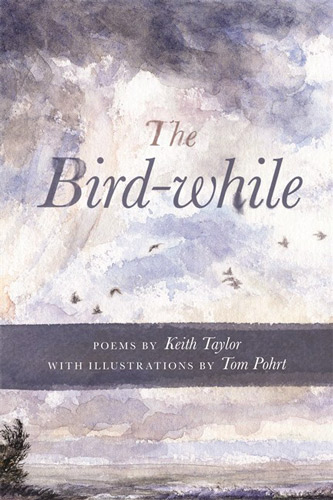

The Bird-while

Nearly 20 years ago, I was a 19-year old community college student introduced to Keith Taylor’s work via his slim volume of very short stories, Life Science and Other Stories. Since then, I have associated Taylor’s work with a special kind of mindfulness. It does seem redundant to call any poet’s work mindful, really, but his newest book The Bird-while provided me with a more precise way of defining Taylor’s attention . . .

Nearly 20 years ago, I was a 19-year old community college student introduced to Keith Taylor’s work via his slim volume of very short stories, Life Science and Other Stories. Since then, I have associated Taylor’s work with a special kind of mindfulness. It does seem redundant to call any poet’s work mindful, really, but his newest book The Bird-while provided me with a more precise way of defining Taylor’s attention, as the book is inspired by a term defined in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1838 journal:

A Bird-while. In a natural chronometer, a Bird-while may be admitted as one of the metres, since the space most of the wild birds will allow you to make your observations on them when they alight near you in the woods, is a pretty equal and familiar measure.

Here, I found poems taking risks in terms of sketching, whether focused on the current moment or a memory—poems unafraid to leave out details in a more epic grasping toward essence, and ultimately, transcendence. I found this Eastern sensibility very interesting in the first section of poems, which focused on Taylor’s travel accounts. While the cover and art within the book depicts birds and plants, it was unexpected and interesting to apply the concept of ‘a bird-while’ to fleeting moments captured in London, Copenhagen, south of Toulouse or within a poem, “After She Was Sick”:

[ . . . ] Outside the train, the night

was a moist black wall broken

only occasionally

by light from a village fire.

Since I read a good portion of the book lying on the couch on Earth Day, during the March for Science, it was a great opportunity to observe how poetry might participate in environmental politics. Taylor’s poems are never heavy-handed but use observation and facts to explore our relationship to the earth: both showcasing our problematic historical relationship and also modeling how to relate deeply in the present moment. Perhaps in a rhetorical move to mimic the ideal manner of human and nature mingling, it wasn’t until perhaps ten pages into the book that I even noticed animals or plants in the poems, and when I did, I was struck by reverence, such as in “Not the Northwest Passage”:

just the white-footed mouse, delicate

and doe-eyed, only twenty-five grams

of unrelenting passion pushing

north, a few feet for every generation

Other poems read like haikus, such as “Kingston Plains: The Ghost Forest,” which begins with prose to describe “grey stumps of white pines” then suddenly employs line breaks to wake us up:

and now,

finally,

a clump of small,

ripe

blueberries.

And perhaps not surprisingly, the most powerful section on human’s fraught relationship with nature focuses on birds, with a heartbreakingly beautiful account of rescuing a bird from an oily river and poems like “The Last Roost,” that share shocking reportage:

There’s a written record written years later:

Up in Emmet County, after months

of slaughter—50,000 a day

sent to Chicago [ . . . ]

The illustrations within the text, by Tom Pohrt, got me thinking as well. To me, the core idea at work in the book is brevity and fragility in terms of observation and composition, so I expected expressive sketching rather than dense line drawings. It would be interesting to hear more about how Taylor’s poems played into Pohrt’s work and vice versa.

As I recall in Taylor’s earlier work, he is gifted with an ability to gently reflect on the space that he occupies, whether it is in Michigan, stumbling upon coyotes in the form of “turd shaped clumps of deer fur / filled / with ragged pieces of bone” or on a road trip in “Schumann, While Driving”:

Swallows keep time

and cornfields become

scenes in Scandinavian films

I’ve never seen.

As the book crescendos in thrilling brushes with nature, Taylor does finally use the words “[ . . . ] habitat loss, / climate change and oil spills” in the very last poem, though I don’t want to spoil the ending. His essential political statement seems to be that intimate, sharply felt encounters with nature are of primary importance, perhaps precisely because nature faces such peril. My favorite lines in the book, from “The Gardener Remembers” contain this thesis and emphatically celebrates those who palpably experience nature:

[ . . . ] in spring, transplanted bloodroot, reminders

that metaphor is real and wonder

more than the condition of our loss.