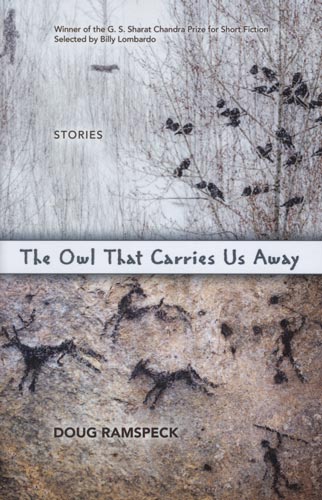

The Owl That Carries Us Away

When I think of fiction, I imagine literature that takes me far away from my own reality into other worlds. Anticipating Doug Ramspeck’s first fiction book The Owl That Carries Us Away, I almost envisioned a giant owl taking me to a brand-new world. To my surprise, however, I found myself, or rather lost myself, in worlds similar to my own. The familiar places and situations opened possibilities for me to relate to the characters and sympathize with them, while the carefully crafted language became the link offering connections to the author’s worlds.

When I think of fiction, I imagine literature that takes me far away from my own reality into other worlds. Anticipating Doug Ramspeck’s first fiction book The Owl That Carries Us Away, I almost envisioned a giant owl taking me to a brand-new world. To my surprise, however, I found myself, or rather lost myself, in worlds similar to my own. The familiar places and situations opened possibilities for me to relate to the characters and sympathize with them, while the carefully crafted language became the link offering connections to the author’s worlds.

“The boy is washing the possum skull with his mother’s hose.” Simple, yet strange, Ramspeck’s prose is gripping from the very first sentence. Here is a little more from the titular first story:

He found it in the mud beside the river. It was half-buried and stubborn, even when he poked it with a stick, even when he tried to pry it free with his fingers. Now he cleans the dirt out of the sockets with the spray of the hose. Pours the water through the teeth. Watches the water sliding across the pale bone. Hears the water splashing against the stone steps.

Ramspeck brings his readers into direct involvement with a curious object, the skull of an opossum, that was found by a boy. In addition to the skull, the author introduces a few other omens that loom over characters throughout the short story:

The light snow that is falling is bone colored, too, as though the great skeleton of sky has broken into shards and is coming down, falling out of the fat and low-slung clouds, and the boy carries the skull through the kitchen door, hiding it behind his back. Something is frying on the stove, lifting smoke, sizzling a complaint, but his mother isn’t there to tend to it. The room has been left by itself, the glasses and plates abandoned on the kitchen table.

With heavy clouds, discolored snow, and empty rooms, Ramspeck sets the dark mood for the story that nudges readers to sympathize with the boy as he goes through traumatic experience.

Ramspeck’s story “Omphalotus Olearius” traces a young woman’s change in her attitude toward her new husband. Titled after a poisonous mushroom commonly known as the jack-o’-lantern mushroom, this story illustrates the young woman’s obsession with the mushroom:

They are growing wild from the earth, multiplying. They appear disfigured, somehow, like hideous flowers, dead growths that rise into the air. She finds the sight of them unsettling, disturbing, and thoughts of them keep returning to her mind during her lunch shift at work. She is so distracted that she drops an order of wings with barbeque sauce into the lap of one of her favorite customers. She is so distracted that she doesn’t see a squirrel until the final moment as she is driving home.

She cannot go about her day until she destroys the mushrooms. After “chop[ping] at the heads of the mushrooms,” the young woman starts noticing things about her husband that she didn’t see before. While the story is only three pages, Ramspeck manages to transfer the young woman’s feeling to his readers, and, what fascinates me the most about the story, he does it by using language in subtle yet powerful ways.

Written from the first point of view, “Spring Snow” offers a man’s story about his father and his relationship with him. This recollection of the past provides a glimpse into the life of a boy, Frankie, whose father’s irrational beliefs destroyed his family. Ramspeck sets the scene by illustrating these beliefs:

It was my father who believed he could read into the world its future, who told me often in childhood that three crows in a willow tree were the worst omen, portending the death of a loved one, a serious illness of a neighbor, or a miscarriage for a cousin. He seemed to think there was a hidden numerology in nature, and often I saw him counting blue-jay feathers left without warning on the grass, or tallying blood drops dotting the snow come winter, or lining up pairs of dead frogs floating in the shallows of the river beyond the barn.

The title of the story becomes clear when the narrator explains how these beliefs combined with his father’s drunkenness and mood swings are illogical and “contradictory as spring snow.” With frequent arguments and drunk parents, Frankie’s home life could not be called happy.

Doug Ramspeck’s The Owl That Carries Us Away offers twenty-nine stories that deal with disappointments, childhood traumas, and tragedies, among other themes. The author presents his worlds in ways that often don’t outline the why’s in neat little bows. Instead, the stories present themes and ideas that demand their readers to feel emotions. The Owl That Carries Us Away is a collection of stories that will leave no one unmoved.