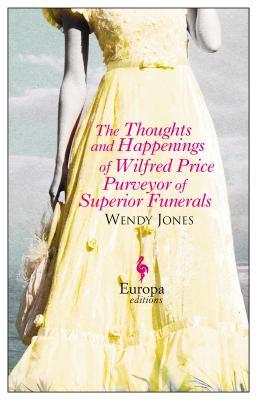

The Thoughts and Happenings of Wilfred Price Purveyor of Superior Funerals

The title of this debut novel by Wendy Jones, The Thoughts and Happenings of Wilfred Price Purveyor of Superior Funerals, suggests a fun, light, old-fashioned read, which it partly is. But it also deals with serious, timeless subjects, though the resolution reflects the time wherein the novel takes place: 1924, in the small Welsh town of Narberth. At first everything seems idyllic. Wilfred Price is enchanted by Grace Reece in her yellow dress. While they are enjoying a picnic, Wilfred proposes to Grace. Almost immediately, he realizes he does not love her, but she has responded, “That would be delightful.” Thus, the town considers the two engaged. Wilfred goes in vain to correct the situation at Dr. Reece’s surgery, and he resorts to telling Grace on the street that he doesn’t want to marry her. That is the beginning of causing hurt—the novel’s most consistent theme.

Meanwhile Wilfred has met Flora during the funeral of her beloved father. Wilfred himself has a loving father, a widower since Wilfred’s mother died in childbirth. And with Wilfred being the town’s only funeral director and his father a gravedigger, they are not in the Reeces’ same social class.

Grace also has a horrible secret, rape resulting in pregnancy, which she finally has to disclose to her father. The result is that Wilfred, assumed to be responsible, is forced to marry Grace. It is then that another difference between the two families emerges—the unhappy marriage of the Reeces vs. Mr. Price, Wilfred’s father, still loving his dead wife. Both Wilfred and Grace are innocents, caught and imprisoned in a marriage with the potential to become like that of the Reeces. Wilfred does not dare to go against the powerful doctor, his father-in-law, because such rebellion would result in no funeral business and no money to support his old father.

The novel’s expected sweetness comes out in the young people’s innocence, especially Wilfred’s in his love for Flora and his naiveté about women and wives. His funeral apprenticeship, guided by a Mr. Ogmore Auden who warns against “lustful thoughts,” is devoid of practical advice:

He knew he wanted a good woman but beyond that Wilfred wasn’t at all sure what made a good wife. . . Wilfred didn’t know what marriage involved. Because his father was widowed, Wilfred had had no insight into the day-to-day goings-on of marriage, hadn’t grown up enveloped in one. He imagined the worst ones were like Punch and Judy’s marriage. . . the man hit the woman, the woman nagged the man, and they lived with an alligator.

Another amusing aspect of Wilfred is his love of words: “Superior sounded honorable, although he could hardly advertise himself as Purveyor of Inferior Funerals. What would that mean? Burying the living? Dropping the body?” He’d bought a dictionary and picked out one word a day to learn. He started using the words, knowing their uselessness in his predicament. How would avocado help him? And his father reflected:

He wanted to ‘augment’ the funeral business with a wallpaper shop…Well, there wasn’t much augmenting going on for Wilfred now, whatever augmenting was.

The reader does learn some potentially disturbing details about how the funeral director prepares the body, but Wilfred’s problems stand out more:

Why didn’t people listen to one another? Wilfred thought hotly. Why didn’t they just listen! If people could explain themselves, there could be understanding. But no, some people—quite a lot of people even—were bullies. They wanted other people to do what they wanted them to do, and if they had power, like Dr. Reece did, then sometimes they used that power, bossed people around and messed up their lives.

The reader may be disturbed by the resolution to Grace’s problem, so different from how it would be handled today. But the reader will delight in Jones’s creation of a well-plotted page-turner, the charm of capturing Wales and its language, and particularly in her fulfillment of the sweet, old-fashioned promise of the novel’s title at the end.