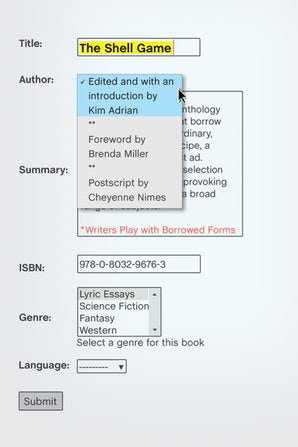

The Shell Game

If you are looking for a book that fits into the genre of “Creative Nonfiction,” especially as an introduction, your best bet is to pick up The Shell Game immediately, edited by writer Kim Adrian. It is an anthology of lyric essays that range from crossword puzzles about becoming a grandmother, to eBay ads for the writer himself (0 bids, Price = $9.95).

If you are looking for a book that fits into the genre of “Creative Nonfiction,” especially as an introduction, your best bet is to pick up The Shell Game immediately, edited by writer Kim Adrian. It is an anthology of lyric essays that range from crossword puzzles about becoming a grandmother, to eBay ads for the writer himself (0 bids, Price = $9.95).

The title is a play on the “hermit crab essay,” a term coined by Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola in the January 2015 issue of Brevity. In “The Shared Space Between Reader and Writer: A Case Study1,” Miller describes hermit crab essays as those that:

adopt already existing forms as the container for the writing at hand, such as the essay in the form of a “to-do” list, or a field guide, or a recipe. Hermit crabs are creatures born without their own shells to protect them; they need to find empty shells to inhabit . . .

In other words, they are stories too fragile, too raw and beautiful for the world, unless tucked away.

The anthology includes an excerpt from Jenny Boully’s The Body, which epitomizes this idea of the hermit crab essay by discussing a love affair (and so much more) but being entirely written in the form of footnotes. By doing so, Boully provides the reader with mere glimpses and offbeat details of a story significantly larger, a story almost too complex for words. However, at the same time, the footnotes-as-the-story sort of belittle the overall, seemingly missing play-by-play account, turning Goliath into David and vice versa.

“Questionnaire for My Grandfather” by Kim Adrian starts:

Please answer all questions as simply as possible; do not use digression as a means of evasion. Feel free, however, to elaborate on the point at hand to a reasonable degree so as to provide the clearest and most informative answer you can.

The first few questions of the survey are rather straightforward (“Is it true, as family legend states, that you ran away from home at the age of thirteen?”), but as the essay continues, the questions become uncomfortable, to say the least (“True or False? You sexually molested all four of your daughters.”). When you think it can’t get any darker, it does, but the questionnaire “shell” helps the reader digest such heavy material.

With that being said, though, sometimes, instead of the story hiding behind its shell, the shell disappears behind the story. Neither is better or worse than the other, but the mind does this strange, epiphanic click when it catches itself following narrative as opposed to form. For example, one of my favorite essays in the collection is Ingrid Jendrzejewski’s “#miscarriage.exe.” The essay is written as computer code:

#8:00 am

drive(daughter,preschool) hug(daughter) kiss(daughter) return(home)

subroutine toilet ()

Subroutine cry ()

Subroutine pain_management(time).

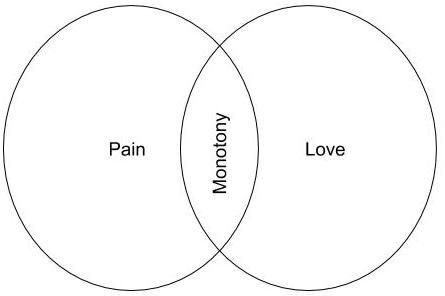

In the beginning, reading the essay feels like a task, but after a few pages, the shell starts to fall off and you almost forget about it. It makes me think of George Saunders’s “The Semplica-Girl Diaries,” but stripped of its comedic “shell,” and only bearing the harsh truths of pain, love, and monotony—which are essentially one in the same, or something like this, if we’re borrowing from the creative format of the anthology:

Some of the other essays include rejection letters, multiple-choice quizzes, police reports, trivia cards, instruction manuals, and Harvard Outlines. The Shell Game pushes the boundaries of prose and opens up a whole new world for what is considered “acceptable.”

In the Postscript written by Cheyenne Nimes, there are 400-some possible choices of “shells” that one could use to cover their own personal hermit crabs: Divorce papers, grant application, teaching philosophy, notes from a stakeout, surveillance report, party invite, thank-you note, legend to an old or new map, GPS directions, witches’ spell/brew, contract, weather report, FAA black box recording transcript, advice column, resume, to name a few. After going through all of them, it’s hard to imagine any other methods of sculpting an essay, but I think that was almost the goal of Nimes’s Postscript: to challenge the reader/writer to keep the list going, borrow forms, and produce work that one wouldn’t usually think of.

This book is the science fiction of creative nonfiction, or better yet, the Ulysses of the modern essay. It’s a shell for itself, in that, without claiming these essays as “essays,” one wouldn’t know what to call them, what to do with them. The Shell Game is far from the five paragraphs that grammar schools teach, and it makes readers feel as if they are learning what an essay is (or could be) all over again.