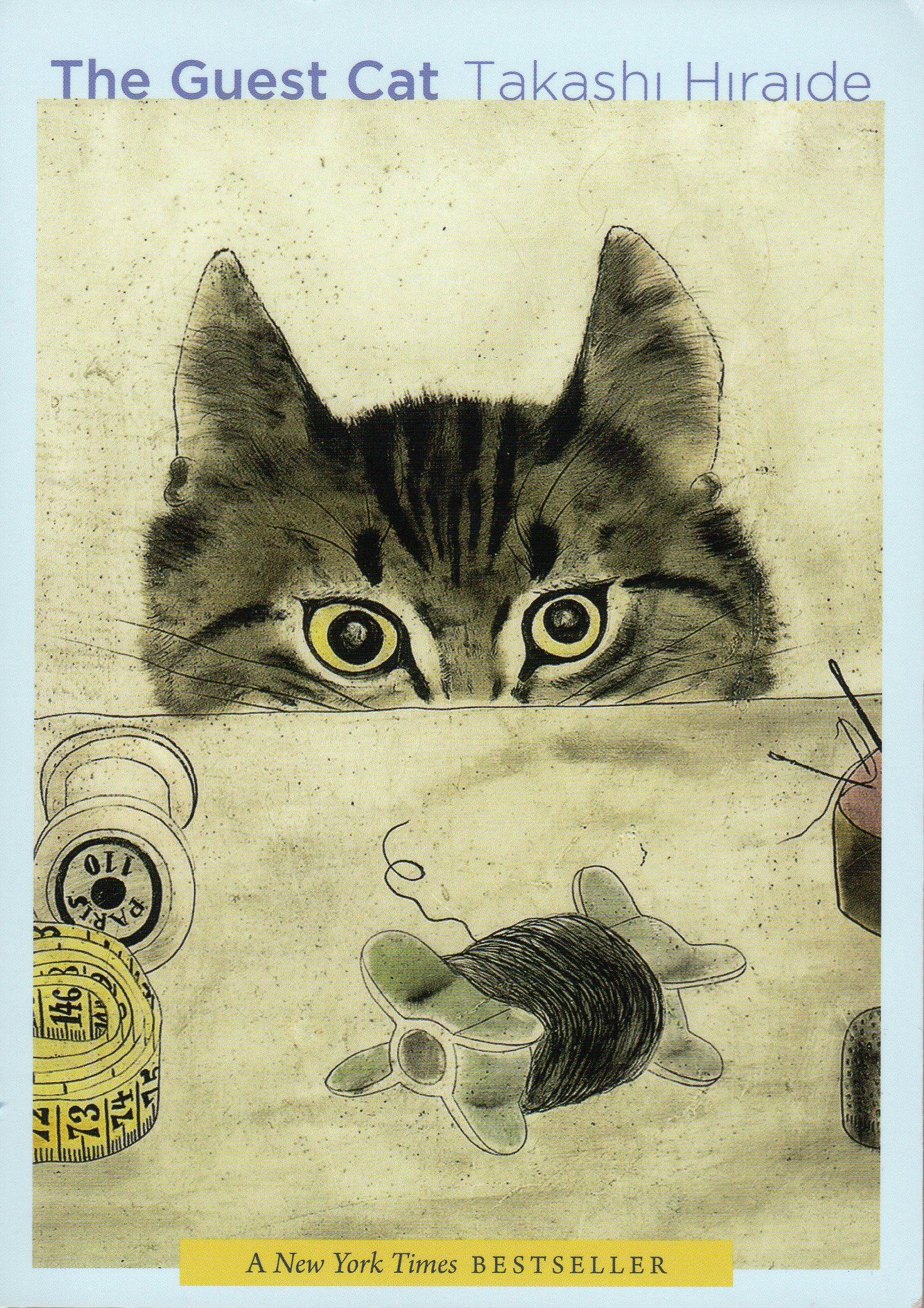

The Guest Cat

Takashi Hiraide’s The Guest Cat is nothing like the usual cat book. Takashi Hiraide is an acclaimed poet in Japan, and this novel resembles a poem, recreating the immense world in small images, opening up to life with love and loss. It’s short like a poem, but though nostalgic and moving, it is not sentimental. The end of The Guest Cat indicates this novel evolved as a reshaping of a collection of essays and journal notes about the narrator and his wife’s relationship with a neighborhood cat Chibi, meaning “little one” in Japanese. This is a quiet, reflective, even philosophical book, which can appeal to more than cat lovers, since it is about how a relationship can change a person, how a communal animal can make one question who owns the animal, and how loss can reveal not just grief but resentment. By the end of The Guest Cat, the narrator notices and loves more, even extending his love to a house he doesn’t own.

In the beginning, the narrator and his wife have a magical world where they can look out a frosted window pane and a knothole to people passing in an alleyway who seem closer than they are, and upside down. Just as theirs is a view outward from and towards a narrow space, their life is small and ordinary—both working at home editing others’ works, living in a rented guesthouse of the next door manor. Enter ordinary-looking Chibi, who opens their life with a sense of freedom, doing what she wants. The animal-loving wife explains:

What’s interesting about animals is that even though a cat may be a cat, in the end, each individual has its own character. “For me, Chibi is a friend with whom I share an understanding, and who just happens to have taken on the form of a cat.”

Inevitable change is forecast through Machiavelli’s ideas about Fortune which “dominates at least half our lives, while in the remaining half or a little less, human strength and competence attempts to counteract it.”

The couple has always known that the cat belongs to the neighbor with the five-year-old boy. Yet, Chibi making herself at home with them causes them to wonder if Chibi’s true home is with them or their neighbor. Eventually the narrator can interpret the cat owner’s resentment of their secret relationship and as the couple come out of their narrow life, they become close to the old lady owning the manor, loving the gardens and house as they loved Chibi. Hiraide briefly but beautifully charts the change of seasons, giving dates and touching upon the emperor’s death, the year supposedly ordinary, though obviously not. One day in early spring, 1987, the husband opens the windows:

The house quickly became a hollow cavity for the wind to race through…Through the slanted skylight, a few rays of sun would pierce for a moment and then vanish…everything timed to the rhythm of illumination and concealment.

After both the manor owner and the cat are gone, all the life and charm of the place vanishes, the dragonflies and even the despised praying mantis not returning.

The novel captures a cat’s behavior perfectly. Even though cats are generally mysterious, Chibi’s mystery cannot be replicated. This novel is extraordinary in showing the slow, painful regeneration after loss and the need to cling to the past until one finds their own way. This small novel covers so much. It is thoughtful and resonant and will remain with readers.