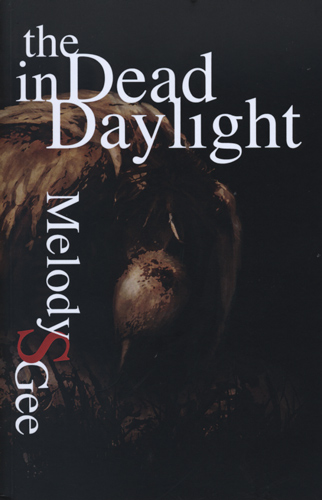

The Dead in Daylight

Melody S. Gee’s new book of poems is a compelling catalog of inheritance and family history—of trying to make a home in a world divided between incarnation and separation, life and death, past and future. The book itself is divided into two sections: “Separate Blood” and “Bone.” So not surprisingly, the poems here deal with bodies and their relation to other bodies, particularly the mother-daughter relationship, but other heritages as well.

Melody S. Gee’s new book of poems is a compelling catalog of inheritance and family history—of trying to make a home in a world divided between incarnation and separation, life and death, past and future. The book itself is divided into two sections: “Separate Blood” and “Bone.” So not surprisingly, the poems here deal with bodies and their relation to other bodies, particularly the mother-daughter relationship, but other heritages as well. The second poem in the collection, “A Womb Sound,” makes this theme (and the importance of remembering) explicit:

Don’t deny that the infant remembers:

the cut and tear that let in

the enormous light, the cut of coldair to build her separate blood.

To re-member in the face of dismemberment seems to be the struggle of Gee’s poetic project in The Dead in Daylight. She writes in “Go Back, Make Ready” that: “We know only two things: / damage and repair.” In the first section of the book, there is plenty of damage in poems with titles like “Infertility,” “A House of Paper and Gut,” and the wonderfully weird “In Us The Unused.” The latter poem is ostensibly about a leopard whose cubs all look like her, “their inheritance // whole.” However, “Inside us, inheritance is a muscle // withered to water.” The second section of the book is more a project of repair, as in the poem “Rhythms” where the poet/persona comforts her own daughter in the night by patting “a rhythm of shush on her back.”

Originality in terms of poetic “voice” (how a poet uses diction and syntax to create a poetic persona distinctly their own) is perhaps an overrated quality in a culture that largely worships individualism and novelty. Lots of blurbs on the back cover of poetry books tend to use the same phrases: “Stunning, truly original, a unique new voice” etc. But I do find Gee’s voice to be oddly unlike many other contemporary poets writing today. And I use “oddly” as a complement. Her lines are tightly and carefully constructed, but the word choices and rhythms combine to create an off kilter but incantatory quality that can become downright mesmerizing as in this excerpt from the poem “Trails”:

In famine, roads evaporate

with no one to trample them

to road anymore.

Thirst disappears a country.

Hauling rags to town, my grandmother

cannot distinguish her path

from the dismantled land.

And then this luscious imagery from the first stanza of the poem “Bat Exclusion”:

All August, our house drips

with bats’ oily bodies

slung everywhere like leather fruit.

Our house a sudden orchard.

This is a book that honestly deserves meditative rereading over time. The collection is also one of the most thematically cohesive poetry books I’ve read in a good while in terms of tone—no stray or out-of-place poems here. Rather, each poem migrates naturally into the next, creating an overall inheritance of treasures both tarnished by the past and polished with devotion. Luring the dead into the daylight has seldom been such a simultaneously uncanny and attractive experiment.