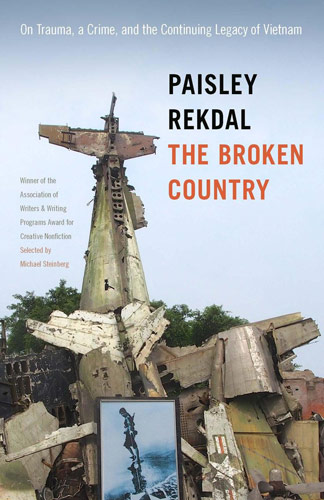

The Broken Country

Paisley Rekdal’s The Broken Country, winner of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs Award for Creative Nonfiction, grips you from the beginning, starting with a vivid description of a stabbing in a Salt Lake City parking lot, a crime perpetrated by a Vietnamese refugee. We later learn that Rekdal, who lives in Salt Lake City, just a few blocks away from the site of the crime, happened to be in Vietnam when it happened and daily visited the war memorial featured on the book cover—a sculpture created from the wreckage of wartime airplanes, tanks, and other vehicles. Gripped by the realization that the trauma of the Vietnam War still affects American culture—especially in the private communities of refugees and immigrants—Rekdal weaves together an investigation into trauma, war, and refugees that makes it impossible to forget the ongoing tragedy of wars, past and present.

Paisley Rekdal’s The Broken Country, winner of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs Award for Creative Nonfiction, grips you from the beginning, starting with a vivid description of a stabbing in a Salt Lake City parking lot, a crime perpetrated by a Vietnamese refugee. We later learn that Rekdal, who lives in Salt Lake City, just a few blocks away from the site of the crime, happened to be in Vietnam when it happened and daily visited the war memorial featured on the book cover—a sculpture created from the wreckage of wartime airplanes, tanks, and other vehicles. Gripped by the realization that the trauma of the Vietnam War still affects American culture—especially in the private communities of refugees and immigrants—Rekdal weaves together an investigation into trauma, war, and refugees that makes it impossible to forget the ongoing tragedy of wars, past and present.

The Broken Country hosts a wide cast of characters: Ly, the Vietnamese refugee who committed the violent crime; the two white men who were his victims; their families; and even Rekdal herself. But most of the stories focus on those who were not directly involved in the incident which spurred this investigation: Rekdal interviews Vietnamese refugees, many of whom, like Ly himself, were children when they were brought to America to escape the terrors of war. What Rekdal’s investigation finds is that the Vietnamese communities, and other similar ones, are filled with the stories of trauma, and that trauma is not suffered alone by the original victim. “Trauma is a broken country,” Rekdal says, “one in which the past fractures into the present, stuck like glass shards into skin, or sutured together like a tape reel from a thousand fragmented recordings.” This fracturing spills over into the children of victims, creating difficult home lives, difficulty in school, and difficulty assimilating in wider communities, which then means that the trauma of war becomes a public display, one which is sometimes violent.

The reason for these difficulties, even in second and third generations, are varied, but one of the most interesting points of Rekdal’s research is in the study of epigenetics, which has proved that the very DNA of trauma victims is changed, and that PTSD and other aftereffects of violence can, in fact, be inherited from mother to child. Perhaps because of this and many other personal and social factors, Vietnamese and other refugees from that war are far less likely than other Asian immigrants to succeed in school and are more likely to suffer from mental illness. And because a failure to assimilate is seen as a rejection of American values (even of America itself), there is perceived danger in refugees and other victims of violence.

Rekdal rightly points out that such findings can easily be misconstrued now, as the debate about refugees from Syria and other war-torn countries goes on: If it can be shown that refugees are physically affected by the war, that their very DNA makes them more prone to violence, why should we let them in to “our” country. Though the phrasing never argues it specifically, the book’s title resonates again in this argument. America is so often the cause of problems—Rekdal talks extensively about the Amerasian children left behind by troops in Vietnam—and then, when those issues come home and are brought to our attention, sometimes in violent ways, we blame the outsider, the mentally ill, and the foreigner instead of seeing our own culpability. It is our country that is broken, sometimes the source and incubator of trauma.

But like the best writers, Rekdal is not one to just blanket her accusations across the board. Instead, by making herself a character and by acknowledging the price of writing the story, she points out the complexities of telling such a story. In one section, she talks about the potential dangers of transforming stories of suffering into kitsch, a vehicle to offer the audience relief by encapsulating trauma into narrative:

As a writer, I understand that narrating anything, even trauma, relies upon using literary conventions: character and plot, heroes and villains, symbols, metaphor. We rely on stock images to engage the emotion of our listeners, understanding that these clichés may be more easily imaginable, even thrilling, than more inventive choices.

And she certainly isn’t immune to the allure of sensationalism: the book starts with the violent crime and, due to the nature of writing about trauma and war, there are several other gripping stories. But, along with the admission about writing above, Rekdal also smartly turns the gaze on the reader, who is asked to think more deeply about who commits crime and why. She admits that though most of the criminals in her book are refugees and immigrants, this is just a small slice, and that we need to expand our gaze to everyone:

We would have to admit that the problem was never a foreign contagion but one firmly rooted in all of our neighborhoods and homes. To expand our gaze to an accurate scope would be to admit the possibility that, at some fundamental and unspeakable level, each of us nurtures the seed of violence.

The force of this recognition is the strength of The Broken Country because, in a less direct way, she also gives the answer to the violent aspect of our natures: listening, compassion, and empathy. We have the choice to live in fear of those we don’t know, but we could also, like Rekdal has done in researching for this project, listen to their stories. Listening won’t give us understanding—there is no truly communicating trauma or its aftereffects—but the sharing and the listening will at least bridge some of the fissures that war creates.