Tells of the Crackling

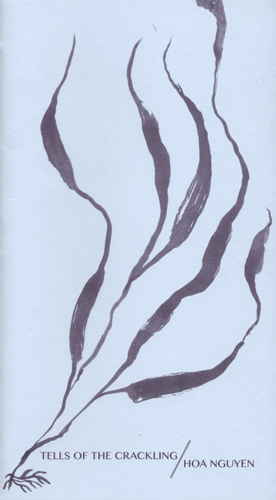

I have always found Hoa Nguyen’s poems surprisingly comfortable to inhabit, considering the challenges they can offer, and Tells of the Crackling, a lovely little hand-stitched chapbook from Ugly Duckling Presse, is no different. Spare, elliptical—not exactly breezy, but roomy—these poems are a bit like walking over a brick path gone uneven from the undergrowth, fresh and tentative vegetal shoots sending trajectories of thought this way and that. Indeed, there is a dual “crackling” of both spring and autumn that characterize the poems, a light and almost sickly feel, a mind not quite right, the sound of tea being made in the background. I have always found Hoa Nguyen’s poems surprisingly comfortable to inhabit, considering the challenges they can offer, and Tells of the Crackling, a lovely little hand-stitched chapbook from Ugly Duckling Presse, is no different. Spare, elliptical—not exactly breezy, but roomy—these poems are a bit like walking over a brick path gone uneven from the undergrowth, fresh and tentative vegetal shoots sending trajectories of thought this way and that. Indeed, there is a dual “crackling” of both spring and autumn that characterize the poems, a light and almost sickly feel, a mind not quite right, the sound of tea being made in the background. Here are a few lines from the opening poem “Autumn 2012 Poem”:

Time like a ball and elastic

so I can stop burning the pots

wondering yes electric stove

She is her but I don’t rem

ember remember

the ashes I obsess She said

The irregular spacing and starts and restarts (“rem / ember remember”) are techniques we find throughout, and one can certainly think right away that this is a form of erasure, that a fuller narrative is back in the invisibilities of the room. Nguyen even gives us a bit of an ars poetica for this a few pages later in “My Green”: “punctuated shredded parts / the absent words / that tell you how / to sing the impossible / song.”

But to give these poems this sort of reading (as a form of erasure) is perhaps to wrestle them into a fashion that doesn’t quiet suit them. There is, of course, art to this, a poetics, but it belies something more personal and psychologically evocative. The repetitions, restarts, irregular spacing—these work as a kind of stuttering, with intelligences, impressions, and emotions flaring up as the words find their pathways:

I forgot why I wept

last night It was children

& dark I wear a silk

camisole do I

and a cheap black

tunic

Here is a brown pastel scribble

and should be shamed

Can glitter? I show

off all the time

And at the end of these lines, from the poem “To Seek,” we get another ars poetica: “I want the root of the words / not the fucking use / made purposed and stupid.” Few poets can so effectively evoke the mind as an organ of thought: imperfect, messy, juggling several things simultaneously, both logical and emotional. There are special moments in these poems when that juggling feels especially breathless, and we get resistant but evocative little paintings of cognitive moments, like this, the ending of “The Whiteboard”:

All the time: goodbye to this

Extinguish This extinguish

in the wrongest of places

You eat the moon

suns or chase the chase here

Bell Bell mortal

There is a balance, staggered down the lines, of different territories. “Time,” “goodbye,” “extinguish,” “chase,” and “mortal,” all mark out one territory, then “moon,” “suns,” and “bell” mark out another. The two are folded, overlapping each other, and right at their juncture, in that center couplet, we get the emotional stitch, the “wrongest of places.” The intuited narrative is, maybe, an untimely death, but it is made startling, somewhat foreign, or “root,” by Nguyen’s approach. We are left feeling uneasy and unsure, and that’s the point.

The tics of stuttering, repetition, and the breaking and reassembly of words all suggest a strong sense for the material and sonic qualities of language, and I would ultimately say that Nguyen organizes her poems by these qualities. She even gives us a few sonnets. In one of them, “Sonnet for Mimir’s Head,” we get the title of the chapbook:

I was the song pip in the tree

is a sustaining stutter star

inside your head resides there

tells of the crackling Hung

“Tree”/“there” and “star”/“hung” ostensibly provide our As and Bs in the rhyming scheme, and no doubt they are deeply slanted, but, to my ear, they still work, and they play perfectly into the same openness and resonance of image and trajectory of thought we’ve been discussing thus far. In other places, Nguyen employs something of the opposite: rhyming schemes that are aggressively tight, flirting with homophonic constructions (that echo the straight ahead repetition we’ve already seen). Here is a wonderfully effective progression from “Mekong I”:

How to strand become

mangroves stranded

and braid your oiled hair

Vivid swoops that coiled around

a mouth and canal there

Row from here to there

“Strand,” “stranded”; “braid,” “oiled,” “coiled”; “swoops,” “around,” “mouth,” “row”; “here,” “there”—it’s virtuosic without being refined, and that is, in the end, the best thing I like about these poems. Every read offers something new to think about, new puzzles you didn’t see before, new sonic patterns, imagistic resonances, and logical progressions, but for as much art as is here the poems also feel intimate and casual, like we are in the living room with Nguyen. We feel the work of craft in the lines, of poetry as psychological index, a print of the mind’s habits and pursuits. The lovely, handmade production and simple design fit this sense wonderfully. Holding it in my hands and reading its lines, I can only feel as though the poet has given this gift to me directly.