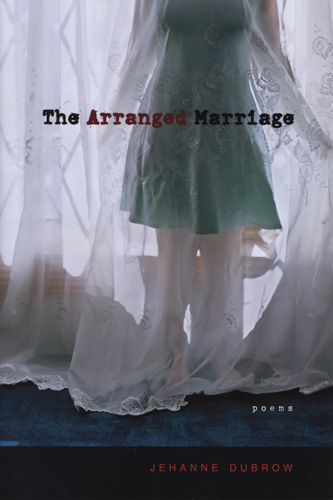

The Arranged Marriage

According to my 1971 two-volume compact Oxford English Dictionary, trauma refers to “a wound, or external bodily injury in general; also the condition caused by this.” This imprecise definition, however, has been narrowed over time and refers more specifically to the emotional shock that follows a deeply distressing or disturbing experience. This shock may last indefinitely and can feel like a reoccurring visitation of the event that caused it in the first place. Jehanne Dubrow’s collection of prose poems titled The Arranged Marriage not only addresses the emotional complexities of arranged marriages, as well as the more specific situation of that marriage including Jewish tradition and life in Central America, but also trauma by its more modern definition. According to my 1971 two-volume compact Oxford English Dictionary, trauma refers to “a wound, or external bodily injury in general; also the condition caused by this.” This imprecise definition, however, has been narrowed over time and refers more specifically to the emotional shock that follows a deeply distressing or disturbing experience. This shock may last indefinitely and can feel like a reoccurring visitation of the event that caused it in the first place. Jehanne Dubrow’s collection of prose poems titled The Arranged Marriage not only addresses the emotional complexities of arranged marriages, as well as the more specific situation of that marriage including Jewish tradition and life in Central America, but also trauma by its more modern definition. Dubrow’s poetry discerns trauma through repetition, fractured memory, re-telling, and re-visitation of her then 20-year-old mother’s experience being held hostage at knife-point for 24 hours. As the poetry shows through its jumbled narrative, the resultant long-term emotional shock from this experience was further aggravated by the forced intimacy of her mother’s arranged marriage, a marriage that inevitably ended in divorce.

Typically a formalist, Dubrow chose to write this collection as prose poems based on interviews she conducted with her mother. In fact, Dubrow’s mother was deeply involved with this collection having contributed to editorial decisions about individual lines and narrative arrangement. Her involvement likely affects the quality of the work in that, as a reader, I felt invited into every terrifying memory—I relived the trauma with Dubrow’s mother. This trauma is often delivered as a version of the experience such as in “Doubt” in which “[h]is hands were paperweights, heavy enough / to hold a woman down. Sit there, he said, Now / speak. . .” or as in “Still Life” in which the traumatic experience is reflected in a painting of a “chair on / its side, like a body kicked. A chain dangling / from the front door.” And then there’s “Makeshift Bandage” in which “[t]he attacker is bleeding where she bit him. So/she ties a towel to his hand. . .” and also “The Woman in the Grocery Store” which literally begins:

In one version of the story, she’s third person.

And he’s attacker who held her for a day. Never

name. Not even last name first, as in official

document, as in report in triplicate. Right now,

she’s running through the frozen foods [ . . . ]

Sometimes, the trauma is reflected in the story that unfolds between husband and wife, in the forced element of their marital intimacy. For instance, “House of a Small Dictatorship” reads:

Look, there’s the woman he married and there

his daughter’s porcelain face.And before the soup, a glass of limonda to

whet the tongue like a knife.Sometimes he takes his coffee on the terrace.

Sometimes he takes his wife.

And “Portrait of My Mother’s First Husband, with Faberge Objects” compares the husband to the captor with:

I want to say he isn’t bad—that every story

needs a man who lifts an egg against the light

to find the hairline crack. Already his fingers

have found a flaw in the enamel, and the clasp

that doesn’t always catch

Over and over again, with linguistic precision and narrative constraint, Dubrow’s prose poems reintroduce the reader to the emotional conflicts created by violent acts and forced intimacy; Dubrow is creative genius reflected in each poem’s power as both an individual snapshot and collaborative piece of what Claudia Rankine has deemed “a mosaic of assault.”

As a victim of past traumatic events, I was profoundly moved by Dubrow’s portrayal of its psychological and emotional aftermath. However, even readers who have not experienced physical violence or forced situations will undoubtedly appreciate Dubrow’s fifth collection of poetry. Intelligent and curious readers will be drawn to its story within a story approach, especially given that even its fiction is not fiction. Everything presented is authentic—it happened—even when the memory is partly fabricated, doubtful, and precarious. However, my favorite poem in this collection speaks with perfect clarity; it is “Dubrovnik” in which Dubrow reminisces over a photograph:

All

I can think is perhaps I climbed a stairwell

carved in stone, ten years before the city was

besieged, that Dubrovnik did exist as walls

around walls around walls—and that perhaps

my mother once stood on a rocky beach, like a

beautiful city untouched at the vulnerable

points.