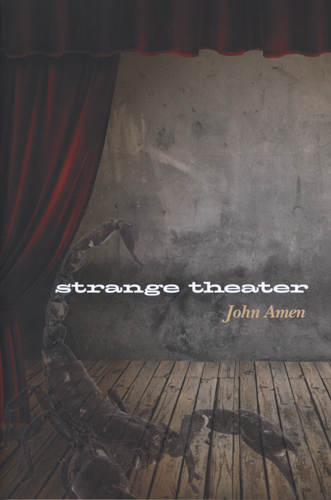

Strange Theater

Strange Theater brings us a reality where words can deposit you, drop you off, let you move struck by what you know, yet cannot quite believe (this is where we are at?). John Amen is in conversation with us. There is a we, and we have come to a turning point, we of this culture, we of this species, not knowing what we thought we were: Strange Theater brings us a reality where words can deposit you, drop you off, let you move struck by what you know, yet cannot quite believe (this is where we are at?). John Amen is in conversation with us. There is a we, and we have come to a turning point, we of this culture, we of this species, not knowing what we thought we were:

a stooping titan whose features even now

grow unfamiliar in the gloaming

who before his own failing eyes

hath become a stranger

The poet is experiencing the big picture as his/our own, our time here “a passing”:

XY hurtles from his swing & tumbles to the earth, [ . . . ] He kills his first victim by knife, his second by rope, etc., [ . . . ] (he never considered what he’s doing to constitute murder). [ . . . ] vaulting over it to the thin ledge [ . . . ] face-first, to the concrete below. He doesn’t leave a note; he’s never connected to the murders [ . . . ] & the fate of earth, galaxy, universe, continues to unfold, . . .

The poems bring us into a communal space and the individual is strung between self and others, neither distinct as to ego or roles, the voice a shared confluence. This beginning of the twenty-first century has become tenuous. We no longer know how frail or strong we are as we face what is here, let loose by our own being and actions, and reality itself provides no way forward (like it used to, when we had anthropocentric certainty). Language here mirrors our “too aware” awareness.

The poems are a narrative of sorts, a narrative about not having a narrative, a narrative about a world that doesn’t have a narrative we can comfortably recognize. The flights of words reflect the fluidity of our new self (selves), “the eyes staring back at you / as you primp or pray [ . . . ]. I try to recall / of course I can’t / how without a word / I became a stranger to myself . . . .”

Amen writes the fissure that has come, as present as a dark obelisk. What can we glean from such a line-up of words using a narrative form in conversation that shows we have become a self that is in parts and is as thin as the culture that has produced it (us)? “I’ve always been in love / with who I think I am.” Words are porous, atomized . . . it’s just not what it used to be: the words have become mere signs, armatures, and we understand, curled in our gut, the old meaning has fled. The hanger remains, but not the clothes on it.

What do we think? What can we think . . . about where we are now? Narrative form guarantees no meaning even if the story is cogent. Not only us, what we have wrought by our own hand, but the ineffable, “now & then & later / the heterogeneities congeal / into one indestructible/indivisible moment / you call it god I call it / the terror.” Somehow we have become open as everything, our eyes, we, us, we are awake, awake and full-tilt looking on . . . have we become heroes capable of looking straight into the void? We “abandoned one riddle for another . . . .” But we do what we must if we are to go on: “I can only accept to the extent / that I first resist / so I tell myself please / resist.”

The voice of these poems are what we know tucked along the untenable hollow of our presence. Language has wings with which we have always taken the unknowable flight, and Amen used them.