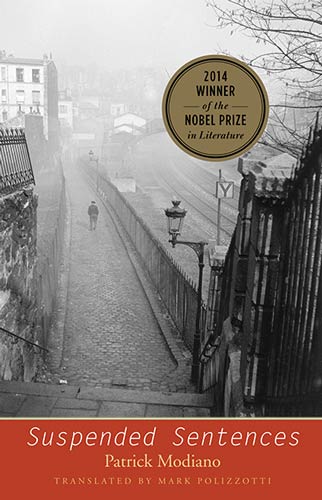

Suspended Sentences

Literary Nobel Laureates are not known for readability and popularity, yet the novels of 2014 winner Patrick Modiano (also winner of Prix Concourt and Prix MondialCino Del Duca for lifetime achievement) are easy to read and popular. His novels are short with short prose pages. Plus he recreates atmospheric noir settings, such as eerie dark abandoned castles or noble estates, and the characters he introduces are ever mysterious. His narrator, mostly unnamed and a persona for him, is constantly reminded of the past and wants to go back to understand it. Literary Nobel Laureates are not known for readability and popularity, yet the novels of 2014 winner Patrick Modiano (also winner of Prix Concourt and Prix MondialCino Del Duca for lifetime achievement) are easy to read and popular. His novels are short with short prose pages. Plus he recreates atmospheric noir settings, such as eerie dark abandoned castles or noble estates, and the characters he introduces are ever mysterious. His narrator, mostly unnamed and a persona for him, is constantly reminded of the past and wants to go back to understand it. With only flickers of real historical references, his era is Vichy Paris/WWII, so that his fans are likely readers who lived through that time. The Nobel Committee expressed the reason for their choice: “the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies and uncovered the life-world of the occupation.” Add to that the French love of unsolved mysteries that tantalize with meaning or philosophy—think of the movie Caché.

With the reissue of his novels after the Nobel, each offers a different mystery. In “Missing Person it’s the narrator’s own identity, which has somehow been lost during the war; in Out of the Dark it’s a mysterious woman, Jacqueline, he’s attached to.

The three novellas in the more recent collection Suspended Sentences offer other mysteries. In the first “Afterimage” the young narrator, in helping a famous photographer organize his work, wonders about him. In the title novella, “Suspended Sentences,” the child narrator is left by his parents with friends who, like his father, drift in and out of his life. He gets glimmers of what these people are doing, which result in their imprisonment. (And Modiano is wonderful at recreating a child’s perspective on an adult world, humorous in its misconceptions.) “Flowers of Ruins” starts with the mystery of a young married couple’s possible suicide, but then expands to other characters who might have been companions to the pair (one with multiple names and disguises) before their bloody end. Finally it expands to the narrator’s own life as he recalls a different version of the Jacqueline story from Out of the Dark.

Even with clearly autobiographical events—the narrator a budding writer, Modiano’s distant parents, and the loss of his younger brother—some are muddled: was he thrown out of school or did he leave of his own volition to wander the streets of Paris? Nothing and no one is certain, even when places are precisely described, as in “Flowers of Ruins”:

I’m racking my brain to remember as many details as I can. It was at 19 Boulevard Raspail. In 1965. A grand piano at the very back of the room. The sofa and the two armchairs were made of the same black leather. The coffee table of chrome-plated metal. A name like Devez or Duvelz. The scar on the cheek. The unbuttoned blouse. A very bright light as if from a projector, or rather a flashlight. It lights only a portion of the scene, an isolated instant, leaving the rest in shadow. We will never know what happened next or who those two people really were.

Mysteries abound, especially when the narrator, from very few details, imagines or dreams what could have happened. He either never asks the questions, which would solve the mystery, or the person being questioned doesn’t answer. People remain strangers as they would sharing a restaurant table. Ultimately, neighborhoods and people he knew as a child disappear, which makes for “nothing” (a repeated word). At the end, “We keep on waiting for nothing.”

Time is confused as well: “In the late-afternoon light, it seemed to me that the years become conflated and time transparent.”

We don’t even know the narrator, except for the appeal of his life wandering the streets of Paris, an appeal that reaches to the reader:

But then, the gates of Paris were all in vanishing perspectives; the city gradually loosened its grip and faded into barren lots. And one could still believe that adventure lay right around every street corner.

In any case, the mystery must go on for its edginess, tension, even danger. At the same time, we are following the way the mind works—the past recalled by seemingly unrelated present details. Characters pile up and may divert from the original mystery but also may relate to it. It’s a convoluted progress of altering events.

The reader needs to buy into unresolved mystery. It does, after all, yield the truth that we cannot truly know another person or past events. Modiano’s books offer the nostalgic geography of loss.

But they are similar to the point of repetition. The reader might choose just one. For me, Missing Person was more controlled, had more eerie nightscapes of elegant estates as well as offering the endless fascination of discovering one’s identity, piece by piece. The weakness in Modiano’s novels involves characters, of necessity always sketchy—even with distinctive physical details—since the people are mysterious. Even in emotional situations—encountering his father, discovering what might have happened to his disappeared wife and being attracted to Jacqueline—the narrator seems bloodless. However, what reader does not like exploring the past for its meaning?