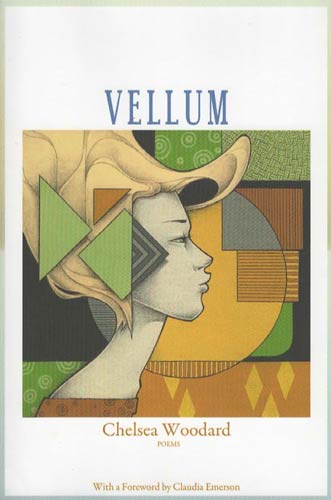

Vellum

Chelsea Woodard’s poetry collection Vellum was a finalist for the 2013 Able Muse Book Award, judged anonymously by the Able Muse Contest Committee. The forty-six poems are well-balanced with nine to ten poems in each of the five parts, though not grouped by specific theme or setting. Chelsea Woodard’s poetry collection Vellum was a finalist for the 2013 Able Muse Book Award, judged anonymously by the Able Muse Contest Committee. The forty-six poems are well-balanced with nine to ten poems in each of the five parts, though not grouped by specific theme or setting. Some of the magazines the poems previously appeared include: Blackbird, Southwest Review, and Birmingham Poetry Review. Woodard is also included in Measure, an international journal of formal poetry publishing poems of form and meter. Vellum is her first poetry collection.

Before reading the book, I wondered about the title, Vellum. I knew the term in reference to medieval manuscripts and now believe the title was used because of Woodard’s affinity for historical themes, reflections, seeing the past, and—perhaps like the mythical Philomela—capturing the truth for others to see through craft. The last poem in the collection, “Philomela,” is based on a woman in Greek mythology who was raped and had her tongue cut out by her sister’s husband. She wove a tapestry telling what happened. Woodard’s “Philomela” shouts the imposed silence of the waiting woman locked up sewing her revenge. Matthew Arnold (1822-1888) also wrote a famous poem with the same title. Philomela captured truth on tapestry; Woodard works with words that surely will also last.

The shortest poem in the collection “Uterine Vellum” notes: “this calf carries the gestations of strangers: / unburdenings inked into words. . . .” Tapestry is in the poem “Unicorn,” in which the mythical animal is called female, “stitched into wool and silk,” and is sought in “cellar-dark exhibit halls that trap her form.” Later in the collection, the “Girl Worker at the Ponemah Mills, Taftsville, CT” is about a girl “Centered behind / white lines of spools, her downturned focus mines / the spinning mule’s drone for something out of reach.” On topic with capturing through craft, paintings are a repeating subject of such poems as “Hudson River School,” “Self-portrait at the Allegory of Painting,” “Still Life” and others.

The first impression of her poems is their youthfulness—girlhood impressions that are fresh and true like confessions of being jealous of a girl admired by others for her looks. The longing for transformation rings true, as does escaping like mythical Pegasus, being lifted from a local library book, ”hauled skyward” as in the poem aptly named “Pegasus.” Perhaps also wishing some “deathless, disembodied flight” (“Craftsman”) as well as a consciousness of “tower-locked daughters” (“Unicorn”). The topic of fortune telling such as “Pravda” the longest poem in the collection, and “Tarot” also touch upon a similar youthfulness.

Woodard is familiar with being out of doors, as seen in the details in “Mushroom Hunter.” Some of her poems show close observation of birds such as purple finches, swans, or in “Indian Summer,” herons:

Shamed out of doors by sudden heat,

aflare, scorching the living room’s

tall windows to the south, I quit

the house for the woods, for long, measureless

walks past oak leaves hanging face-level

on spider threads, past the fall-littered

pond the heron stalks, restless[. . .]

“Aubade” is a poem about early morning, the dawn, in which Woodard compares the struggle of awaking from bad dreams to elements of nature. The title is a traditional term for a form is adapted from French and Latin.

“The vision of harmony is the theme of poetry,” an observation of English writer, John Galsworthy, certainly applies to this American poet. Woodard’s lines have balance, structure, and beg to be read again. They are unpretentious and even if often using classical subjects, do not hold readers at a distance, but regard them like trusted, close friends. It has been an honor to review this collection of a young poet writing in a formal style with such skill and disciplined craftsmanship when the majority of poetry written today is free verse. May this first collection be followed by others also in the challenging formal style requiring a special kind of poet and publisher—and equally discerning, appreciative readers.