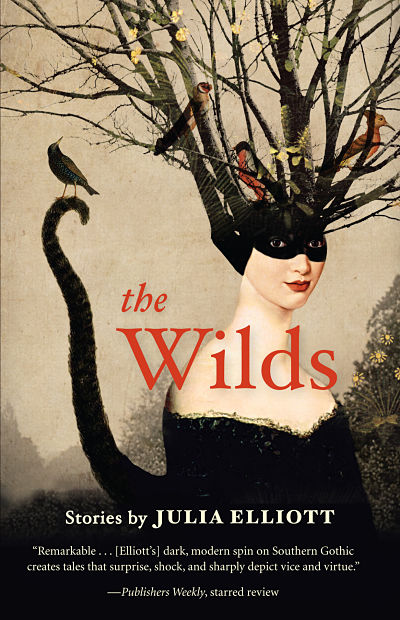

The Wilds

Flipping a page in Julia Elliott’s short story collection The Wilds is opening a page upon whole new futuristic worlds that do not stray that far from our own. On one page you’ll enter a spa for “bodily restoration” with goat-milk-and-basil soaks, kelp baths, and lunches of raw vegetables and fermented organ meats. Turn the page and you’ll enter a scientist’s lab where a sexless robot falls in love. Further in still, you’ll discover a disease that feeds on teenagers, causing them to obsess over videogames or social-networking sites and to have a social withdrawal and “a voracious appetite for junk food.”

Flipping a page in Julia Elliott’s short story collection The Wilds is opening a page upon whole new futuristic worlds that do not stray that far from our own. On one page you’ll enter a spa for “bodily restoration” with goat-milk-and-basil soaks, kelp baths, and lunches of raw vegetables and fermented organ meats. Turn the page and you’ll enter a scientist’s lab where a sexless robot falls in love. Further in still, you’ll discover a disease that feeds on teenagers, causing them to obsess over videogames or social-networking sites and to have a social withdrawal and “a voracious appetite for junk food.”

Though you won’t totally feel at home inside, you’ll pick up on the stark social commentary and comparisons to our own world. Often using dystopian and fantasy elements, Elliott’s writing is imaginative, her characters are often strange, and the whole collection is a dark treat you simply can’t put down.

I was immediately engaged with the first story, “The Whipping.” It begins, “In one hour and forty-five minutes my punishment will transpire. That’s how Dad, who sits in the kitchen flicking ash on his greasy plate of pork crumbs, always says it.” But the narrator has a plan, “The best way to delay a whipping is to keep my parents angry. They won’t whip us when they’re mad. That would be abusive.” She, starting to mature, acts out against her parents’ punishments and rules and sneaks their old cigarette butts. In fact, it may seem like a fairly normal tale if it weren’t for her father picking apart the robin that her twin brothers killed: “They might be frogs or mice or fatty little moles. He rolls the dead things in flour and drops them one by one into the spitting skillet . . . ‘Delicious,’ he says, bathing us in the glow of his ghoulish grin.”

The title story is probably one of my favorites as it entices the inner child in me. Told from the point of view of a pre-pubescent girl, “The Wilds” steps inside the narrator’s neighbors’ lives, seeming mystical and enchanting:

We were deep into summer and you could see the vines growing, winding around branches, sprouting bumps and barnacles and woody boils that would fester until they could stand it no more, then break out into red and purple. It was night and the Wild boys hooted in their shrubbery. They wore dirty cutoff jeans. They carried knives and BB guns and homemade bombs. I could smell their weird metallic sweat drifting on a breeze that rustled through the honeysuckle. The Wild boys had dug tunnels under the ground . . . They whirred from tree to tree on zip lines and hopped from attic windows out in the bustling night.

At the beginning, it almost feels like Neverland, but once the narrator and reader are led into The Wilds’s house, we discover that something much darker is at play: the moon turns Ben into the wolfman, pus-filled pimples covering his skin. I won’t go further with it than that, but it is certainly a dark take on the coming of age tale.

In the final tale, Possum, Tim, and Lisa head out to Bill’s remote shack to convince him of a reunion for the show Loser Bands of the Nineties. In it, Tim and Possum play a back and forth game predicting what they would do in certain situations at the end of the world. Lisa is busy remembering and reliving her past romantic relationship with Bill. And while they head home with Bill’s commitment to show up to shoot the video, they don’t really know what the future holds or how it will change.

It seems that throughout, as we get closer to the “end” of the book, the stories become more and more focused on the end of the world (which, by the way, the last story is so appropriately titled). But I feel I should point out that Elliott doesn’t go so far as to give you an end, to any of her stories really. They wrap up, in a way, but there isn’t much of a resolution, seeming as if these stories carry on beyond the confines of the pages. The end of the collection alludes to the future being “a mess of construction cones,” perhaps a hope for our own world to make a change, so that hopefully we don’t turn out like some of the worlds in Elliott’s writings.