to begin a year of journaling he turned into a memoir titled, Sixty: A Diary of My Sixty-First Year. Here’s what he wrote on February 4th, his birthday: “At sixty [ . . . ] you are suddenly looking into the beginning of the end, the final frontier where you will either find the thing your heart has always sought, which you have never been able to name, or you won’t.” Then in May he wrote: “Lying in bed, I couldn’t overcome the fear that I have wasted my life, wrecked it, spoiled it.”

If you’re lucky, you’ll get to experience your 60th birthday. Ian Brown did in 2014 and decided to begin a year of journaling he turned into a memoir titled, Sixty: A Diary of My Sixty-First Year. Here’s what he wrote on February 4th, his birthday: “At sixty [ . . . ] you are suddenly looking into the beginning of the end, the final frontier where you will either find the thing your heart has always sought, which you have never been able to name, or you won’t.” Then in May he wrote: “Lying in bed, I couldn’t overcome the fear that I have wasted my life, wrecked it, spoiled it.”

Gosh, that doesn’t sound lucky. But interspersed among moments when Brown is bashed with negativity, he finds humor and a whole lot of positives in his life. He’s a roving reporter for the Canadian publication The Globe and Mail. His book, The Boy in the Moon: A Father’s Search for His Disabled Son, won three prestigious Canadian literary awards and was named one of The New York Times’ 10 best books of the year. Brown still skis, dances the tango, hikes, travels extensively, gets hungover, smokes the occasional joint, rides a bike, has a hemorrhoid (he named George), and in August 2014 wore a pair of pink pants. With the exception of naming his hemorrhoid, this might describe any adult at any age.

Perhaps Brown explains the negative/positive aspect of his book best in his preface. He had unsuccessfully searched for an “honest, interesting, readable (to say nothing of publishable) diary.” He wasn’t referring to articles and books “that celebrate seniorhood and try to reinvent aging as a new and ever-younger future. That kind of writing mostly made me want to run shrieking from the room.”

Failing to find what he was looking for, he decided to confront his aging “and keep track, at even the most mundane daily level, of the train coming straight at us.” His wife Johanna, children, a brother and twin sisters all figure into the telling. His son Walker, a young adult today, is the boy he wrote about in his prize-winning book noted above. Wife Johanna is eight years younger than Brown. “We like each other,” he writes, “We seem to think we have some duty to stay together—not for the children, but for the idea of being together. [ . . . ] And of course the prospect of starting over is daunting, I suspect, for both of us—financially disastrous, for starters, but also frightening.”

Brown notes that he’s “obsessed with the physiology of aging,” and bears this out by quoting numerous studies and statistics. Did you know, for instance, that “body functions begin to decline at the age of thirty,” or that a study in Scotland concluded that “the state of your brain in later life depends on how healthy and active your brain was when you were eleven. I’m not making this up,” he writes.

As we learn about Brown’s work and travels and people he’s known, he lists each person’s age. Some of the most entertaining passages concern celebrities and how he compares them to himself. “Stevie Wonder could be seventy, or thirty-five. He’s sixty-four. Not comparable.” “Richard Branson is sixty-four too, and looks younger, but he is worth billions, and so I don’t really count him as a real person.” Some of his comparisons are less charitable: “[ . . . ] Dr. Phil, aka Dr. Phil McGraw, is sixty. He looks like a well-tanned hedgehog.” Brown pegs “David Hasselhoff, from Baywatch (who looks twelve or ninety, depending on the angle).”

In November, toward the end of his diary he observes:

After sixty, the pressure to conform, to behave, to be a polite and respectable, ‘wise,’ even ‘cute’ human being without any troubling signs of humanity [ . . . ] is unending; our obedience is the price society wants for paying attention to us, for not shunting us off to the end-of-life stockyards.

Then on his 61st birthday, he has “the feeling I will barely notice my age until I come braking fast on sixty-five, the next official cliffside drop-off point. In any event, Christie Brinkley and I are still exactly the same age.”

Though I found some of his diary a little disheartening, Brown relates the ups and downs of his year of reckoning without shying away from health problems, societal judgments, and the mixed blessings of his life and year. Take a look at Sixty: A Diary of My Sixty-First Year to get this man’s perspective on aging.