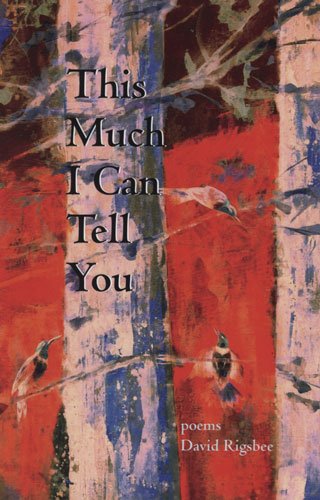

This Much I Can Tell You

Winner of two NEA fellowships, a Pushcart Prize, and an award from the Academy of American Poets, David Rigsbee is a seasoned American poet who has published ten books of poetry, multiple chapbooks, and a few translations over the past forty years. The poems in Rigsbee’s newest collection, This Much I Can Tell You, are as circumspect in language as they are in dispensing an immediate and experiential wisdom, as the book’s title implies.

Winner of two NEA fellowships, a Pushcart Prize, and an award from the Academy of American Poets, David Rigsbee is a seasoned American poet who has published ten books of poetry, multiple chapbooks, and a few translations over the past forty years. The poems in Rigsbee’s newest collection, This Much I Can Tell You, are as circumspect in language as they are in dispensing an immediate and experiential wisdom, as the book’s title implies.

An ominous first poem, “January” is a lyrical stroll through a landscape of Greek ruins. Opening on a note of irony and an allusion to Hades, the speaker begins, “Being a man, I was least / among the shades,” a statement that serves as both a physical description of the speaker’s shadow and his sense of triviality among these legendary dead. Next, the speaker studies the crumbling caryatids who seem so distant and “ornamental, / no longer load bearing” compared to his present moment.

As the speaker notes the sun “sinking toward the rim” of the horizon, he decides to follow the advice of the old poet who advised the living “to walk across a field” rather than “revisit the sorrows” at a moment like this. This advice seems to set the tone for a book of embodied wisdom—a book of personal experience and reveries instead of more distant reflections. “January,” the poem’s title and setting, is both a bleak wintry month and the beginning of a new calendar year, and in some Dantean sense, this poem seems to mark the dark lyrical start of this midlife collection.

Rigsbee’s other poems in This Much I Can Tell You also tend to be short, single-stanza lyrics with winding sentences, spare selection of detail, Americana images, and meandering chains of personal association. Poems like “Armature” are pleasantly focused and understated reveries, while a poem like “A Certain Person” is much more jarring for its complex sentences, multiple negations, and quickly shifting topics—from Auden, to a plaque, to a park, to the homeless, to Artie Shaw and Lil Wayne, to a mouse drowning in a sink. Finding a common thread or theme is difficult. Poems like this feel much more privately significant than publicly accessible, more like the poet turning to us and saying, “Sorry. You had to be there.”

Personal association seems to be the arrangement principle for this collection, where poems jump around in time and place from the 1960s to the present moment. The poem “A Breakfast” and “The Earwig,” for example, are arranged right next to each other, and both happen to share the sighting of an earwig—a detail oddly particular enough to suggest their associative link. Most other poems in the book are less apparently related to each other, except that they share a common speaker and similar patchwork of themes.

One of the more tender, direct, and accessible poems in the middle of This Much I Can Tell You is “Out of the Past,” where the speaker and his wife watch Anderson Cooper and The West Wing together. The memory is both mundane and intimate, and the speaker admits it is a scene from “a banal marriage.” The wife puts her leg over her husband’s, and he eventually starts to massage her foot, likening the rhythmic motion to a song “in which all you ever meant / and all you desire are folded in / an artless verse.”

Kind as the gesture seems, the passion between these two has already cooled, and the speaker compares his act to a love song recorded by someone “remembering love, not living / in its company.” At the poignant ending of the poem, the speaker describes the beloved’s feet as “ready” for other places: “When I put them / down, they pointed away.” There is little trace of accusation or bitterness in this understated little poem—it is just a representative memory of a failed relationship with its own quiet melancholy. Careful balances like these are a mainstay of Rigsbee’s more accessible poems.

The final poem in this collection, “Not the Mighty but the Weak,” is a haunting reflection of an old dying man in the personal library of his house. The man knows “the condition and pitch of each soul” speaking through the books on his shelf—of Emerson and Pierce—better than his own soul, which once advanced and now retreats into memories.

On the brink of death, this old man considers the tedious and circuitous range of thought represented in his many books: “the unremitting fury of the leaves, / the yawing of the shelves where he paced, / and sheets of dust.” At the end of the poem, the natural images used to describe the estate in the beginning of the poem become emblematic of the world of ideas within his books. “Leaves” now take on the sense of written pages and the “stream” outside the man’s house seems to represent the mysterious life force:

The stream felt

them [the books] too, and took them briefly in

before taking them altogether, as if

completion was a subject fit for a library

whose freshest word murmured anxiously,

on and on, from an impossible distance.

As the man awaits death, he cannot make sense of these different voices from his shelves. Collectively, they are a “freshest word”—a stream whose flow is continuous, though its source is distant and mysterious. These are the limits of human experience, and the “this much” from This Much I Can Tell You.

David Rigsbee’s This Much I Can Tell You is a moving collection with a speaker who probes the limits of experience and the trends of American life. The poems in this collection are as gracious and humane as they are critical and introspective—a balance sorely needed in these times.