The Last Two Seconds

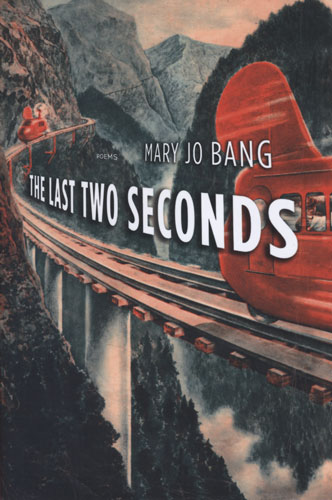

Mary Jo Bang is a slippery poet, with a mind that often seems a few seconds ahead of itself. A quick glance at the cover of her new book, The Last Two Seconds, perfectly encapsulates this kind of speed: the monorail that has just slipped from our frame of vision, the typography of the title trailing like a futurist contrail. It is this trailing, however, that is a crucial point—this collection is not about the next two seconds, but the last—as in the last two seconds you’ve just spent reading this sentence. Mary Jo Bang is a slippery poet, with a mind that often seems a few seconds ahead of itself. A quick glance at the cover of her new book, The Last Two Seconds, perfectly encapsulates this kind of speed: the monorail that has just slipped from our frame of vision, the typography of the title trailing like a futurist contrail. It is this trailing, however, that is a crucial point—this collection is not about the next two seconds, but the last—as in the last two seconds you’ve just spent reading this sentence.

Take a quick leap of scale and you land at the collection’s central concern: history. This is history as philosophy can abstract it, and it is history as the contemporary—both in a large, public sense, and a private, psychological, and immediate sense—is very much concerned with it. The monorail image is perfect—like a bullet, these poems press into the present with the weight, the momentum, of history behind them. History collapses into the singularity of the present.

But let’s leave that in the past for a moment and get to the earthquake, specifically “The Earthquake She Slept Through,” the opening poem:

In the bathroom, a large cockroach rested

On its back at the edge of the marble surround; the dead

Antennae announced the future by pointing to the silver mouth

that would later gulp the water she washed her face with.

Who wouldn’t have wished for the quick return

of last night’s sleep? The idea, she knew, was to remain awake. . .

The micro-spatial and micro-temporal sense of these lines is emblematic of a core approach Bang takes in these poems. In this case, it’s a direction of scene—these ticking cues to look at the cockroach, which deflects our gaze to the sink, which deflects our gaze into the relatively immediate future—all within the intimate context of washing up in the bathroom, and that context within the context of an aftermath, the earthquake and its subtle but pervasive hint of catastrophic transformation (read: post-9/11). It’s a ranging, but controlled, movement and layering of foci. Elsewhere, this ticking approach can be visually acute, such as in this quick development of a “silver” theme in “Sure, It’s a Little Game. You, Me Our Minds”:

A lobotomy sever between two hemispheres.

The symphony of scalpels quieted.

Peru with one cup of clean water per person.

A sliver of silver in an otherwise empty hand.

Make a landfill that looks like a mountain.

Or it can be more abstract, with an almost discursive feel, as in section two of “Let’s Say Yes: This Bell Like a Bee Stinging”:

Some concern for the half-past. Ring after ring

like something coming. It is thought,

this bell like a bee striking.

The future lies in a patter like a wood drummed.

A sensual traffic: what, where, and why.

And across the poems we tick across a variety of approaches: some poems are essayistic, others associational; some are dropped-in scenes, fragments of narrative; some feel like lectures, other’s part of a conversation, and yet others (especially the longer, sectioned poems) have a more patient, distended development. Which is to say it’s an extraordinarily difficult collection to review with concision.

But the idea of history does prevail. Bang gets into some theoretical allusion right away. In “Costumes Exchanging Glances,” we get a modified historical dialectic: “The rhinestone lights blink off and on,” as “historical events exchange glances with nothingness.” A few pages later Walter Benjamin’s angel of history reincarnates as a dog in a particularly aggressive and thought-provoking image:

[. . .] the dog

of history keeps being blown into the present—

her back to the future, her last supper simply becoming

the bowels’ dissolving memory in a heap before her.

A child pats her back and drones there there

Politics is never far behind history, and Bang has her protests: largely, against facile ideology. In “Explain the Brain” she voices it explicitly, first with the question: “Why then is fundamentalism common,” and then with the blunt and powerful closing line: “Sometimes one is wrong.” Many of these poems are political in a diverse range of ways, but their greatest successes are when politics and history reify in the material—or more specifically—the fabricated world. Bang has a fascination with made things, which orient different forces, whether in simple ways, like “the evening laid out like a beach ball gone airless” (“You Know”), or in more complex ones, as in these splendid lines from “A Structure of Repeating Units:”

I love poly socks, dishtowels with rick-rack,

a surfboard anointed with one aqua stripe.

Idle want seems to dog me along a long cord

that’s plugged into the boot in the mouth

of a near recent past.

Loosened up a bit, the notion of fabrication extends in these poems into the territory of art—ekphrasis being one of Bang’s hallmark domains—and, I’d like to argue, psychology. In a way, psychology is fabricated by the events of history—both personal and public—into a kind of material. It is within the exploration of this force that these poems reach their highest emotional tenor.

The title poem provides readers with an example of this heightened emotional tenor at the nexus of history and psychology. In this, Bang seems to locate us within the mind of a woman in a hospital bed:

[. . .] Outside,

Rain at the window created an instant vertical sea.

The land looked like beached long-nose dolphins

stunned into immobility. Light blinked intermittently

in the haze. She looked back blankly and said, the mind

isn’t everything, only a gray-suited troop of mechanics

working to ratchet the self through the teeth of a wheel.

There is a lot to explore in this collection, and many entryways, but I hope to have provided enough of an overview of the concerns, variety, and craft on exhibit to motivate readers to want to enter into their own exploration of Bang’s work.